Traditional leaders assign land giving little consideration to spatial planning for long-term, sustainable settlement. People are settled in places unsuitable for human habitation. And climate change will bring added volatility and exposure.

At the funeral of five members of a family who were crushed to death by their collapsing house a few weeks ago, KwaZulu-Natal Premier Sihle Zikalala spoke about land ownership. He rightly pointed out that people have settled in disaster-prone places because they don’t have land. Vast amounts of land in South Africa continue to be held by a few.

The disaster must be a catalyst for us, as a country, to address this issue seriously. The land expropriation question — that we hear little about nowadays — must be put firmly back on the table to address the dire hunger for well-located land relative to livelihood opportunities.

Additionally, there are two issues that the floods and accompanying destruction and deaths have flagged — the role of traditional authorities in where and how people settle, and the quality of houses being built in rural and peri-urban areas.

There is a serious problem with how land allocation is taking place. Traditional leaders assign land giving little consideration to spatial planning for long-term, sustainable settlement. In many areas, people are settled in places unsuitable for human habitation — too close to river banks or on slopes that will become unstable over time due to building excavations. On top of that, climate change will bring added volatility and exposure.

Some traditional authorities ask people to pay extortionate amounts to be allocated land. And residents and land seekers support this dangerous practice because their land hunger overrides any reflection on long-term consequences.

We have a wall-to-wall local government system in this country where municipalities are responsible for spatial planning for human settlement, providing infrastructure and other related functions. Yet traditional authorities and communities push back fiercely when municipalities try to intervene in land allocation where they have the capacity and competence to do so.

In many instances, municipalities simply do not have adequate planners and other built environment professionals to undertake the work at the scale required. Where they do, they run up against people who refuse to be told by some “child who is not even from that area” what to do on their ancestors’ land.

A consequence is that we have many more disasters waiting to happen. People have built up unplanned settlements, many of which, in time, will not withstand adverse weather events.

In these poorly planned rural settlements, there is little to no quality control of the houses being built. I have spent the last weeks travelling in different parts of KwaZulu-Natal. Even within designated townships, let alone rural villages, much construction happens without any involvement of municipal inspectors. There is simply no quality assurance of the structures being built, no set standards, little compliance with existing rules and barely any enforcement.

Historical problems around who holds what land have led to impoverished communities living on the unsuitable land that Zikalala talked about. In colonial times, people were forced to live on dangerous terrain as their land was taken away. Yet the state is compounding the problem by failing to redistribute land in meaningful ways — and since 1994, it has let things go from terrible to disastrous for the future.

Rather than reining in traditional authorities and resolving the relationship between them and municipalities in the long-term interest of the people of South Africa, the State has let things get out of hand. I don’t see how the country will even begin to develop proper spatial planning in rural and peri-urban areas without having to relocate millions of people. There will be massive resistance to any attempt at such relocation.

It is very attractive to live in a village on the outskirts of a town where you don’t have to pay rates and taxes like townspeople do. We have thus seen the exponential growth of settlements of this nature over the last decade or so.

This will have serious consequences when adverse weather events take place — houses will collapse, people will lose their possessions and it will be difficult for rescuers to access places that do not even have planned roads.

We need to talk about the role of traditional authorities and how they have carved out a dangerous role for themselves in relation to municipal functions in the country. We also need to talk about the dearth of skills, capacity and even interest in doing proper planning by municipalities in rural and peri-urban areas.

We are sitting on ticking time bombs in South Africa. When they detonate from time to time, many lives will be lost. This was all so avoidable two decades ago. DM

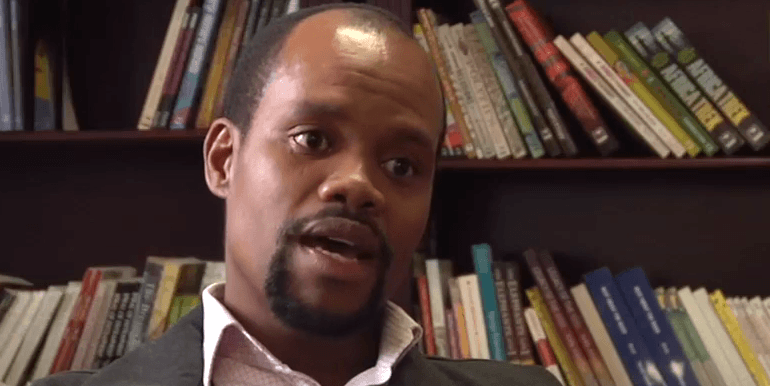

Dr Mbongiseni Buthelezi is the Executive Director of the Public Affairs Research Institute (Pari) at the University of the Witwatersrand