This commentary was written by Anna Malindog-Uy for the ASEAN Post and selected as one of the top stories of 2020

Main photo: this file photo shows an armed Malaysian policeman manning a security checkpoint in Lahad Datu, Sabah. (AFP Photo)

Matters related to territorial disputes both land and maritime, particularly in the case of Southeast Asia (SEA), are among the most contentious issues in the region’s politics nowadays. These territorial disputes did not materialise indigenously and organically on their own accord but were products of colonialism.

One must remember that the borders and frontiers of Southeast Asia were not determined by locals, but rather were prescribed by former colonial rulers and drawn up far away in European capitals. Through treaties and agreements, lines were drawn on maps, producing “unnatural boundaries,” which cut across ethnic, religious and even linguistic groups or areas, without the actual physical demarcation through survey and physical marking. This makes many borders and boundaries in Southeast Asian states nebulous and ambiguous.

This has resulted in contentious territorial claims, redefinitions of borders, the quest for the recovery of "lost territories," and even secessionist movements right after the retreat and withdrawal of colonial powers from the region. Thus, the newly independent states after World War II have inherited national borders based on colonial maps, which some parties to this day, refuse to accept.

Ill-Fated Bilateral Relations

Two Southeast Asian states tormented by these territorial problems are the Philippines and Malaysia.

Having been colonised for hundreds of years, the Philippines and Malaysia are heirs to the territorial arrangements of their previous colonial masters. Hence, it seems that Philippine-Malaysia bilateral relations from the very beginning was somewhat ill-fated and for the most part problematic because both countries are embroiled in issues of territorial disputes – land and maritime.

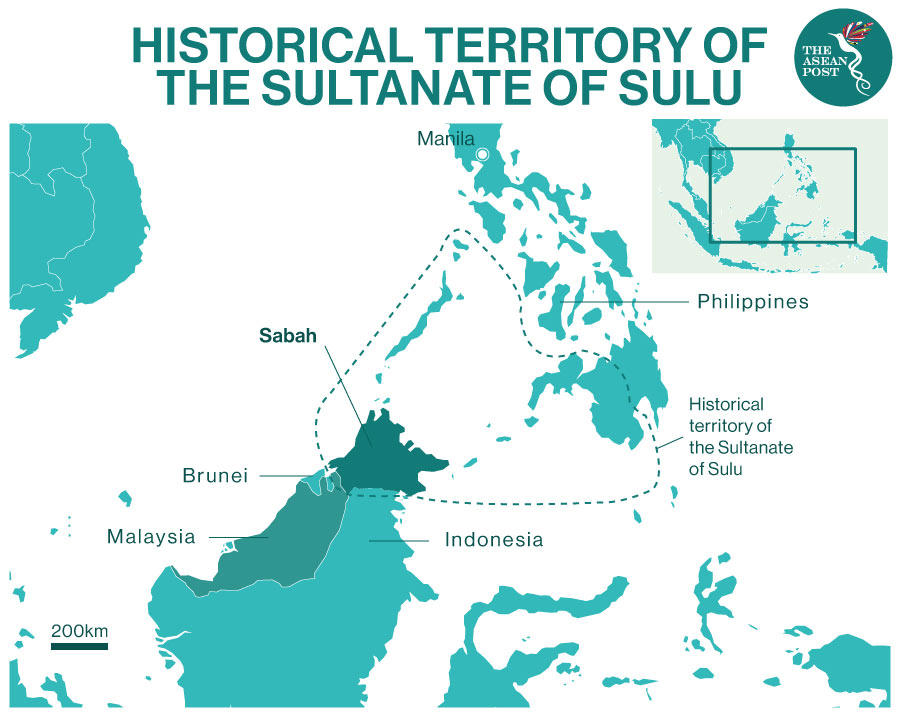

Both countries are claimants to the disputed waters of the South China Sea, and both have competing claims over Sabah or also known as North Borneo.

The Philippines was colonised by Spain for almost 400 years, and then of the United States (US) for almost half a century. Whereas Malaysia or previously known as the “Malay Peninsula” was first colonised by the Portuguese with the capture of Malacca in 1511, then followed by the Dutch in 1641. But it was Great Britain after initially establishing bases at Jesselton, Kuching, Penang, and Singapore, that ultimately secured their hegemony across the territory that is now modern Malaysia.

Even though relatively dormant and playing second string to the South China Sea disputes in recent years, the “Sabah Dispute” has always been a major thorn in the bilateral relations of the Philippines and Malaysia.

The Sabah Dispute stands out vis-à-vis the competing claims of both countries not only because it involves a large tract of land, but more importantly because it is populated. Thus, historical and legal considerations are not the only factors that are of significance in the settlement of this territorial dispute, but the right to “self-determination” of the inhabitants of Sabah is also a major consideration.

And this makes the age-old territorial dispute over Sabah more sensitive precisely because it involves not only the economic, strategic, maritime, and security considerations of the claims of the Philippines and Malaysia over the disputed territory, but also the determination of the fate of the people living in Sabah. This as well involves the fate of thousands of Filipino refugees, migrants, and their descendants in Sabah that remains in limbo until today.

The Sabah Dispute involves people living in the territory whose right to self-determination must be respected.

To note, “self-determination” is the embodiment of independence and freedom of people to define who they are as a nation and what constitutes their identity as a collective. It is also the inherent rights of people to define the tone and tenor of their destiny as a people in consonance with their beliefs, traditions, customs, and culture in general, without being suppressed, constrained or dictated by any external forces, or governments, or by another state.

Economic And Security Factors

The Sabah Dispute aside from the fact that it is a product of colonial configurations and whereabouts is also anchored in economic and security considerations.

The Philippines' claims to Sabah are not necessarily limited to economic motivation and the expression of Filipino pride and nationalism rather is much more than that.

Since, the time of President Diosdado Macapagal (under his administration the official claim to Sabah was filed in June 1962), one of the most important rationales behind the Philippines claims to Sabah was because of security concerns. During Macapagal’s time, the spread and expansion of communism into the southern backdoor of the country was identified as a key security concern.

This has been evidenced by the long letter of Macapagal to the late President Kennedy on 20 April, 1963 where he said: "North Borneo (Sabah) as part of the Philippine territory is vital to the security of the Philippines. The Philippines is like an inverted bottle with the Sulu Sea as its open end in the south and to which North Borneo is the cork. North Borneo is only 18 miles from the nearest Philippine island while it is 1,000 miles from Malaya. The control of the northern tip of Borneo by an unfriendly power would constitute a more deadly threat to the Philippines than would the island of Taiwan in the north in the hand of an enemy."

Hence, the proximity of Sabah to the Philippines border has always been regarded as very crucial to the security of the country. Nevertheless, the economic rationale of the Philippine claim to Sabah from the time of Macapagal until today is no less important.

According to Macapagal, "the territory, if reacquired by the Philippines, would be a boon to future generations of Filipinos."

In recent times, the political and security implications of the Sabah Dispute include: (a) the Moro secessionism in the South of the Philippines; (b) the alleged Malaysian assistance to Moro separatists; (c) alleged Malaysian incursion into Philippine waters; and (d) the issue of Filipino refugees and illegal immigrants in Sabah, which all the more has made the problem difficult to settle.

Malaysia has continuously benefitted from the abundance of Sabah’s natural resources and surrounding waters. Also, Sabah’s islands are some of the most attractive tourism hubs that contribute much to the coffers of Malaysia; making it all the more important to Malaysia.

Likewise, Sabah aside from the fact that it is rich in natural resources is also rich in oil, gas, timber, and palm oil. Thus, it is comprehensible as to why it is not easy for Malaysia to relinquish Sabah to the Philippines.

Maritime And Strategic Considerations

Another incident that has made the Sabah Dispute more complicated than it already is, was Malaysia’s submission to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLCS), a claim that its continental shelf is extended beyond 200 nautical miles in the northern part of the South China Sea on 12 December, 2019.

The continental shelf was projected from "portions of North Borneo" or commonly known as “Sabah,” which the Philippines had never relinquished its sovereign claims over.

In other words, Malaysia was claiming a continental shelf drawn from a territory that it has competing sovereign claims with the Philippines.

To note, the continental shelf is a geological feature: the prolongation of the coastal state's landmass, determined by geological investigation.

The proposed extension of the continental shelf submitted by Malaysia to the UNCLCS would logically and approximately encompass two-thirds of the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG) territory as well as a huge part of the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

On 6 March, 2020, through the Philippines representative to the UN, the Philippine government filed a note verbal protesting the Malaysian submission. The diplomatic note said: “The Malaysian submission covers features within the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG) over which the Philippines has sovereignty”.

In response to the said note filed by the Philippines, the Permanent Mission of Malaysia to the UN on 27 August, 2020 also submitted a note verbal before the UN.

The submission stated that “It wishes also to inform the Secretary-General that Malaysia has never recognised the Republic of the Philippines’ claim to the Malaysian state of Sabah, formerly known as North Borneo.”

In another note, Malaysia also rejected the Philippines’ claims to the KIG, calling it “excessive.” It said that the Philippines’ assertion over the KIG has also “no basis under international law.”

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the area 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) from a country’s territorial sea baseline is its exclusive economic zone, where it may exercise sovereign rights to use natural resources and jurisdiction to put up installations or structures. The law states “the exclusive economic zone shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.”

Conclusion

The tussle over Sabah between the Philippines and Malaysia with all its intricacies and current complications, no doubt, has left a mutual distrust between the two ASEAN member states.

The Sabah Dispute might either be idle or might amplify the current state of affairs of the bilateral ties between the two parties involved in the dispute, depending on how it will be politically managed by various actors in both countries.

Articles selected as Top Stories of 2020 are those that were the most popular among readers of The ASEAN Post for the month in question.

Anna Rosario Malindog-Uy is Professor of Political Science, International Relations, Development Studies, European Studies, SEA and China Studies. She has worked with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and other local and international NGOs as a consultant. She is President of Techperformance Corp, an IT-based company in the Philippines.