The first session of the 3rd Mekong Regional Land Forum looked to clarify an understanding of customary land tenure systems, and bring a focus upon communities living in and around forestland areas of the Mekong region. The session observed some of the policy developments that could lead to greater recognition of customary tenure and land security for community members.

Presentation 1

Introduction: Key Initiatives in Terms of Forest Allocation and Customary Tenure Documentation in the Mekong Countries

Natalie Campbell (Regional Customary Tenure Advisor – MRLG)

In an introduction to the concept of customary land tenure, Natalie Campbell provides a short overview of key principles, zooming in to look at Mekong region. There are many possible definitions, highlighting the complexity around the topic. Campbell proposes one possible definition:

Customary land tenure or customary tenure is a set of rules, norms, institutions, practices and procedures created by communities that have evolved over time. These rules & norms govern the allocation, use, access, and transfer of land and other natural resources.

Customary tenure can involve individual and collective parcels. It can also cover many types of land, such as agricultural land, forest, spiritual areas and residential zones. A frequent land use type involves rotational agro-forestry systems, which themselves vary in form. Customary tenure also incorporates different types of rights (such as access, duration, exclusion, management, alienation, withdrawal, and due process and compensation), which can be placed in different combinations. Arrangements are not static, but undergo changes due to socio-economic, environmental and political factors.

In the Mekong region, customary land tenure systems involve over 200 ethnic groups and over 70 million people. As Campbell puts it:

There are no communities without customary tenure and no customary tenure without communities.

The right to benefit from the land is critical for communities around the region, and competition for land towards investment projects and conservation needs demands a clarification of these rights. A few details are given on specific regional countries.

-

Cambodia is the only country in the Mekong region with a law recognizing and governing Community Land Titles for indigenous minority groups, even if the implementation of this law is a rather cumbersome process. In the Protected Areas Law (2008) communities should have access to land as Community Protected Areas (CPAs), but again there are issues around its implementation.

-

In Lao PDR formal land use planning has granted some land rights to communities in forest areas, although these encompass a limited bundle.

-

Myanmar has large areas of land under customary tenure. There has been a recent shift in policy declarations to acknowledge customary land tenure (such as in the 2016 National Land Use Policy). However, there has been no activation of these statements.

-

In 2016, 26% of forest areas in Vietnam were allocated to communities, but only 2% was allocated to collective community land. The 2017 Forest Law is the first legislation to acknowledge communities as being forest owners.

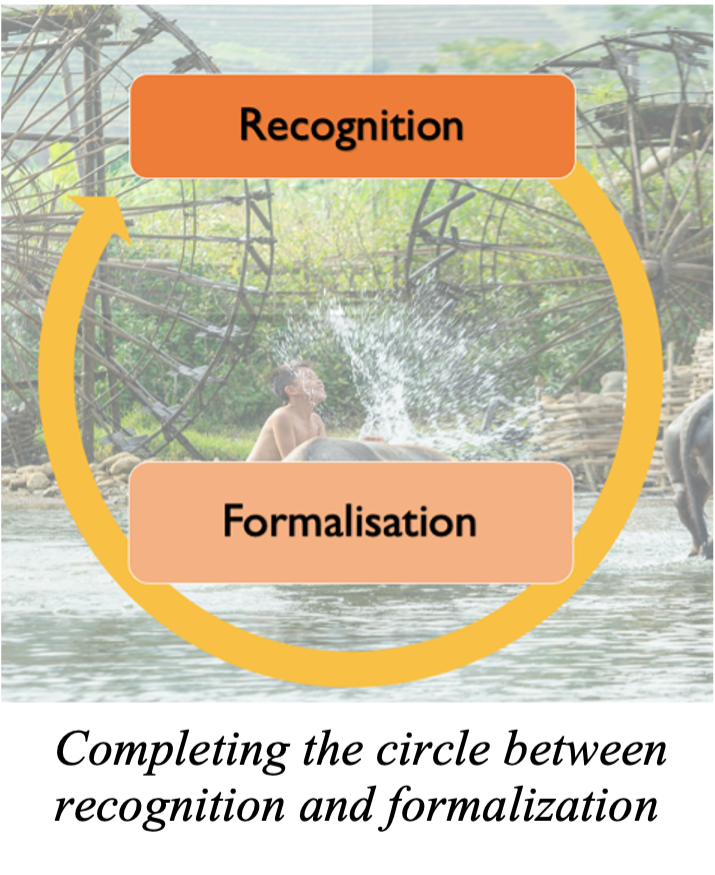

As a discussion point for the Forum, it is proposed that recognition does not inherently imply formalization,but can lead to it. However, even if formalization does take place, there may be further risks against the security of community lands. Therefore, formalization needs to be implemented on the ground, helping it become effectively integrated with the designated customary systems. This demands a completing of the circle between recognition and formalization (see figure).

Following this introductory view of customary land tenure systems, two further presentations looked at the situation in Lao PDR and Vietnam, using case examples.

Presentation 2

Lao PDR: Experiences in the Statutory Recognition of Forest Tenure Rights

Viladeth Sisoulath (Land Registration Component Team Leader – GIZ)

In Lao PDR, there are 49 officially recognized ethnic groups (it is important to note there is no use of the term indigenous in this country). However, there are no official records of land areas under customary tenure. From the National Land Use Master Plan, the Lao Government states an aim to achieve 70% of national land as forest. To reach this figure would involve the regeneration of over 6 million hectares of unstocked forests, potentially affecting 3,000 communities living inside forestland areas. This raises the question of how access to and use of land by these communities will be affected, and whether they will be able to maintain existing customary practices. There are various laws in Lao PDR that make reference to customary use. An example is the Forestry Law, although in looking at land usage rather than land rights, there is only a limited point of clarity. Article 44 of the Land Law offers a process to map, re-allocate and submit Land Use Certificates (LUCs) for forest land use. But due to its technical construction, and administrative capacity, it is uncertain whether this process can support the achievement of 70% forest land. There is a clear need to streamline the system.

Sisoulath introduces a pilot project in Khammouane Province, jointly implemented by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE) and Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF). The project represents an attempt to develop a streamlined system whereby land is mapped and registered in a national database (Lao LandReg). The goal is to issue formal land documents that are registered by both line ministries. Overall, there is a government consensus to recognize areas of permanent land use for forest communities. However, it seems unlikely that a full bundle of rights can be recognized at this point. Furthermore, there is no clear pathway for the recognition of non-permanent land uses.

To move forward, there is a need to develop tenure instruments within formal legislation that can be applied in forest areas. But this is just a beginning, and must be backed up by implementation and guidelines for implementors, under the support of sub-national line institutions and other land-related organizations and practitioners.

Presentation 3

Viet Nam: Forest Allocation for Community-based Forest Management

Ngô Văn Hồng (CEGORN - Center for Research on Initiatives of Community Development)

There are around 15 million hectares of forestland in Vietnam, which is nearly two-thirds of the total land area in the country. Of this area, 1.26 million hectares is under the management of 12,100 Community Forest Management (CFM) groups. There is a high ethnic diversity in these groups (54 officially recognized groups), who are dependent on this land and its resources for their daily livelihoods and spiritual needs.

Since 2004, the Vietnamese government has officially recognized the notion of community forest ownership in an attempt to shift from state to social forestry. Up to 2017, this is seen in legislation such as the Land Law, and the Law on Forest Protection and Development. The 2017 Forestry Law (which replaced the Law on Forest Protection and Development) lays some groundwork to establish long-term forest use and management by resident communities, including the recognition of their customary practices. For the first time, it legally recognizes that communities can be forest owners.

There are still a number of challenges concerning community forest management with a lack of clarity in present legislation, and weak relationships between local communities and government authorities. To point the way to new initiatives, Ngô Văn Hồng provides two case examples where the relationship has improved between local authorities and communities:

-

Quang Binh Province: Authorities have supported the Ma Lieng ethnic group, working with CEGORN, to connect with local markets for dried bamboo shoots.

-

Hoa Binh Province: A Muong community works with the NGO RIC (Center for Research on Initiatives of Community Development) to set up a Shan Tea Cooperative. This is a Community Forest Enterprise (CFE) approved by the local management board.

The main forest policy model is through the formation of Community Forest Enterprises (CFEs), which can be used for the sustainable management of timber, non-timber and ecosystem services, while supporting community livelihoods. However, there are still questions as to how communities successfully navigate the entry into wider markets, and what support is needed to avoid a loss of livelihood.

Panel Discussion

In a short panel discussion, led by Antoine Deligne (Deputy Team Leader – MRLG), two government officials reflected upon the session presentations, and highlighted promising developments in formal policy and information sharing around the region.

Bounpone Sengthong (Acting Director General, Department of Forestry, Lao PDR) has 20 years of experience in the management of forests in Lao PDR. He mentioned how the Lao government is looking towards the experiences of Vietnam in forest management, a cross-border process of sharing that will continue.

Tuyen Dinh (Officer of the Forest Protection Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Vietnam) highlighted how his organization has recently developed a handbook of guidelines on Community Forest Management (CFM), in partnership with MRLG.

Key Takeaways

Akiko Inoguchi (Forestry Officer, FAO)

-

Communities have for generations been self-sufficient in their practices to use land and forests, working under customary rules. This suggests that many of these practices are sustainable.

-

There are various forms of shifting or rotational farming, and their impacts differ, often but not always being sustainable.

-

There are lots of overlaps between designated forestland areas and residing communities (for example in Lao PDR), but there is a lack of clarity with which to govern this overlap. However, Vietnam shows promise with the Forest Law formally acknowledging forest ownership by communities

-

There are debates on the notion of formalization of customary tenure. Some see this as essential, but others state that once customary tenure is formalised, it is no longer customary tenure.

-

Customary recognition can make a difference, as witnessed by the positive community reaction in case studies in Vietnam.

Check further details on the 3rd Mekong Land Forum