Whether or not governments agreed enough to slow global warming at the COP26 meeting in Glasgow is up for debate. But Indigenous Peoples, at least, did not come away empty-handed: their views were listened to and, in some cases, appear to have been taken into consideration.

It was clearly stated, for example, in the $12 billion “Global Forest Finance Pledge” signed by 11 rich countries and the European Union, that part of the money would be used for supporting “forest and land governance and clarifying land tenure and forest rights for Indigenous Peoples and local communities”.

More specifically, a group of these countries joined with foundations to pledge an initial $1.7 billion of financing, through to 2025, to support the advancement of Indigenous Peoples’ tenure rights and provide greater recognition and rewards for their role as guardians of forests and nature.

Although this is certainly significant politically, whether it is enough support or will be used properly remains in question. Governments have pledged money on the international stage in the past only to fail to come through with it, or to water it down by including previous spending in the pledge, or to channel it through inappropriate channels.

How this is likely to play out will be topic of the next Land Dialogues webinar “Financing Land Rights: Investing in People and Nature” to be held on November 18 under the auspices of the Tenure Facility, Land Portal, and Ford and Thomson Reuters foundations.

Among the panellists will be Tuntiak Katan, general coordinator of the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, which encompasses people from the rain forests of Latin America, Africa, and Indonesia.

Katan has welcomed some of the COP26 decisions relating to Indigenous Peoples, but he remains cautious about their implementation.

“We will be looking for concrete evidence of a transformation in the way funds are invested,” he said in a statement disseminated by the UK government organisers.

“If 80 percent of what is proposed is directed to supporting land rights and the proposals of Indigenous and local communities, we will see a dramatic reversal in the current trend that is destroying our natural resources.”

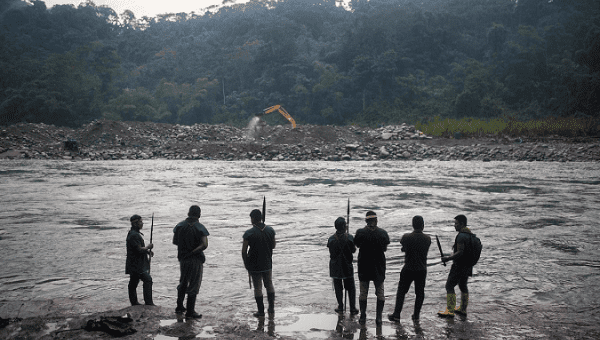

Such investment is crucial to environmental protection given the evidence that Indigenous Peoples are the best guardians of their lands, primarily the forests that soak up the CO2 that is causing global warming. When they have land tenure, Indigenous Peoples can conserve such areas with traditional methods while at the same time providing a bulwark against unfettered industrial and agricultural exploitation.

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, for example, estimates that between 2003 and 2016, Amazon Basin indigenous territories lost less than 0.3 percent of the carbon in their forests versus 3.6 percent lost in areas that were either non-Indigenous or not otherwise protected.

SHOW ME THE MONEY

Katan’s caution – his call for evidence of action rather than intent – is based on experience. Indigenous Peoples are often side-stepped in the name of progress, whether it be corporate or environmental. (A new struggle, for example, is against the imposition of massive green projects on Indigenous territories, as explained here.)

This was clearly enumerated earlier this year in a report – “Falling Short” – by the Rainforest Foundation Norway, which has previous reported that over time a third of tropical rainforest area has already been lost across the world, while another third has been degraded.

The key finding was that between 2011 and 2020, projects supporting land tenure and forest management by Indigenous Peoples and local communities received approximately $2.7 billion from bilateral and multilateral donors and private donors.

That amounted to just $270 million per year, or – and here is the real proof of neglect – the equivalent of less than one percent of Official Development Assistance for climate change mitigation and adaptation over the same period.

It is for this reason that reaction to the certainly welcome inclusion of Indigenous Peoples’ rights and funding for land tenure has generally come with caveats.

Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, one of the sponsors of the Land Dialogues webinars, described what happened regarding Indigenous Peoples in Glasgow as “historic”.

But in an interview with The Guardian newspaper, he was also circumspect about the impact of the financial moves.

“It’s a first step, it’s a down payment,” he said.

This piece was originally posted on the Tenure Facility's website.