Resource information

From the DEI Working Group[1]

Abstract

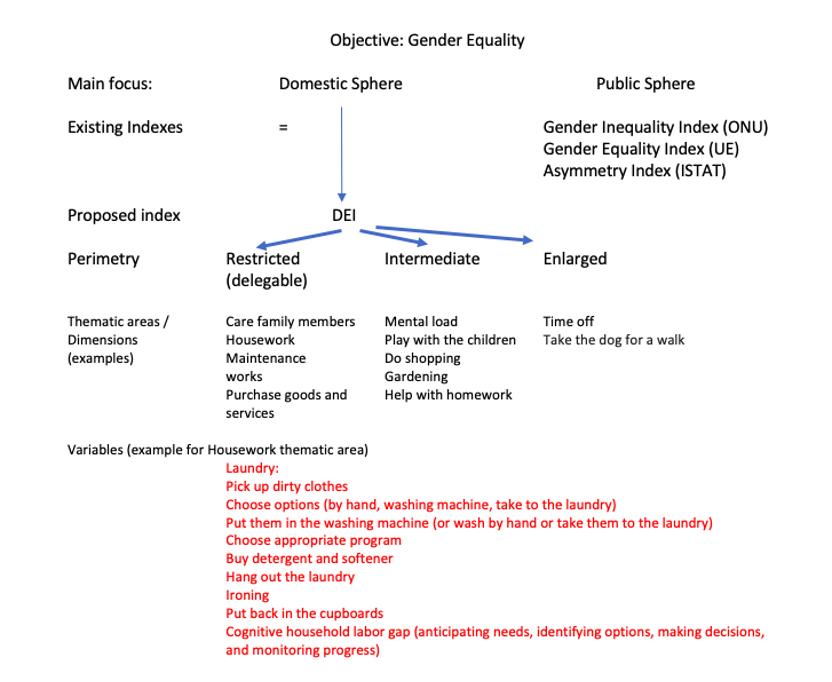

This research paper discusses the pervasive gender inequalities that limit individuals' choices and opportunities in all aspects of life. While this issue is particularly relevant in rural and disadvantaged areas, it still holds value in modern rich and developed countries. This paper calls for a shift in focus beyond workplace equality and monetary representation of gender disparity, and highlights the importance of recognizing unpaid domestic and care work, as well as cognitive labor and other aspects of domestic gender equality. The paper builds on existing conceptual frameworks to introduce a Domestic Equality Index (DEI) to measure and promote gender equality in the domestic sphere. It also emphasizes the need for collective action to achieve a more equitable distribution of household tasks.

Introduction

Gender inequalities are often discussed in terms of wage gap between men and women, women's participation in the labor market, or the number of femicides or rapes. Gender inequalities are measured in areas where they are most evident and through data that are more easily collectible and available. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that over time, there has been recognition that gender inequality affects individuals in all aspects of their lives, limiting their choices, rights, and opportunities. This is reflected in the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 5, which includes targets such as 5.4 - Recognize and value unpaid domestic and care work, provide public services, infrastructure, and social protection policies, and promote shared responsibilities within families, in accordance with national standards.[2]

The most frequently discussed themes related to gender equality, such as equality in the workplace or gender-based violence, are the result of the differentiated value that society assigns or has assigned to men and women. As French feminists Françoise Héritier-Augé and Pascale Molinier would say, there is a differential valence of women and men: "all characteristics generally associated with men, such as strength, masculinity, boldness, are valued by society. Characteristics such as kindness, gentleness, are generally considered as feminine and devalued".[3]

The indicators used to measure equality are a reflection of how our societies attribute value to different activities. Some progress has been made in recognizing women’s fundamental role and contribution in areas traditionally considered outside of monetized economics, such as domestic work (for example, in SDG5 indicators - target 4)[4]. However, countries are reluctant and slow to collect data, leading to a lack of evidence.

There are various attempts to address (or just understand) gender inequalities. Seymour et al. (2020) make use of the Women Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) in Bangladesh, focusing their analysis on the empowerment of women. Another example of studies on empowerment is Hickman et al. (2022). Field et al. (2023) focus on time-use, and building up on existing literature they propose new modules to better capture data from the field. Other examples on time-use include Eissler et al., 2003, There are also steps toward the creation of national metrics for women’s empowerment (see Heckert et al. 2023).

While we build upon existing literature, we believe that developing an index specific to domestic equality meets other needs. For instance, we think of developing a tool that is suitable for different contexts, with the due adjustments. Second, we believe that such an index might encompass a broader range of attributes than time-use or empowerment. Third, we believe that the tool is only one part of the approach we want to propose. We think in fact that a relevant role is played by the process where the two parts (i.e. the partners, or communities, or other social gathering environments) negotiate what indicators are to be included in the final index. This indicator is designed for a specific audience, namely those groups, associations, movements, and/or political parties that take public positions in favour of gender equality. Within each of those groups, we propose to collect data that will show the domestic balance between partners.

While existing research primarily focuses on the quantitative aspects of gender inequality in domestic labor and care work, this paper offers a novel approach by incorporating qualitative dimensions, such as emotional labor and time poverty, to develop a comprehensive Domestic Parity Indicator that challenges traditional, market-based solutions.

Our study fills a critical gap in the literature by moving beyond a mere description of the problem to proposing a concrete, community-driven solution that addresses the root causes of gender inequality in the domestic sphere.

In order to develop this index, we organized the paper as follows: part 2 provides a literature review. Part 3 presents the target of our index. Part 4 depicts how to calculate the index. Part 5 presents our working hypothesis. Part 6 concludes.

Literature Review

The existing indicators commonly used to measure equality, such as the gender pay gap, are a dogmatic reflection of how our Western, neoliberal social order attributes value to different activities; often, this involves some sort of potential or actual financial gain. Nevertheless, over time, some progress has been made in recognizing women’s fundamental role and contribution in areas traditionally considered outside of monetized economics, such as domestic work (for example, in SDG5 indicators - target 4). However, countries are reluctant and slow to collect data, leading to a lack of tangible evidence. Aside from a survey by Indesit, which found that 79% of Italian women usually plan most household chores, and 76% assert to do most of the work, data on household labor division is limited for Italy. With the pandemic, the situation has worsened. In France according to the Observatory of Inequalities, there has been no progress in sharing domestic and family tasks. The latest figures in France date back to 2010, as provided by the Time Use Survey (INSEE, 2010). The survey indicated that 72% of women were responsible for domestic tasks such as childcare, cooking, cleaning, laundry, and ironing. The National Institute of Statistics reported that in Spain only 50% of families share household chores equally. Women end up doing more in 46% of families, while in just 4% of households men do more. Globally, time use surveys reveal significant differences between genders with regards to time spent on domestic and care work, especially in low and middle-income countries. On average, globally, women dedicate 4.2 hours per day to unpaid domestic and care work, compared to 1.9 hours for men.

In addition to this already dire situation, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an increase of women's care work. The closure of schools and interruption of services have led to multiple care responsibilities for women, resulting in an increase in their unpaid domestic care work. Consequently, the gender gap in care work between women and men increased from 1.8 in March 2020 to 2.4 in September 2021.

Lastly, gender inequalities in unpaid domestic and care work tend to be greater in rural areas than in urban areas, and when care work is considered as a secondary activity. This is true globally although there is heterogeneity across countries. In a sample of five countries and predominantly rural settings, women spent an average of 7.0 hours on unpaid domestic and care work, compared to an average of 1.4 hours for men.

Not only is the available data on this matter rather limited, but the current literature on the gendered crisis of care and household labor inequality does not propose a viable solution to this social ill. By relying on current social constructivist, Marxist-feminist understandings of gender and social reproduction, we aim to develop a domestic parity indicator (DEI) as a tool for monitoring, encouraging, and advocating for tangible gender equality. In the following section we will elucidate the relevant theorizations which we rely on conceptually as an analytical base to develop our index, and to further highlight the urgent need to tackle domestic labor inequalities to ensure a more just and equitable social order.

Key gender theorist Judith Butler (1990) understands the construction and perception of gender through her concept of performativity, whereby gender does not exist in objective reality or nature, but it is a cultural identity created through repeated behaviors which act as indicators of one's gender. Throughout this initial paper we use the words “woman” and “man” throughout. These words aren’t limited to cis-gendered individuals, as we do not view gender in a sex-based, binary and positivist manner: “woman” and “man” can be attributed to anyone who desires to be labeled as such. Since household labor disparity is mostly evident in female-male dyadics, and as our advocacy tool aims to create awareness and bring change to such dynamics, we are currently not using gender neutral language (to identify non-binary individuals) in order to highlight the gendered nature of this social ill through our use of language. At the same time we hold space for queer couples, queer sexual identities, and any other identities beyond the gender binary in our questionnaire, as we also aim to measure how care work is divided in any other dynamics.

In our patriarchal social order, the automatic attribution of qualities considered inherently 'masculine' or 'feminine' to individuals of a particular sex is intimately linked to a value judgment that devalues or does not recognize the 'feminine'. This gendered attribution of qualities and the overarching power relations are not a universal phenomenon, but rather a product of Western discourse, as demonstrated by Oyĕwùmí (1997), who sheds light on how Yoruba society did not adopt the concept of gender as an organizing principle before being colonized, which led to the inferiorization of women. The asymmetrical valuation of gender has a myriad of implications, including the uneven distribution of domestic work between women and men. Relying on critical theory, we build from Karl Marx and go towards feminist Social Reproduction Theory, following scholars such as Silvia Fedirici (2004), Mariarosa Della Costa (1972), Tihti Bhattarcharya (2017), and Nancy Fraser (2016). As argued by Sivlia Federici (2004), the emergence of the capitalist system introduced profound transformations towards the degradation of women. Women’s bodies became a machine to reproduce the workforce, and, given the privatization of land and the growing importance of monetary relations, women had more difficulty in supporting themselves compared to men, thus were forcefully relegated to the domestic sphere to reproduce the (male) worker (p. 74). It is also crucial to acknowledge the seminal publication of Mariarosa Dalla Costa (and Selma James’ contribution), which for the first time emphasized the centrality of domestic and care work in reproducing the labor force necessary for the capitalist system. Labor that is referred to as "unpaid work" in the language of the time.

This unpaid work can be defined as societal reproduction, which are all the processes that enable the labor force to be productive in the workplace, such as maintaining the household and caring for family members, involving mental, emotional and physical work, that tends to be disproportionately done by women (Bhattarcharya, 2017). Without social reproduction, the worker cannot go to work. An effective synthesis is suggested by Srishti Khare, who states that men are able to be productive in the economy due to the reproductive, unpaid, and unacknowledged household labor that women devote their time to . It is therefore a fundamental aspect of capitalist relations, that however has been put aside: the "revolutionary" intellectuals of the time did not prioritize this issue and minimized Dalla Costa's work to the point that feminist issues were categorized as "secondary contradictions of capitalism". "[...] .

Traditional political organizations have always considered this space as a "place of political backwardness," failing to realize its growing importance as the social and political hub of the entire capitalist system, as Leopoldina Fortunati explains in the above-mentioned article. This differs from feminist views in political economy, which emphasize the significance of comprehending "systemic relationships between domestic, economic, and political structures". Notably, feminist economists Pearson and Elson question the segregation of the 'production' realm from the domestic sphere, which remains invisible and easily exploitable by the state. Consider, for example, how women's labor compensates for the shortage of available childcare and elderly care services. Carole Pateman, a British feminist and political theorist, cited by Diana Sartori, went so far as to say,

"The dichotomy between the private and the public is central in almost two centuries of feminist writings and political struggle; it is, ultimately, what the feminist movement is about".

It is important to mention that, in this research, we consider unpaid care work beyond physical labor. It also includes the "mental load," which is defined as the combination of “cognitive household labor” and “emotional work”. “Cognitive household labor”, involves anticipating, fulfilling, and monitoring household needs, falls disproportionately on women, with Weeks (2022) finding that women are responsible for 70% of “cognitive labor” compared to men's 30%. While existing research has only focused on the cognitive aspects of household labor (Catalano, 2022; Daminger, 2019; Robertson et al., 2019), the inclusion of the emotional aspects is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of mental load. We follow Dean et. al. (2021), who have expanded the theorization of “mental load” to include “emotional work”, alongside “cognitive labor”.

American Sociologist Arlie Hochschield (1983) was the first to coin the terms “emotional labor” and “emotional work”. While the former is directed at paid work - mostly done by women - which requires a high degree of “emotional labor” (she analyzed flight assistants being instructed to manipulate their behavior towards problematic passengers, leading to a commodification of empathy), the latter is directed at private contexts and non-paid work, such as household labor. “Emotional work” is defined as the effort to manage an emotion through "deep acting" (Hochschild, 1979, p. 561), which further contributes to the complex and often unrecognized burden of unpaid care work predominantly shouldered by women. “Cognitive household labor” cannot be separated from “emotional work”: most cognitive tasks related to the household require “emotional work”, as these tasks may a) be done out of care for loved ones, and b) may induce managed emotional responses to fulfill expected gender roles (women are expected to be “naturally” loving and accommodating. Thus a woman who is tired and frustrated due to inequitable distribution of household tasks may resort to “deep acting” to manage her emotions and fit into her expected gender roles). More generally, it is usually women who need to ensure that a family’s emotional needs are met, which is a further form of “emotional work” (Bass, 2015; Wong, 2017, as seen in Dean et. al. 2021).

Although there has been a greater recognition of this social ill, the unequal division of care work and domestic labor persists, though less pronounced than in previous times. While the current “progressive” forces have begun confronting this issue due to the influence of internal and external feminist movements, the current rhetoric of equality fails to translate into concrete actions that go beyond the market. Solutions have been sought through massive processes of simplification, standardization, automation and outsourcing of domestic tasks, both material and immaterial — education, emotions, entertainment, communication, and information. As Leopoldina Fortunati recalls, the domestic sphere's importance is evident as both the state and families are forced to compensate for reduced household labor, also due to women's increased workforce participation. The state allocates some funds for education, healthcare, and pensions, while families often rely on migrant women for domestic and care work.

In her article “Contradictions of Capital and Care”, Nancy Fraser (2016) elucidates her thoughts on the most recent developments of the crisis of care. In today's financialized capitalist social order, where austerity measures against social welfare have become the norm, care work becomes a (gendered and racialized) commodity for those wealthy enough to purchase it, and privatized for those who cannot. Still today, all emancipatory fights have been engulfed by neoliberal thought, including the feminist movement. The route to liberation has been defined by the market: (white) women are just as capable of production as men, hence the two earner family model has become normalized as opposed to the family wage dynamic. This neoliberal and imperialist feminist outlook has, however, brought a further issue. A care gap filled by migrant women who perform household labor for those of higher social classes, leading to a global care chain. Demazière, Araujo Guimarães, and Hirata, or Christelle Avril and Marie Cartier further delve into the issue of outsourcing of domestic work and its connection with migrations and recent capitalism. The problem of household labor has therefore not been eradicated, but rather displaced from the Global North to the Global South. This change has emerged due to an increasingly important, capitalism-induced social problem: time poverty.

The concept of "time poverty" (resulting from the unequal distribution of domestic tasks) is emerging in international discourse. Focusing on those who privatize care work, it is once more the women in the nuclear family who work (including both paid work and domestic work) 11 hours a week more than men, according to the European average. In Italy, this disparity amounts to 13 hours. In other words, "200 percent is the percentage of extra time that in 2014, Italian women in full-time employment with at least one child under the age of 14 dedicated to household chores in a midweek day compared to their partners." . It is needless to say that time poverty also affects those women who are not part of the labor market, as their free time also gets unequally distributed and heavily reduced due to disparity in household labor.

As Srishti Khare reminds us, time is a highly political resource, as it is entrenched in power dynamics: those in power determine how much time is to be allocated to whom, who controls it and how it is distributed. It is therefore vital for men to devote time to household chores rather than simply providing financial support, as it is instrumental in freeing up women's schedules. How women decide to use this newly acquired time is a personal matter and does not concern us.

Based on the long-standing advocacy of women agricultural workers from the Unión de Trabajadores de la Tierra, an Argentinian agricultural labor union, who push for men to take on their share of domestic work, the core issue centers around time management and the distribution of time to various tasks needed to sustain a couple/family of any kind. Therefore, we propose a concrete approach that doesn't rest on further oppressive capitalist means to encourage a solution for the care crisis. We go beyond monetization, and rather focus on time as a scarce resource.

A further reason as to why we do not focus on monetary aspects is because monetizing domestic work carries implications for women's gender roles by potentially incentivizing them to remain in the domestic sphere, as is occurring with marginalized women from the Global South who are forced to dedicate their lives to paid domestic care work. If domestic work were to become paid labor, it would undoubtedly recognize the value of the time mostly devoted by women, but it could also risk confining women within their homes. Statements such as, "Since you already have work to do at home, why seek additional work outside?" and "Women have authority within the home," might be used by proponents and conservatives to maintain male dominance in the political and economic sphere, resulting in women bearing the responsibility of household management. Additionally, there is a risk of perpetuating a hierarchy that devalues women's work and further marginalizes them.

Considering the above mentioned reflections we will develop the Domestic Parity Indicator (DEI) by relying on the concept of time poverty. Our proposal is to exclude domestic work from the GDP, as some ongoing work suggests. For example, INSEE (the French Institute of Statistics) has estimated the number of annual hours spent on domestic work in France to be between 42 and 77 billion hours, depending on which "domestic chores" are counted. If these hours were monetized, they would amount to 19% to 35% of the GDP. However, this school of thought is not aligned with our views, elucidated above.

With this research we aim to encourage men to devote an equal amount of time to household chores, allowing them to reflect on and deconstruct their gender roles, rather than just contributing financially to the nuclear family unit, in order to free up women's schedules and alleviate them of time poverty. We have conceptualized an analytical framework to capture the gender disparity related to time poverty in the domestic sphere by focusing on measuring various physical, cognitive, and emotional household labor activities. By creating a monitoring index focused on encouragement and advocacy that is easy to implement, our aim is to increase awareness of existing disparities, rather than relying on market-focused neoliberalist “solutions”. Moreover, the issue of the unequal distribution of domestic work has also been addressed in the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) Voluntary Guidelines mentioned earlier., the text places the primary responsibility on governments, without securing an equal commitment from progressive forces (movements, associations, parties) that could contribute to addressing the power imbalances that are at the core of the unequal distribution of care and domestic work. To counter this short-coming, we will co-construct the indicator with various bottom-up institutions instead, relying on a community-participatory methodological approach. Lastly, we are going to gather data regarding emotional work, which is an under-researched concept that in existing research tends to become engulfed by cognitive labor, fueling outdated emotion/cognition dualisms.

Target of the DEI

A significant portion of indicators (economic, social, environmental) is based on the principle of comparability. Indicators related to poverty, income, longevity, and education allow for individual and comparative analysis of societies, providing insights on a country's position over time and space relative to others.

Because of the structural nature of standard indicators, a set of variables is measured through data collection using either closed or open-ended questionnaires. The respondents have limited freedom due to the type and quantity of questions asked. Although the survey offers a choice between closed or open-ended questionnaires, these options are still within the predetermined space set by the organizers.

Historically, due to the influence of mathematical economics (and Western influence), the measure of a country's well-being has been Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita , divided by the number of inhabitants. The next step involved analyzing the distribution of this income among different segments (deciles) of the population to understand the inequality of distribution (e.g., the Gini coefficient). It took many years before the focus shifted toward "human" development, necessitating the incorporation of non-economic indicators while still ensuring adherence to the comparability framework.

The process of data collection is crucial for any indicator, whether it is economic, social, or environmental. Often, this process has typically focused on data provided by statistical institutes, with technical support provided, usually from Northern countries, to ensure that the data collected is suitable for international comparisons. The top-down nature of these indicators, designed by experts and imposed on vastly different local realities, appears relatively uncontested, except for isolated cases like Bhutan, which prefers a Gross National Happiness indicator over GDP per capita.

In this study, we have opted for an alternative methodology, ignoring spatial comparability between countries and instead focusing on temporal comparability through examining the value of the indicator at time T0 and subsequently at moments T1, T2, ....

The first structural change we have introduced is related to the method of co-construction of the indicator. The first part of this text presents the conceptual foundations. However, to operationalize the indicator, we envision a phase of dialogue and negotiation with the counterpart institution (association, movement, political party, or other), to enhance their sense of ownership and, consequently, their willingness to implement not only the DEI but also the measures needed to improve the situation over time.

DEI is conceived as a tool to stimulate and promote processes that lead to genuine gender equality, a mission that should be of interest to all movements, associations, parties, or other entities that publicly pledge to uphold gender equality and gender-responsive policies. The absence of references to the domestic sphere means that all these public commitments are considered applicable only to the public sphere, a crucial but less structural aspect of power dynamics in the private sphere.

Patriarchal power relations are evident in the private sphere where they create the material foundation for the reproduction of the overarching capitalist economy in a subtle and structural manner. In the domestic sphere, labor is reproduced freely alongside the relations of male dominance over women, which parallel the domination of men over nature.

Therefore, it is crucial to address the persistent and structural nature of patriarchal power. We provide a tool crafted for this purpose. In order to establish a tangible and shared value, it is crucial that the counterpart organization (association, movement, political party, etc.) participates and becomes a key player in the construction, use, and subsequent monitoring of the DEI. In essence, the DEI must become "theirs." Demonstrating the improvement of the value of DEI over time will enhance its credibility in advocating for improvements in the domestic sphere after identifying asymmetries at time T0. In fact, at T0, DEI serves to numerically represent the actual distribution of work and underlying power dynamics within couples/families supporting the alignment of public discourse on promoting equality with the identification of concrete internal practices.

One potential risk to avoid is failing to consider the power imbalances that may exist within the dominant groups of organizations, movements, and parties with whom we plan to collaborate. The reality is that leadership roles in these institutions are often male-dominated, indicating the influence of patriarchy on our cultural formation and shaping of institutions. If this dimension of patriarchal power is not addressed, there may be a risk of exercise manipulation. We highlight the importance of the negotiating aspect as all stakeholders, both male and female, must have the chance to voice their opinions during the decision-making process.

Therefore, delegating the final choice of activities to be measured solely to the counterpart's leadership[5] will not suffice. It is crucial to have accompanying "facilitators" who are aware of the potential risk involved. This does not imply that the executive boards of various associations, movements, parties, etc., are inherently sexist; rather it highlights the existence of a that must be minimized. The preliminary discussion before the negotiation phase is crucial and requires adequate time allocation. The higher the level of coordination in the negotiated list, the greater the likelihood of achieving an accurate representation of the situation. This is a crucial starting point for progressing toward improvement.

It is also important to note that the intention is not to blame the partner who does less or nothing at all. Rather, the purpose of the initial dialogue and negotiation is to increase their explicit awareness of the activities necessary to sustain a couple or family. This awareness should lead to an active commitment from them.

How to Calculate the DEI

Methods and conceptual framework

The concept behind the DEI is to combine various indicators into a single aggregated index. As such, two key questions must be addressed: 1) the analytical framework explaining how the set of indicators represents domestic equality, and 2) the weighting of the indicators.

Regarding the first point, it is crucial to establish a comprehensive list of tasks that are representative of domestic life. In the absence of a universally recognized analytical framework, it is still necessary to build upon existing literature. By aggregating domestic tasks into dimensions, power asymmetries can be effectively identified. In the literature, there are at least four examples that can serve as analytical references. One approach is the "time" component of the Gender Equality Index by EIGE[6] (2012). Another one that Rodsky[7] (2020) proposed. Also, relevant is the asymmetry index developed by the Italian Institute of Statistics ISTAT[8] (2020). Lastly, there is the approach suggested by the French Institute of Statistics[9] (INSEE).

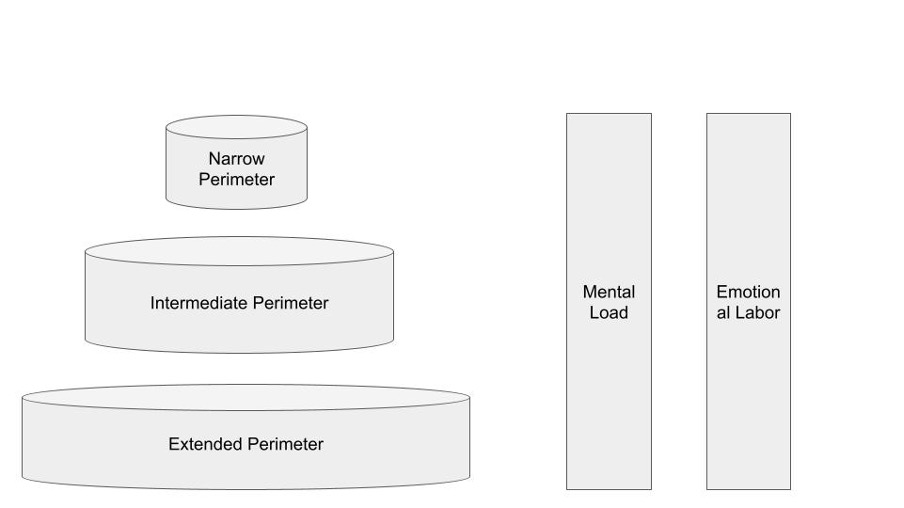

In the DEI, we have decided to build the INSEE’s framework for reasons we will elaborate upon. INSEE structures its conceptual framework for domestic work around three perimeters:

A narrow perimeter that encompasses the "core" activities of domestic work, which are widely acknowledged and rarely disputed. These include domestic chores, maintenance of the households, washing dishes, doing laundry, ironing, shopping, cooking, and providing care both for children and dependent persons. All of these tasks can be delegated or outsourced, and there are market substitutes for them, such as laundries, dry cleaners, restaurants, childcare providers, domestic help, drivers, and personal assistants (concierges).

An intermediate perimeter which includes activities that people are more inclined to do for pleasure and that often take longer than strictly necessary, in addition to the first list of productive and "delegable" activities. This second list comprises semi-leisure activities such as sewing, DIY projects, gardening, hunting, and fishing. For INSEE, shopping is also included in this second list because their survey does not distinguish between daily shopping and general shopping.

An expanded perimeter which also includes travel times, car trips, and walking the dog.

We choose to begin with what INSEE proposes because it appears to be the most flexible and unbiased conceptual framework. The use of perimeters, instead of other categorizations (e.g.: by activity), enables the automatic inclusion of cultural differences and economic availability. We do not have categories that may be more relevant in one context than in another. Instead we measure activities based on their proximity to the family core and their level of essentiality for the smooth functioning of daily domestic life.

In addition to the INSEE's framework, we add an element that we consider fundamental, derived from Catalano Weeks’ work: the "cognitive household labor gap". This refers to aspects such as anticipating needs, identifying options for fulfilling them, making decisions, and monitoring progress[10]. This translates into a mental load that must be considered in any endeavor to quantify the burden of family management.[11] This is because it is not solely about things "to do"; many of them also need to be "thought about" in advance, "remembered" without needing to be reminded by the other person, "planned," and "constantly monitored." While we refer readers to Catalano Weeks’s works for further insights on this matter, it suffices to mention that we will integrate some aspects of this work into the perimeters adopted from INSEE's framework. We also add the emotional labour as described in the literature review section.

We propose a primitive visualization of the conceptual framework here:

Several indicators will be collected for each perimeter pertaining to activities that occur in that context. The final list of indicators will be subject to negotiation with the counterpart institution collaborating in the DEI implementation.

For instance, consider the task of doing laundry. It may seem simple and straightforward, but upon closer examination, it involves several steps starting with gathering and placing dirty clothes in a laundry basket, followed by transport to the washing machine, adding clothes, separating whites and colors to avoid bleach mishaps, and selecting the appropriate washing cycle. These sub-activities also involve remembering to buy detergent and fabric softener. Once the washing machine cycle is complete, who is responsible for hanging the clothes to dry? Then, who folds and subsequently irons them before finally placing them in their designated drawers or closets? All these activities may be obvious from a female perspective but not necessarily || from a male perspective. They all take time to do but also to think about (e.g., if I want to wear that specific shirt, have I taken care of the detergent-fabric softener-laundry basket-dirty laundry-washing machine-hanging-ironing-organizing in the drawer chain that is essential to have "that" shirt ready for use when I want it?) and, of course, the monitoring of the said progression in its entirety.

To be even more comprehensive, we should also consider a multiplier that we could call "concentration disruption." When one of the two partners is engaged in an activity that requires intellectual concentration, interrupting this activity to attend to a domestic task does not merely count as one more activity; it effectively breaks the logical train of thought they were working on. We will leave this aspect open for the time being but acknowledge that we should dedicate more attention to it in the future.

This is why the negotiation process with the representatives of the institution we will work with becomes crucial. By determining the list of activities (questions) to be included (or excluded), a more accurate and useful indicator will emerge.

It is useful (and necessary) to note that the activities and questions to be examined will vary depending on the specificities of the counterpart institution. If the counterpart were a peasant movement, particularly perhaps in the Global South, activities such as fetching water, gathering firewood or forest products, honey collection, and much more should be taken into consideration. While adapting the questionnaire to local and socio-cultural specificities may sacrifice generic spatial compatibility, it is still a crucial step due to the co-constructive nature of the DEI. The full meaning of the process is realized through dialogue and negotiation, thus making it more suitable and acceptable in various situations.

Weighting the indicators

To assess how the performance of activities within a couple varies, we have three possibilities:

a) We assign equal weight or value to each indicator (and therefore activity), so that the partner performing that activity is assigned a value of 1.[12]

b) We measure the time required to complete the tasks, or

c) We measure the monetary value of the tasks.

Option a) is the simplest but neglects important differences between the indicators. While taking care of a child's emotional needs may demand a significant investment of time and energy, it does not have a direct monetary cost (although it entails an opportunity cost for the parent who opts to stay with the child instead of working or doing something else). A clear advantage is the removal of subjectivity from the partners' choices (when assigning different weights to different tasks, the interviewer introduces an external element of subjectivity). From an agreed-upon list, all tasks must be performed. The frequency considered necessary is the only variable, which becomes irrelevant when measuring task completion rather than time spent on it.

Option b) is ideal for taking into account how much time parents have left for other activities (leisure or work). This approach is adopted, for example, by ISTAT in their asymmetry index. However, it has the disadvantage of not taking into account the financial effort required to enable certain activities. If one parent can afford to spend time with their children, it is because the other earns enough to support the entire family. Alternatively, engaging in certain creative and recreational activities with children is only possible if the family has the financial resources to purchase these services.

The main problem with this approach is that it introduces an element of differentiation (e.g., I am faster than you because you do not know how to do it, or conversely, I take more time because I clean more thoroughly than you). In this way, adopting this approach does not lead to a "solution" but makes the problem unsolvable.

Option c) would certainly please the proponents of neoliberalism, where everything is measured in monetary terms, thus reviving the old debate on domestic wages. We have mentioned this option for the sake of transparency, but it is clear that it is not consistent with the scope of this work. The fact that some tasks can be outsourced (e.g., care of the elderly in nursing homes) introduces an element of differentiation (of class, in Marxist terminology): those who have the money to pay, and those who do not have. However, the ultimate reason that compels us to eliminate this "solution" is that it risks freezing the existing asymmetrical social roles. Referring to the group Lotta Femminista, which first initiated this debate in Italy in the early 1970s, and following the reflections of Mariarosa Dalla Costa, we reiterate that: "We want to avoid, through this request, the institutionalization of the role of the housewife. That is precisely why activists reject and invite others to reject... housework as women's work, as imposed work that women have never invented".[13] The path to gender equality involves freeing women's time (allowing them to decide how to use it) and involving men more in sharing domestic tasks.

Based on the above, our choice is to consider all activities on the list equally. Consequently, we proceed to sum the activities without distinguishing between more or less valuable, tiring, or time-consuming activities. Too many subjective socio-cultural parameters could influence any financial or time-related parameters, thus introducing bias into the measurement of the DEI.

Starting with a indicative list (which, as we mentioned, must be completed through an initial negotiation between the parties, both as regards the specific tasks of each perimeter and as to the weight to be assigned to the various perimeters), we have a total of X activities, to which values are assigned as follows: -1 if they are performed solely by partner A; -0.5 if they are mostly performed by partner A; 0 if they are performed evenly by both partners A and B; +0.5 if they are mainly performed by partner B; +1 if they are performed solely by partner B.

For interviews, we will use a statistically representative sample of the population under study. An introductory anonymous form will be used to record the characteristics of the responding partner.

As a result, our indicator will have three possible extremes:

DEI = 0 perfectly balanced couple

DEI = maximum negative value (a couple where all activities are performed solely by partner A)

DEI = maximum positive value (a couple where all activities are performed solely by partner B)

|

A Only |

A Mostly |

A and B |

B Mostly |

B Only |

|

-1 |

-0.5 |

0 |

+0.5 |

+1 |

It is important to remember that this indicator aims to observe the trend from one moment (T0) to the next (T1) and beyond (Tn). Therefore, it is not the absolute value per se that is important, but rather whether, during the observation period, the couple or the responsible organization, party, or movement has encouraged activities promoting greater domestic equality. In this sense, comparability between different groups is less critical than the movement of the indicator itself, making it a tool for political advocacy.

If some activities are delegated to third parties (male or female cleaners, babysitters, etc.), these are excluded from the final calculation (as explained further below).

Hypothesis/Research Questions

The hypotheses underlying this indicator depend on the type of couple/family and their social status. One of the interesting aspects of this indicator is its ability to highlight the heterogeneity of the domestic balance in different gender couples. We will also have the opportunity to consider whether external help is available for the activities listed.

The first hypothesis is that inequality is lower in same-sex couples (two men or two women), than in heterosexual couples. This hypothesis is linked to the lower impact of gender stereotypes in same-sex couples and the lower presence of children (linked to the greater difficulty in procreation or adoption in certain countries).

The second hypothesis is that for couples with more than one child, inequalities within the couple increase. According to INSEE data on part-time work in France, there is a correlation between the number and age of children and the percentage of women and men in part-time employment.

According to data reported in 2019, more women have part-time contracts as the number of children increases, , while the opposite is true for men. It could be inferred that the choice of part-time work is linked to domestic and child care responsibilities. In practical terms, we suggest that an initial question be asked to both partners to determine the number of dependent children (whether they are their own children or children from a previous relationship). During the analysis of the results, it will be possible to explore the significance of this variable and the distribution of tasks.

The third hypothesis is to consider that wealthier families are more likely to outsource certain domestic activities (cleaning, cooking, part of child care, etc.). However, the outsourcing (or outsourcing) of care has an impact not only on gender inequalities (because the majority of people engaged in cleaning or babysitting are women) but also on "race" and social class inequalities, since it is usually vulnerable immigrant women who perform these tasks.

To analyze the effect of "income" on the variation of DEI, we could introduce in the first part of the questionnaire a question about the couple's monthly net income, with three income brackets: from zero to 2,500 euros; from 2,501 to 5,000 euros, and over 5,000 euros.

Furthermore, the "outsourcing" effect is taken into account by including a specific question in the socio-demographic section of the questionnaire (see the note on the attached questionnaire), asking for the gender of the person responsible for outsourcing.

|

A Only |

A Mostly |

A and B |

B Mostly |

B Only |

Outsourced |

|

-1 |

-0.5 |

0 |

+0.5 |

+1 |

XX/XY |

The fourth hypothesis concerns the potential asymmetric presence in the labor market (one person working full-time while the other is entirely dedicated to domestic tasks). Several single-income families experience asymmetric situations, which often lead to discussions and tensions.

The fifth hypothesis deals with the life cycle of a couple. There are at least two possible interpretations of this hypothesis. First, we will try to understand how domestic balances change in "young" and "older" couples, from the perspective of the duration of the relationship. In the second interpretation, we will study the differences that exist in young or adult couples in terms of the age of the individuals that make up the couples. The idea is to understand whether young couples may be more sensitive and, therefore, more attentive to these dynamics, in order to derive specific elements to guide subsequent proposals for action.

Data

In our model, data plays a primary role. We envision this tool as the outcome of various rapid survey methods used in the development world. We also want to design it with the flexibility and agility for rapid data collection.

The questionnaires will be administered to both individuals in the couple/family. The questionnaires will be anonymous, limited to reporting gender, age group, education level, the number of children, and the monthly net income of the couple/family.

At the margin of the questionnaire, and to capture subjective choices, we will include a question about subjective satisfaction with the current state of affairs. The purpose of this question is twofold: to understand the extent to which members of the couple feel that their aspirations and ideas are reflected in the current situation and to assess how this perception changes over time. It is conceivable that there are couples where an imbalanced situation in favor of one member is still considered satisfactory by that person. This may be due to cultural and social legacies. It would be interesting to assess changes in the medium to long-term following awareness and empowerment campaigns.

The responses obtained will depend on the respondent, i.e., they will presumably differ from partner A to partner B. Therefore, it will be necessary to compensate for possible cognitive and psychological distortions. One possibility is to assign the average value of the two responses to the family/couple.

The average of all the values found will allow us to establish an initial value at time T0. Periodic monitoring (biannual, annual) would then allow us to show the trend for the group, association, movement, or political party.

The use of the average is common practice in statistical inference. In the case of the DEI, because it requires subjective interpretations of each individual's use of time, the use of the average serves two purposes: to clean the data from the cognitive bias that each of us would introduce into the responses and to provide a sense of how aligned and aware the couples we are targeting are. In the first case, each of us is likely to attribute more domestic roles and tasks than our partner recognizes; it will also be interesting to understand how many of these self-attributions will overlap, i.e., are self-attributed to both partners. The other aspect has to do with how much individuals deviate from the average value, i.e., how much aligned the partners agree in recognizing each other's roles.

An Example

Assuming that, as a result of negotiations with the other party, you have agreed on a questionnaire with 100 questions, the responses from partner A would be as follows:

-1: 75 responses; -0.5: 5 responses; 0: 5 responses; +0.5: 10 responses; and +1: 5 responses – no outsourcing

In terms of percentages, this becomes:

-1: 0.75; -0.5: 0.05; 0: 0.05; +0.5: 0.10; +1: 0.05

Calculating DEI for partner A:

(-1) * 0.75 + (-0.5) * 0.05 + 0 * 0.05 + (0.5) * 0.10 + (1) * 0.05 =

-0.75 - 0.025 + 0.05 + 0.05 = -0.675 DEI value for partner A

Now, for the responses of partner B:

-1: 55 responses; -0.5: 5 responses; 0: 20 responses; +0.5: 10 responses; and +1: 10 responses – no outsourcing

In terms of percentages, this becomes:

-1: 0.55; -0.5: 0.05; 0: 0.20; +0.5: 0.10; +1: 0.10

Calculating DEI for partner B:

(-1) * 0.55 + (-0.5) * 0.05 + 0 * 0.20 + (0.5) * 0.10 + (1) * 0.10 =

-0.55 - 0.025 + 0.05 + 0.10 = -0.425 DEI value for partner B

The average value for that couple would be –(0.675 + 0.425)/2 = -0.550

Conclusions

The main purpose of an indicator like this is to serve as an advocacy tool for greater gender equality, starting from the domestic sphere and through continuous monitoring.

This indicator is designed for a specific audience, namely those groups, associations, movements, and/or political parties that take public positions in favour of gender equality. The DEI will allow them to demonstrate the consistency between their discourse, words, and concrete actions taken within their organizations to encourage participants (or sympathizers) in these groups to initiate (or continue and accelerate) a path of change towards true gender equality.

The DEI will be measured several times over time, because we firmly believe that the most interesting aspect is to see how (if!) the balance changes over time.

We strongly believe that a change in the domestic sphere (or social reproduction) is central to building a different and better world. In a society that has given a key role to indicators, it seems that accompanying grassroots lobbying efforts that involve men and women in achieving real time sharing within the domestic sphere, so that men take on their share of responsibility and free up women's time for various other uses, is an interesting proposal for discussion.

References

Catalano Weeks, A., (2022), The Political Consequences of the Mental Load, Harvard Working Paper, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/anacweeks/files/weeks_ml_oct22.pdf

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), 2012, Rationale for the Gender Equality Index for Europe https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/publications/rationale-gender-equality-index-europe

Eissler, S.; Heckert, J.; Myers, E.; Seymour, G.; Sinharoy, S; and Yount, K. M. 2021. Exploring gendered experiences of time-use agency in Benin, Malawi, and Nigeria as a new concept to measure women’s empowerment. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2003. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.134275

Field, E., Pande, R., Rigol, N., Schaner, S., Stacy, E., Troyer Moore, C., (2023) Measuring time use in rural India: Design and validation of a low-cost survey module, Journal of Development Economics, Volume 164, 103105, ISSN 0304-3878,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2023.103105.

Heckert, J., Quisumbing, A., Meinzen-Dick, R., Seymour, G., Malapit, H., Paz, F., Sinharoy, S., Yount, K. M., and Moylan, H., (2023), Developing a Women’s Empowerment Metric for National Statistical Systems, accessed on December 1st, 2023, https://www.ifpri.org/blog/developing-womens-empowerment-metric-national-statistical-systems

Hickman, W.; Kramer, B.; Mollerstrom, J.; and Seymour, G. 2023. Valuing control over income and time use: A field experiment in Rwanda. ICES Discussion Paper March 2023. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University. https://d101vc9winf8ln.cloudfront.net/documents/46102/original/Valuing_Control_Over_Income_and_Time_Use_A_Field_Experiment_in_Rwanda_by_Hickman_et.al.pdf?1679602724

Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE), (2010) Enquête Emploi du temps, https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2118074

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) (2020) Indice di Asimmetria nel lavoro domestico, https://www.istat.it/it/files/2022/04/3.pdf

Rodsky, E., (2020) Come ho convinto mio marito a lavare i piatti, Vallardi Ed.

Seymour, G., Malapit, H., and Quisumbing, A., (2020): Measuring Time use in Developing Country Agriculture: Evidence from Bangladesh and Uganda, Feminist Economics, DOI: 10.1080/13545701.2020.1749867

[1] Paolo Groppo, FAO (R), Member of “Ecofemminismo e Sostenibilità”; Marco D’Errico, Economist; Charlotte Groppo, CIO, Head of Gender Equality, Diversity and Inclusion; Clara Park, FAO Senior Gender officer; Costanza Hermanin, Political Analyst, European University Institute, Firenze; Laura Alfonsi Castelli, PhD Student Technische Universität, Berlino; Francesca Lazzari, Consigliere di Parità, Provincia di Vicenza; Marco De Gaetano, Economist, International Consultant; Sophia Los, Architect; Roberto De Marchi, Agronomist; Maria Paola Rizzo, FAO Land Tenure expert; Laura Cima, Ecofeminist

[2] https://unric.org/it/obiettivo-5-raggiungere-luguaglianza-di-genere-ed-emancipare-tutte-le-donne-e-le-ragazze/

[3] Héritier-Augé, Françoise, et Pascale Molinier, 2014. La valence différentielle des sexes, création de l’esprit humain archaïque, Nouvelle revue de psychosociologie, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 167-176

[4] https://unric.org/it/obiettivo-4-fornire-uneducazione-di-qualita-equa-ed-inclusiva-e-opportunita-di-apprendimento-per-tutti/

[5] Executive boards in case of organizations; other forms of leadership in case of informal groups (e.g. elders in a village).

[6] https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2022

[7] Rodsky, Eve. 2021. Fair Play: Share the mental load, rebalance your relationship and transform your life. Quercus publiching

[8] https://www.istat.it/it/files//2011/01/testointegrale201011101.pdf

[9] https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2123967#titre-bloc-3

[10] Weeks, Ana Catalano, 2022. The Political Consequences … op. cit. e Daminger, Allison et al., 2019. The Cognitive Dimension of Household Labor, American Sociological Review Vol. 84 Issue 4

[11] For the French-speaking public, we highly recommend Emma's comic (free to view), Fallait demander - Un autre regard Tome 2 (https://emmaclit.com/2017/05/09/repartition-des-taches-hommes-femmes /) which contains a specific chapter on mental charge

[12] There is the possibility that an activity x (or an index i) is partially carried out by both members of the pair. This is one of the most intriguing aspects of the data collection, as it will give the possibility of evaluating the self-attribution of skills and activities. It will then be necessary to calculate the average of the two partners' responses to arrive at a result that is free from distortions.

[13] Dalla Costa, M., 1972. op. cit.