River turns black after coal mine dam collapse next to rural communities and Hluhluwe-iMfolozi game reserve

An anthracite mine in rural KwaZulu-Natal which has operated for more than 30 years and has reportedly been involved in several controversies during this time involving water pollution, illegal mine expansion and water shortages in neighbouring rural communities, experienced a slurry dam collapse on 24 December 2021. Large volumes of potentially toxic and acidic coal-mine effluent have spilled into rivers flowing through rural communities and the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi and iSimangaliso wildlife reserves. Tony Carnie writing in the Daily Maverick Our Burning Planet has the story.

The Zululand Anthracite Colliery (ZAC), a major coal mine in KwaZulu-Natal, is under fire after at least 1,500,000 litres of polluted mine waste burst from a slurry dam and spread into the surrounding land and rivers.

According to the US-based Union of Concerned Scientists, mining and coal-washing operations produce highly acidic water pollution which can also contain toxic heavy metals such as arsenic, copper, lead and manganese.

Coal mining effluent pours out of a collapsed slurry dam at the Zululand Anthracite Colliery near Ulundi on 24 December, next to homes, before emptying into the Black Umfolozi River which flows through subsistence farming areas and the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park.

Though the dam collapse happened on 24 December, residents say some affected communities were not warned about the potential hazards until two weeks later. Conservation managers in the neighbouring Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park (HiP) were also led to believe that the spill was under control, only to discover a pitch-black plume of water flowing through the park several days later.

Now the mine’s owners have been ordered to expand the ground and surface water pollution monitoring points as far south as the Lake St Lucia estuary, where the Umfolozi River enters the sea.

According to the mine, a three million-litre dam collapsed on December 24, releasing an estimated 1.5 million litres of liquid coal slurry. Mine managers acknowledged that a newly installed slurry pond “end wall” had collapsed. Some of the pond waste had been emptied in November, ZAC said, also suggesting that the wall collapse was aggravated by heavy summer rains in the days leading up to Christmas.

Since then, large volumes of liquid coal mining waste have flowed into the nearby Umvalo River, which in turn feeds the Black Umfolozi River and the White Umfolozi River, which then drains into the sea and the Lake St Lucia estuary mouth.

So far there have been no confirmed reports of human, domestic livestock, fish or wild animal deaths further downstream, but aerial images taken last week show extensive pollution of the Black Umfolozi River inside the wilderness zone of the 96,000ha Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park. The park is one of the oldest game reserves in South Africa and is home to a significant population of black rhino and white rhino and other protected species.

Some residents fear the pollution has contaminated rivers, pans or groundwater used by isolated rural communities in the vicinity of the ZAC mine, located 25km from Nongoma and 40km from Ulundi.

In a letter to the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, and the SA Human Rights Commission, Okhukho resident Msizi Myaka called for a full investigation into why the slurry dam collapsed and whether a ZAC wash plant and slurry ponds were authorised in terms of environmental legislation.

Myaka said that many residents, including the Jahidada community, depend on the Umvalo and Black Umfolozi rivers for human and livestock drinking water.

“The incident happened on 24 December 2021, at around 2pm, and on 6 January (12 days down the line), ZAC had not communicated this incident with the affected homesteads and Jahidada community as per the requirement of good/best practice and legislation,” Myaka said.

Jahidada residents were not forewarned by the ZAC to take reasonable precautions, nor given Material Safety Data Sheets about the chemicals or metals released from the slurry dam, he said.

In a separate letter to the mine on 6 January, Jahidada community member Gaya Mchunu complained that: “As you know very well, we have only one drinking source — Umfolozi River. This water was polluted by ZAC, and Jahidada residents continued drinking from this source until now. We therefore feel that this was unethical and it compromised our health.”

He also requested a meeting with mine managers to discuss remediation measures, the provision of clean water to the Jahidada community and livestock and health checks for those who had drunk contaminated water.

The Menar group, which owns the mine, said it was not able to respond immediately to a list of questions sent by Our Burning Planet just after 2pm on Tuesday.

However, in a media statement on 6 January, mine officials said the ZAC was engaging with local community forums and structures to assess “possible damage caused to surrounding host communities” and to discuss resolution.

“On the 5th and 6th January 2022, ZAC management held meetings with the ZAC Community Forum structures through which the mine regularly interacts with host communities,” the statement noted.

The ZAC suggested that community leaders were “generally satisfied” with the manner in which the ZAC had handled the incident and it was working with relevant authorities “to ensure continued support for livelihoods and economic activities”.

In October 2000, a coal slurry dam in Kentucky, US, collapsed, contaminating hundreds of kilometres of rivers and streams with more than 1.3 billion litres of black sludge. Senior officials of the US Geological Survey said this slurry leak caused fish kills along 93km of the Sandy River and its tributaries and caused widespread disruption to local water supplies in downstream cities.

US Geological Survey chief scientist Dr Geoff Plumlee noted at the time that relatively little information was available about the composition and environmental impacts of coal slurry. However, studies of groundwater quality near other slurry dams showed elevated levels of sulphates, sodium, ammonium, iron, manganese, arsenic, chromium, zinc and cadmium.

While some fish kills could be attributed to the immediate gill-clogging effects of the slurry solids, the long-term chemical and acidic impacts were less clear.

Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife told Our Burning Planet that the ZAC informed conservation managers on Christmas Day that one of their slurry dams had burst and a significant amount of the coal slurry had been released into the Mvalo stream — which flows into the Black Umfolozi River.

“ZAC also informed Ezemvelo that the slurry had not polluted the Black Umfolozi River in that the slurry had only moved some 3km down the Mvalo stream and that they had already started cleaning up the spill.

“Despite the claims made by ZAC, park staff and tourists reported an accumulation of what appeared to be coal sediment on the edges of the Black Umfolozi River and its sandbanks. With this information, Ezemvelo alerted the Honourable MEC Ravi Pillay and senior members of his department of the risks the ZAC slurry spill posed to the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, the affected communities, downstream users of the Umfolozi River, and the estuary and lake within the iSimangaliso Wetland Park World Heritage Site.

“During this time, staff collected water samples for analysis. On January 5, park staff reported the presence of a large black plume entering the Black Umfolozi River from the Mvalo stream and was about to enter the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park.

“A voice note from one of the park rangers described the river as ‘pitch black, black, black’. Ezemvelo immediately appointed hydrological specialists with expertise in mining and mining operations who undertook a site inspection and collected water samples.”

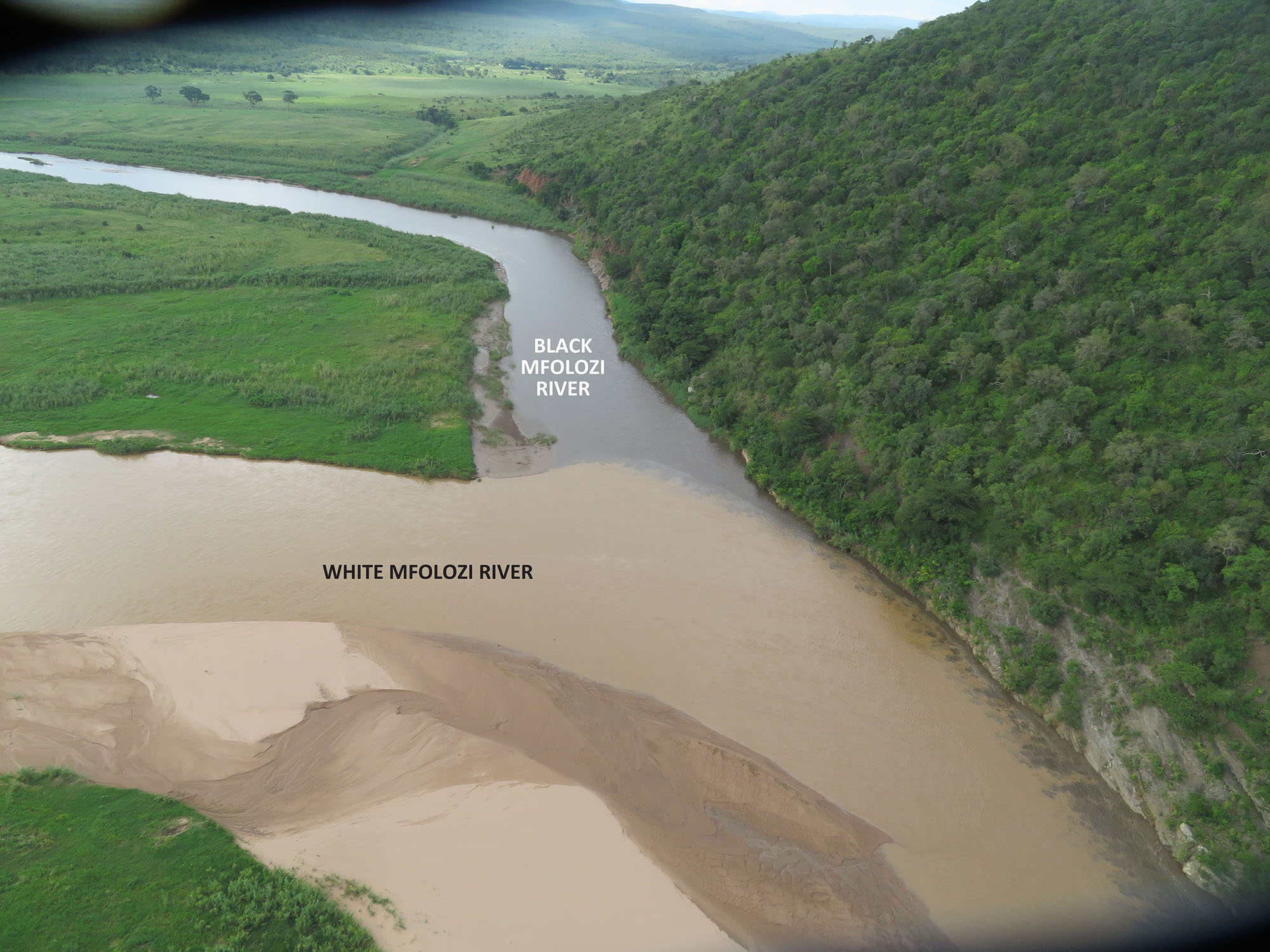

By this stage, the black plume had reached the confluence of the Black and White Umfolozi rivers. At this point, by comparing the colour of the two rivers, one could gain an appreciation of the magnitude of the pollution event, as the Black Umfolozi River was black in colour and had zero visibility for aquatic life. At the same time, the White Umfolozi River was its traditional light sandy-brown colour with moderate (normal) visibility.

“On the afternoon of the 7th, the black plume was seen to be leaving the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park. The Umfolozi River flows from the park through the Mpukunyoni traditional community to Mtubatuba town and thereafter flows into the iSimangaliso Wetland Park World Heritage Site.

“Ezemvelo is, at this stage, uncertain of the extent of the damage to the Umfolozi rivers and awaits the report from the hydrological specialists and the analysis of the samples taken. On receipt of this information, Ezemvelo will determine the way forward, including what remedial action needs to be taken. Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife will monitor the rivers and extend this to monitoring and sampling the groundwater to determine whether this critical resource has been contaminated.

“In the meantime, as a precautionary measure, Ezemvelo has put up signage not to drink tap water in the Mpila Camp. Bottled water is available for tourists.”

Ravi Pillay, the KwaZulu-Natal MEC for Environmental Affairs, said he had instructed his department to set up a Joint Operations Committee to investigate the matter and also told the ZAC to expand its water monitoring sampling points as far south as the iSimangaliso Wetland Park.

Pillay had also briefed the national ministers of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (Barbara Creecy), Water and Sanitation (Senzo Mchunu), Mineral Resources and Energy (Gwede Mantashe) and the mayors of the Zululand and Ulundi municipalities.

“The department officials have been on site to observe the clean-up processes and establish more facts about the extent of the spill and the potential threat to the public health and the environment.

“We note that ZAC mine has reported that no claims of damages, death or loss of livestock have been reported to them following the incident. While appreciating that report, we will, however, follow our own procedures and investigations,” Pillay said.

The anthracite mine has operated for more than 30 years and has been involved in several controversies during this time involving water pollution, illegal mine expansion and water shortages in neighbouring rural communities.

In 2014, the mine was issued with a “slap on the wrist” R497,000 fine by the KZN Department of Environmental Affairs for establishing three new coal mining shafts without seeking environmental authorisation.

It has also been embroiled in disputes over water pollution and drawing large volumes of water for mining and coal-washing operations, to the detriment of local communities, tourism and wildlife in the HiP.

Originally owned by BHP Billiton, the mine was later operated by Riversdale Mining and Rio Tinto before it was acquired in 2016 by the Menar group, founded by Turkish-born entrepreneur Vuslat Bayoğlu.

Menar has interests in gold and nickel in Turkey and Kyrgyz Republic, along with several coal and manganese mining operations in South Africa.

More recently, Bayoğlu’s group has been pushing to establish a new coal mine on the southern boundary of the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, Africa’s oldest wilderness area. DM/OBP

Language of the news reported

Copyright © Source (mentioned above). All rights reserved. The Land Portal distributes materials without the copyright owner’s permission based on the “fair use” doctrine of copyright, meaning that we post news articles for non-commercial, informative purposes. If you are the owner of the article or report and would like it to be removed, please contact us at hello@landportal.info and we will remove the posting immediately.

Various news items related to land governance are posted on the Land Portal every day by the Land Portal users, from various sources, such as news organizations and other institutions and individuals, representing a diversity of positions on every topic. The copyright lies with the source of the article; the Land Portal Foundation does not have the legal right to edit or correct the article, nor does the Foundation endorse its content. To make corrections or ask for permission to republish or other authorized use of this material, please contact the copyright holder.