By Chris Hufstader

After an audacious land grab by a foreign company, indigenous women in a remote Cambodian village struggle to regain their farms and sacred sites.

Sol Preng remembers vividly the day in 2012 when bulldozers unexpectedly arrived on her family farm.

“The company came and cleared away our cashew trees right before the harvest,” she says. “I lost four hectares of land and all my cashew trees.”

That would have been Preng’s third year of producing cashew nuts, and she was anticipating a $1,000 harvest. Instead, the 58-year-old lost her trees, her home, and worst of all, she says, “We lost our forest, which was an important source of food. We used to go there in search of mushrooms and other vegetables.”

Nearly everyone in Malik, an indigenous Toumpoun village in Ratanakiri province, was affected. The government granted an 18,952-hectare (46,432 acres) Economic Land Concession to a Vietnamese company called Hoang Anh Gia Lai, which planted rubber trees. The concession covered 400 of Malik’s 942 hectares.

The company destroyed rice fields, community forests, and burial areas, with no warning or consultation. It was a violation of Cambodia’s land laws as well as international laws designed to protect the rights of indigenous people to be consulted about development projects on their land.

Like Preng, Khwas Blov, 48, lost her entire 1.5 hectare cashew farm, plus her banana trees, chickens, and even her home. “My husband was away and I was alone,” she says. “I could not get everything out of my house before it was knocked down and everything destroyed.” She says she had to “just get out before I was run over by a bulldozer.”

“I still feel really angry,” Blov says.

When the dust settled, Blov, Preng, and others, like their friend Khwas Vin, got together to talk. “I was angry with the company, but I did not know what to do,” Preng says. “I wanted compensation for the loss of my cashew harvest and trees.”

Blov says they looked for help. They found the Highlander Association (HA), Oxfam’s partner that specializes in training indigenous people about human rights, and the local and international laws and regulations related to land and natural resources. Its director Dam Chanthy is herself a Toumpoun woman.

After a few meetings with HA, Blov says, “I started to go house to house to recruit women to work together to get our land back.”

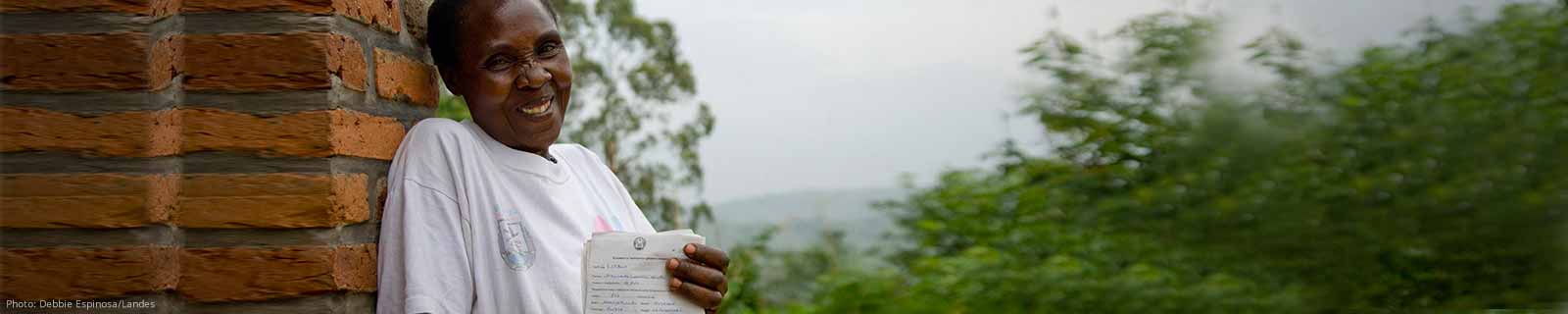

Vin and Blov are with Preng on her farm, a sparse field just outside Malik where she grows cassava and some vegetables. They are sitting in a small three-walled structure as the sun starts to set, and the sky takes on a faint rose color. Blov smokes a pipe and looks up at the evening sky.

She says they coordinated with non-governmental groups in Cambodia to research the company that destroyed their farms. They learned that the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency at the World Bank had invested US$16.4 million to a company in Vietnam linked to the Hoang Anh Gia Lai rubber plantation.

This opened up an opportunity: Malik and 16 other communities affected by the land concession filed a formal 36-page complaint to the World Bank in 2014. It detailed the loss of land, water sources, agricultural zones, and culturally significant “spirit forests” and burial areas. In 2015 and 2016 the Bank’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman visited the areas and began organizing meetings between the villages, government, and company. By 2017, “The company was ordered to pay compensation, and it had to stop clearing land owned by us,” says Vin. “They are now measuring the forest land, spirit forest area, and burial areas so they can be returned to the communities.”

At the end of March 2019, the provincial government of Ratanakiri announced that the company would return an additional 742 hectares of land comprising culturally significant “spirit mountains,” burial areas, and other environmentally sensitive water sources.

The communities are still negotiating compensation for their losses. So far, Vin says, the company has committed to “contribute buffalos for sacrifice ceremonies” so Malik and other villages can make amends to their ancestors, who they worship in spirit areas of the forest now destroyed. But they also need to discuss compensation for lost harvests and property.

Vin says the Highlander Association and other non-government organizations have provided essential training for women in Malik, such as “traditional land management practices, negotiation skill, lobbying tactics; like how to approach effectively engage with the company. Women’s rights, land rights, and our right to free, prior, and informed consent – it’s very important to know all this.”

Chanthy, who grew up near Malik, says the women here played a key role in the negotiations by taking a non-confrontational approach to their interaction with the government and company. But they remained firm, and looked to the future.

“These women understand the importance of land,” she says, “and the importance of having it for the next generation.”

Read the original Blog here

Going house to house

Following the money

Land is sacred