The government should establish proper pro-poor land reform instead of fiddling with the Constitution

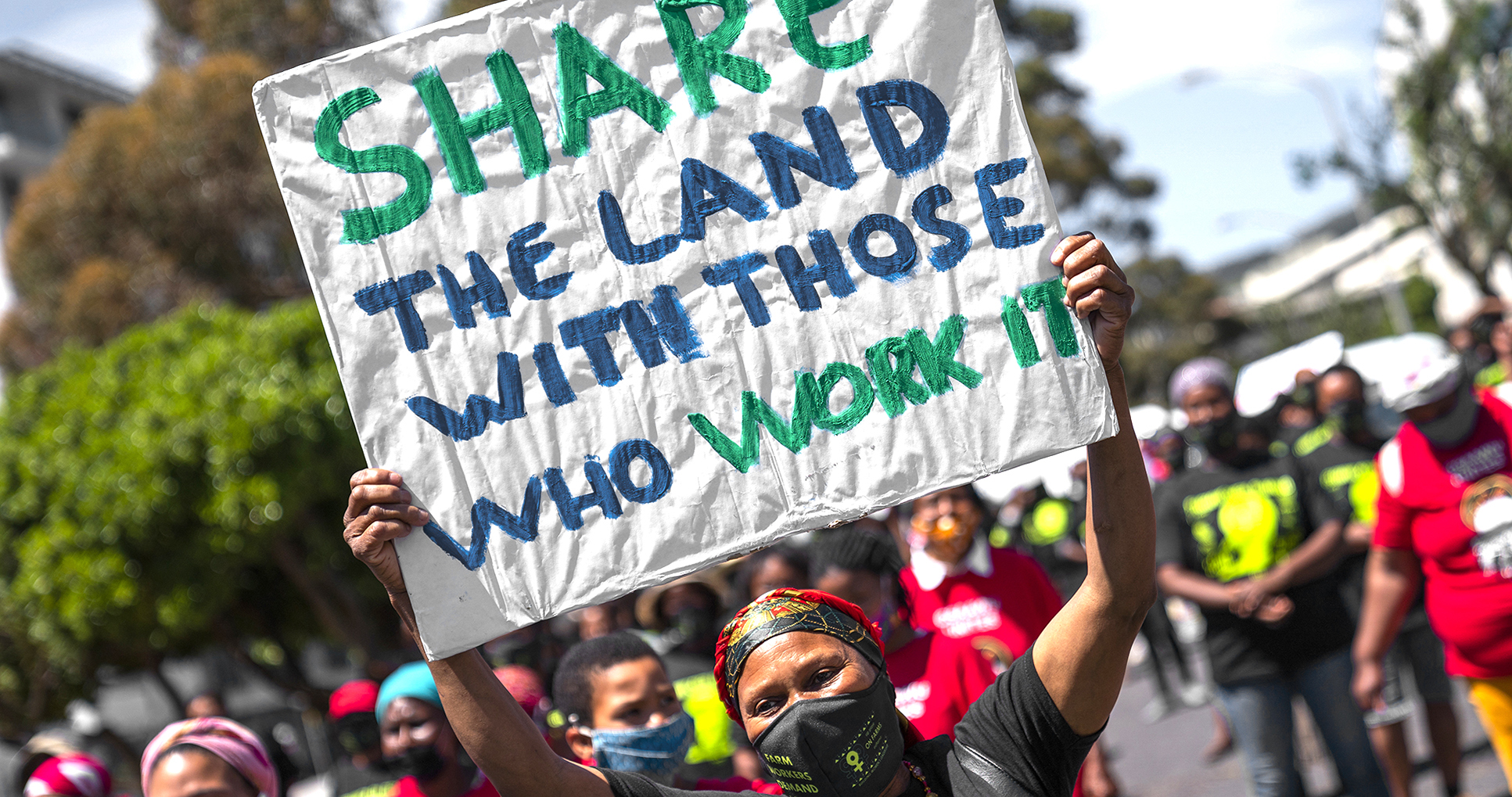

Gender equity is also key to land reform since women are under-represented and have not benefited from land reform in any meaningful manner. (Photo: newframe.com / Wikipedia)

By Farai Mtero, Katlego Ramantsima and Nkanyiso Gumede

15 Dec 2021 0

Policy gaps have provided fertile ground for elite capture of land reform, with urban-based business people accessing land ahead of the landless and land-poor.

After close to four years of government efforts and public consultation, a bid to amend the Constitution, supposedly to enhance the state’s powers to expropriate land for land reform purposes, has collapsed. On 7 December the ANC failed to garner the two-thirds parliamentary majority required to amend any aspect of South Africa’s Bill of Rights.

The process to amend Section 25 of the Constitution was, from the outset, characterised by a lot of political posturing and the pursuit of narrow party interests.

Various political parties, but mainly the EFF and the ANC, have sought to leverage the process to win favour in the light of widespread public disaffection with the present slow pace of land reform.

It would in fact have been a surprise if the bill had been passed, given that the EFF, which proposed the original land reform motion in 2018, holds a radically different position on what state custodianship entails and the role of expropriation in land reform to that held by the ANC.

The EFF has been calling for the nationalisation of land from the outset, while the ANC has adopted a more conservative approach — pushing for a system under which certain land is placed under state custodianship to be held on behalf of land reform beneficiaries.

These two positions have seemed irreconcilable from the outset and it was abundantly clear quite early on that the bill submitted to the National Assembly was never going to be passed.

Is amendment of Section 25 necessary?

Section 25 of the Constitution is widely associated with the property clause — and at times is seen as synonymous with the entrenchment and protection of private property rights; yet one of its strengths is that its provisions actually balance competing interests quite effectively.

For example, besides protecting private property rights, Section 25 expressly provides for equitable land reform and social transformation.

Section 25 (1) contains a deprivation provision that basically confirms property rights are not absolute and can be interfered with.

Sections 25 (2) and (3) focus on the general provisions or principles supporting expropriation and outline how expropriation should unfold; while Section 25 (4) provides that the public interest is not just limited to public property but “includes a nation’s commitment to land reform and reforms that bring about equitable access to all South Africa’s natural resources”.

Sections 25 (5) (6) and (7) are reform measures and provide for the three components of South Africa’s land reform — land redistribution, tenure reform and restitution.

In sum, alongside the protection of private property rights, Section 25 contains comprehensive measures on equitable land reform.

State custodianship: a step backwards

The recently rejected proposed amendment to the Constitution sought to introduce the principle of state custodianship to section 25 (5) of the Bill of Rights. This would have represented a step backwards in the realisation of equitable land reform and would have weakened the existing constitutional provisions on broadening access to land.

The rejected amendment gave prominence to the notion of state custodianship as a requirement for ensuring equitable access to land. The idea was that the broadening of access to land would require the state to be the custodian of certain land on behalf of citizens, who would then derive benefits from this land through the state.

Those supporting this idea of state custodianship argued that it provides the most reliable guarantee of security of tenure and allows for democratic land administration.

But there is evidence that contradicts such arguments in favour of state custodianship.

For example, there have been many evictions of land reform beneficiaries leasing land from the state. In the mining sector, where the state is the custodian of mineral rights, most local communities have not benefited from mining resources. In addition, land administration systems have remained weak and undemocratic in South Africa. All of which suggests that state custodianship is an ineffective way of ensuring equitable access as required by the Constitution

Realising equitable, pro-poor land reform

Equitable land reform is about more than expropriation, which is really just one among a number of instruments for land acquisition. In this regard, the most significant obstacle to the achievement of such reform is the lack of appropriate legislation to guide its implementation.

In 2018, an Expert Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture appointed by President Cyril Ramaphosa recommended the adoption of a Land Reform Framework Bill which would, among other things, spell out who should benefit from land reform; and what percentage of land should be allocated to different groups of landless and land-poor people, small-scale farmers, medium-scale farmers and large-scale farmers.

So far, resources have been concentrated in the hands of well-off groups; and the urban and rural poor have not benefited significantly from land reform. Policy gaps have provided fertile ground for elite capture of land reform, with urban-based business people accessing land ahead of the landless and land-poor.

A Land Reform Framework Bill would ensure that land and public resources are allocated more equitably so that different groups, including the poor, can benefit. Relevant policies like the yet-to-be-finalised National Beneficiary Selection and Land Allocation Policy could also enhance the equitable distribution of resources and avert elite capture of land reform.

The rapid release of strategically located state land to deal with landlessness, especially in urban areas where there is overcrowding, mushrooming informal settlements, and land occupations by the poor in desperate need of land, has become an urgent priority.

Gender equity is also key since women are under-represented and have not benefited from land reform in any meaningful manner.

In addition, in the wake of the legal and policy uncertainty created by the recent political contestation over the issue of expropriation and the direction of land reform in South Africa, investors are seeking clarity on the approach to be adopted so that they can make more informed decisions.

As a response to such issues, there is an urgent need to replace the outdated Expropriation Act of 1975 with an appropriate law of expropriation that is aligned with the Constitution. The 1975 Expropriation Act only provides for compensation at market value. The new Expropriation Act should be supported by a clear policy on compensation to guide policymakers in the determination of compensation.

In addition, the Land Court Bill needs to be finalised to facilitate the establishment of a new Land Court which will be modelled after the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA). The idea is that by focusing on less adversarial methods of resolving disputes, land reform-related disputes may be settled more effectively and efficiently.

The system for land administration is also in serious need of attention. The 2018 presidential advisory panel report recommended that land administration should be adopted as the fourth component of land reform, in addition to redistribution, restitution and tenure reform. This is important in the light of the collapse of land administration institutions, which have left an estimated 60% of South Africans without recorded land or property rights. There is also widespread tenure insecurity and evictions even on state-owned land.

The land reform budget remains very low, averaging less than 1% of the total national budget. Land reform is not prioritised. Ultimately, any large-scale, pro-poor land reform programme will require the government to go beyond policy rhetoric and commit sufficient public resources to this project. DM/MC

Farai Mtero is a senior researcher at Plaas who works on land reform and inclusive growth. His current research is on land reform outcomes and more specifically the extent to which South Africa’s redistributive land reform has been pro-poor.

Katlego Ramantsima is a researcher and PhD. student in the SARChI Chair in Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (Plaas) at the University of the Western Cape; and a research associate at the Society Work and Politics Institute (Swop), Wits University, investigating issues on land and wider impacts on poverty and inequality in South Africa.

Nkanyiso Gumede is a researcher at Plaas at the University of the Western Cape. He is part of a research team investigating equitable access to land for social justice.

Source

Language of the news reported

Copyright © Source (mentioned above). All rights reserved. The Land Portal distributes materials without the copyright owner’s permission based on the “fair use” doctrine of copyright, meaning that we post news articles for non-commercial, informative purposes. If you are the owner of the article or report and would like it to be removed, please contact us at hello@landportal.info and we will remove the posting immediately.

Various news items related to land governance are posted on the Land Portal every day by the Land Portal users, from various sources, such as news organizations and other institutions and individuals, representing a diversity of positions on every topic. The copyright lies with the source of the article; the Land Portal Foundation does not have the legal right to edit or correct the article, nor does the Foundation endorse its content. To make corrections or ask for permission to republish or other authorized use of this material, please contact the copyright holder.