By Rick de Satgé, reviewed by Emery Nukuri and Séverin Nibitanga, Director of the Land and Development Expertise Centre (LADEC) in Burundi

8 October 2021

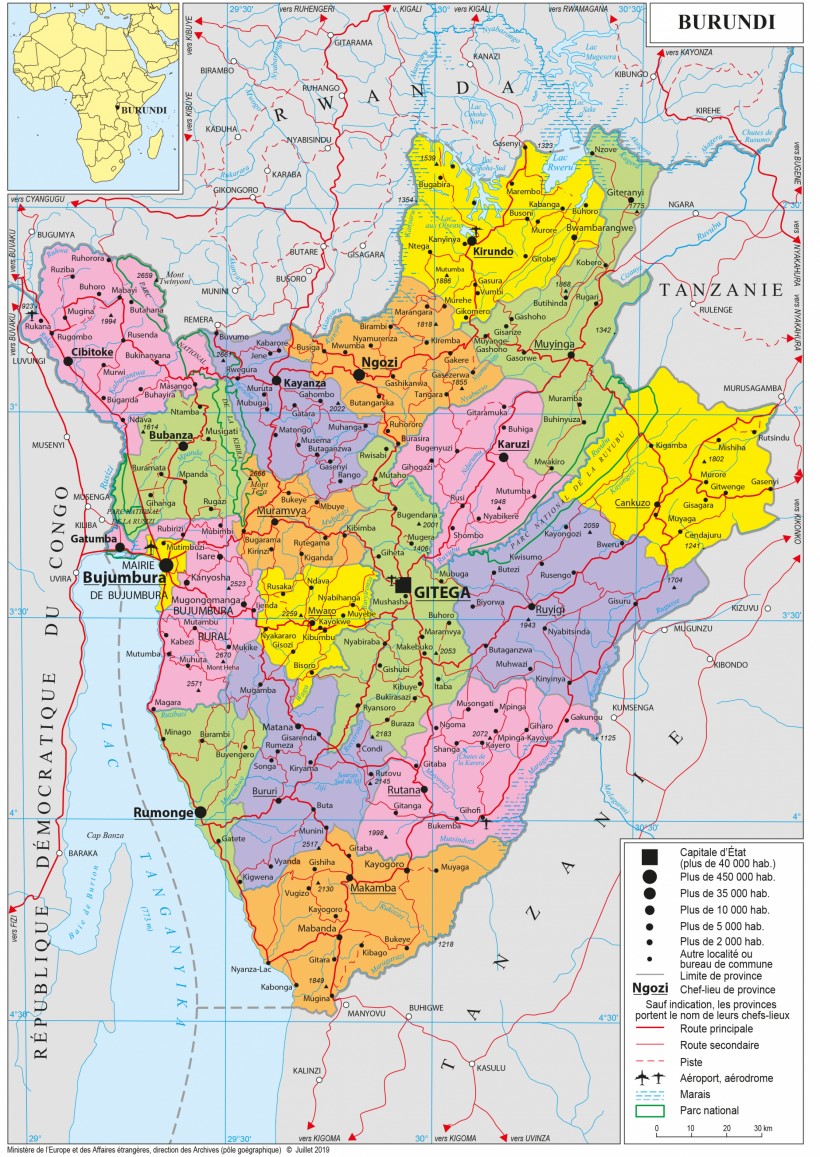

Burundi is a small landlocked country in East Africa, neighbouring Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Burundi has a total surface area of 27,840 km² of which 25,680 km² are land and 2160 km² are water. Burundi’s colonial and post-colonial history has been closely intertwined with neighbouring Rwanda and has been deeply scarred by periods of social conflict and civil war, contributing to the outflow and influx of large numbers of refugees.

Burundi faces enormous pressure on agricultural land given its very high population densities

Mahama Refugee camp for Burundian refugees in Rwanda 2015, Photo by UNHCR – Shaban Masengesho

Today, Burundi is one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 185th out of 189 countries in the 2019 Human Development Index. It is also one of the most densely populated countries in Africa with 435 persons per square kilometre with a predominantly rural population. The majority of rural households have access to less than half a hectare of farmland, while 90% of the population still rely on agriculture for their livelihood. The shortage of farmland puts scarce natural resources under stress as people are forced to cultivate land on steep slopes, or to encroach into protected areas1. In Burundi, women account for 55% of the workforce and do 70% of the farm work2.

Map of Burundi. Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères - Direction des archives (póle goégraphique) Juliet 2019

The country falls within a high rainfall zone but is experiencing an increasing frequency of extreme weather events. Burundi was affected by severe floods in 2006 and 2007, while in 2021 houses and land situated along the shores of Lake Tanganyika were inundated. The floods were followed by major droughts in 1999 - 2000 and 2005. Overall, 36% of the land is arable, but in 2018 Burundi was the lowest ranking country at 113 on the global food security index3. In 2019 the population was estimated to be 11.5 million people of which 13.3%4 were urban dwellers5. The combination of rural poverty, pressure on available land resources and mounting climate risk has begun to accelerate rural urban migration.

Historical backdrop

The pre-and post-independence histories of Burundi and neighbouring Rwanda are closely intertwined and conflicts in the two countries have also impacted significantly on each other, together with their neighbours in the Great Lakes region of Central Africa6. Both Burundi and Rwanda experienced oppressive German and Belgian colonial power and have suffered the protracted impacts of Belgian social engineering7. Both countries comprise two main communities – a Hutu majority and a Tutsi minority.

Different perspectives on the origins and social relations between and among Hutu and Tutsi peoples comprise a persistent thread woven through the contested history of the region. Historians caution against popular renderings of history which have “treated ethnic groups as if they were racial groups, biologically distinct, each with its own separate history”8. It has been argued that the commonly used “broad classificatory labels of "Hutu," "Tutsi," or "Twa" carry little explanatory value for historical understanding,” and that the history of Burundi is better understood through analysis of “multiple interactions and complex cultural processes” at local and regional scale.

While both Burundi and its neighbour Rwanda are commonly associated with intractable ‘ethnic conflict’, critics caution against such simplifications. In one view “Hutu, Tutsi and Twa do not even qualify as ‘ethnic groups’ in the anthropological sense of the word. They traditionally share the same monotheistic religion, the same language (Kirundi), the same customs and the same space: there is no Hutu-land or Tutsi-land… [However] in political terms the Burundian categories have nevertheless developed all the characteristics of ethnic groups”9.

The kingdom of Burundi has a long history as a monarchical state since the 16th century. However, multiple autonomous regions were only incorporated into the Burundi state during the reign of Ntare Rugamba in the early 19th century10.

According to Burundian customary law, the Mwami of Burundi was the master of all land in Burundi and the land was an inalienable collective property administered by the Mwami and his delegates: the Baganwa and the Batware11. The king or mwami allocated itongo – plots of land through a tightly regulated and hierarchical social system. The recognition of the eminent right of the Mwami was expressed by the payment of royalties by his subjects. These were the "inkuka" and the "umwimbu", to which were added gifts due to a new chief as a sign of allegiance, namely the "ingorore" and the "ishikanwa"12.

The kingdom fell to German colonial forces in late 190313 who capitalised on local rivalries to force agreement on the King. The Kingdom of Burundi was incorporated as part of German East Africa which included Rwanda and the mainland of present-day Tanzania. Following Germany’s defeat in World War 1, Belgium was given the mandate to administer Ruanda-Urundi14.

The Germans first, and then the Belgians after 1925, divided land into three categories: land subject to written law imported by colonial legislation registered in title exclusively for Europeans, land subject to customary law on which Burundians have “rights of occupation” under the control of the mwami as part of a system of indirect rule and state land that refers to ‘vacant’ land which the Belgians administered directly.

The post-colonial history of the region has been punctuated by episodes of violent social conflict and political instability associated with successive struggles to capture power and retain control of state resources.

Some understanding of the roots of the recurrent cycles of violent dispossession and displacement, later followed by peace accords that facilitate the return of refugees, often years later, is essential to enable a more informed reading of the complex and highly contested contemporary landscape.

Explanations of the conflict within and between these groupings highlight an intricate mix of elite contestation, clan rivalry, unequal access to land and economic resources due to clientelism and favouritism15. Social distinctions of relative wealth, influence and power were recast as ethnic divisions by the Belgian colonial administration, which enforced a system of indirect rule by actively promoting elements within the Tutsi minority, who were cemented as a ruling elite by being granted privileged access to land, economic opportunities, education and state jobs. These divisions have been entrenched as a consequence of social contestation in post-independence Burundi.

Since independence from Belgium in 1962, Burundi has experienced several outbreaks of violence. Significant inter-ethnic massacres occurred in 1965, 1969, 1972, 1988 and 1991. In Burundi power was initially held by a Tutsi dominated party which discriminated against the Hutu majority. In 1972 a Hutu revolt against Tutsi power killed thousands of Tutsis. The revolt was ruthlessly repressed by the Tutsi dominated military in what some analysts have characterised as an act of genocide, targeting Hutu citizens as well as Tutsis who shared the same political views, resulting in 200,000 – 300,000 deaths16. Many thousands more Hutu fled Burundi as refugees during this period.

Both Burundi and Rwanda experienced conflict in the 1990’s which reversed power relations in each country. Events in each country have had profound impacts on their neighbours. In Rwanda a Tutsi minority “suffered systemic discrimination and cyclical mass violence, which forced many into exile”17. In Burundi, the first Hutu president was assassinated by Tutsi army officers in 1993, precipitating a bloody civil war, waged between October 21, 1993 and December, 200618. This caused an estimated 300,000 deaths and displaced of tens of thousands, forced to leave behind their homes, land and livestock19 to find refuge in neighbouring countries.

The land and property owned and worked by those killed or displaced in the violence were redistributed both to Tutsi and some Hutu people who were members of the ruling UPRONA Political Party. Other land was redistributed to regional development companies promoting rice, cotton and palm oil production (SRD Imbo, Rumonge) which in turn issued concessions to members of the UPRONA party. In many cases conflict linked land and property transfers were officially endorsed in documents countersigned by state officials20.

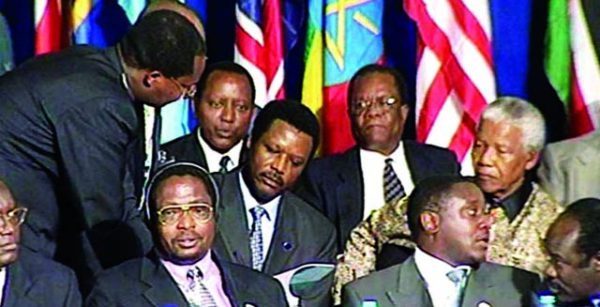

The Burundian Civil War was finally ended through a negotiated process culminating in the Arusha Accord in 2000. This sought to put in place an agreement of “a complex, consociational model of political power sharing based on ethnic quotas”21. A new constitution was drafted in 2005 and multiparty elections were won by a party formed out of the former Hutu rebel movement, the CNDD-FDD.

Nelson Mandela played a role in mediating the Arusha Accord which ended the Burundi Civil War, Photo by IWACU English News.

After the war, many refugees returned to Burundi and tried to recover their land. “It is estimated that up to half a million Burundians who fled genocide and war have returned to the country since 2005 – often to find the land they once called home occupied by strangers”22.

As negotiated in the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, Burundi established the National Commission on Land and Other Assets (Commission Nationale Terres et Autres Biens, or CNTB) in 2006. The Commission was given the monumental task of mediating between competing claims to land. In addition, Article 8(k) of the Agreement required that the Commission “must always remain aware of the fact that the objective is not only restoration of their property to returnees, but also reconciliation between the groups as well as peace in the country”23. At the same time those persons who had acquired the property rights of the displaced with state sanction, sought to protect these rights, or claim compensation in cases where property was restored to the original owners.

Initially the Commission sought to mediate solutions as it did not have the powers of a court of law. In 2014 the government of Burundi issued a decree to increase the authority of the CNTB. This attracted criticism by some and allegations that its new powers violated the terms of the Arusha Accords – that they were unconstitutional and usurped the function of the Courts.

The work of the CNTB was further destabilised by a protracted constitutional crisis in 2015 following President Nkurunziza’s decision to seek a third term of office, despite the Constitution restricting presidents to two successive terms. This triggered a renewed cycle of violence, assassinations and forced disappearances which resulted in some 152,000 people being internally displaced and a further 384,000 fleeing as refugees into neighbouring countries24.

In 2017 International Criminal Court approved the opening of a full investigation by the ICC Prosecutor regarding crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court allegedly committed in Burundi, or by nationals of Burundi outside Burundi, since 26 April 2015 until 26 October 2017. According to the ICC “the crimes were allegedly committed by State agents and other groups implementing State policies, including the Burundian National Police, national intelligence service, and units of the Burundian army, operating largely through parallel chains of command, together with members of the youth wing of the ruling party, known as the "Imbonerakure"25.

In June 2020 President Pierre Nkurunziza died suddenly in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic and former Hutu rebel leader Evariste Ndayishimiye took office as president.

Land legislation and regulations

Given Burundi’s conflicted and violent history which has triggered successive cycles of exile and return the government established a number of special commissions in charge of dispute settlement and reallocation of state-owned land to landless returnees. The first two commissions, created in 1977 and 1991, were followed in 2002 by the Commission Nationale de Réhabilitation des Sinistrés (CNRS.

The Commission Nationale Terres et Autres Biens (CNTB) was established in 2006 to restore property to two categories of dispossessed refugees – those fleeing violent reprisals in 1972, together with people displaced by the more recent civil war. The CNTB operates in all provinces and has parallel competences to the official first-instance courts for all conflicts involving a returnee.

At first the Commission sought to resolve conflicts through the “amicable settlement”, restitution and sharing of property. Despite having an initial record of significant success, reportedly settling 60% of cases through a mediated process, the remaining cases proved to be intractable. This, together with changing political circumstances, prompted the Commission to resort to arbitration. This followed legal changes and the relocation of the CNTB to the Office of the President.

New leadership of the CTNB took a much harder line in favouring those who were displaced and called for “unconditional restitution of land for the 1972 refugees”. At the legal level, the CNTB faced criticism for not taking into account the rights of those who received land from the State (with title deeds) or who became owners through the application of the rules of “acquisitive prescription” in which the property owner could prove open and undisturbed possession thereof for an uninterrupted period of 30 years. CTNB rulings were perceived by some to be arbitrary and discriminatory and equivalent to expropriation without compensation, restoring land rights of some, while dispossessing others.

In this regard Article 36 of the 2005 constitution of Burundi states that:

Every person has the right to property. No one may be deprived of his property except in the public interest, in the cases and in the manner established by the law and in exchange of a fair and prior compensation, or in execution of a judicial decision that has become final.

In its bid to restore land and property the institution was accused by some of “reviving ethnic hatred” and “aggravating land disputes”26.

In 2008 Burundi developed a land policy letter (lettre de politique foncière) followed by a Land Code (Code Foncier) in 2011. Generally, household land rights in the rural and peri-urban areas are regulated and managed through locally recognised practices and procedures. However, land in rural settings owned by businesses and companies is regulated by statute, together with some land in urban areas where title may be issued for properties.

In terms of Burundian land law any interference with the right to property must (1) have a legal basis (principle of lawfulness), (2) serve a legitimate public purpose or the general interest (principle of legitimacy) and (3) be proportionate27 in the sense that it must be examined whether it maintains a fair balance between the safeguarding of property rights and the requirements of the general interest (principle of proportionality)28.

The Burundian Land Code provides for compensation in the case of land expropriation29 but in practice the compensation is rarely awarded as provided by the law. It is often necessary to wait a period of one to three years to be compensated in the case of formal expropriation and several years of legal proceedings in the case of de facto or indirect expropriation30.

The Land Code sought to introduce land certificates and a decentralised system of land administration. Article 411 of the Land Code recognises the right of ownership exercised by virtue of a land title, a land certificate, an administrative title or a customary mode of acquisition. While the code legitimates land rights acquired under local land allocation systems, it requires that all such rights must be registered. It has sometimes proved to be difficult to validate the existence of these customary rights because of the lack of an official document. To address this problem 93 communes out of a total of 119 now have communal land services that issue communal land certificates to the population at affordable cost31. This increases the protection of household communal land rights, but civil society organisations note that overall, there has been a low level of state ownership for these reforms, many of which have been initiated by donors working together with local NGOs.

Conflicts of jurisdiction and financial considerations have often meant that the Land Titles Department does not facilitate the transformation of the communal land certificate into a land title. This raises questions about the legal standing of the communal land certificate. Efforts are still needed to ensure the success of the communal land services and to eliminate attempts to block the process.

A recent Law N°1/05 of 20 February 2020 fixing the registration fees in land matters now makes it compulsory for any buyer of a certified landed property to transform the land certificate into a land title. This transformation must take place within sixty working days of the signing of the deed of sale. In the case of the acquisition of land that is already certified, the buyer is required to register it immediately with the Land Titles Department, without going through the communal land service. This approach has the effect of depriving the communes of the power to manage transfers on certified land that has been sold. The approach also appears to contradict articles 408 and 410 of the Land Code, which provide for a special procedure for transforming a land certificate into a land title by means of surveying alone32.

Burundi has enacted other land related laws including the Environmental Code (2000), the Forest Code (2011) and the Mining Code enacted in 2013. A Code of Urban Planning, Construction and Housing was enacted in 2016. The 2011 Land Use Code was adopted by parliament in August 2016 but has still to be legally enacted. Consequently, the provisions of the outdated 1986 Land Code remain in force but are largely ignored by the state services and the population, which according to some analysts promotes disorder and anarchy33.

Overall, the greatest challenge facing Burundian land law is not so much the acceptability of its provisions, but the fact that it remains inoperable due to long delays in the signing of legislation approved by parliament into law which prevents implementation.

Land tenure classifications

There is enormous pressure on agricultural land given the very high population densities in Burundi. Law relating to land tenure in Burundi distinguishes between state and private land. State land includes forests and grazing land. However, this land is frequently managed by local administrations as a commons, with residents having rights to use natural resources. However, there are instances where wealthy people have had public lands privately allocated to them and hold exclusive rights to pasture or forested areas34.

Customary land authorities in Burundi which originally included the King (Mwami), chiefs or Princes (Baganwa), and deputy chiefs (Abatware) had largely disappeared by 1965, following the overthrow of the monarchy. This resulted in a major shift in the management of community land transactions which became managed within the family, rather than through customary institutions.

Family based land transactions are frequently recorded and witnessed by a local administrator. New systems have developed where people are issued local ‘actes de notoriete’. However, in many instances the local administrator issued authorisation without verifying the property boundaries and extent of the land transferred. The has limited the effectiveness of this system, while contributing to the possibility of future land disputes.

The Land Code developed in 2011 has promoted the piloting of decentralised land administration and the issuing of certificates.

Despite local systems of land rights management, unregistered rights lack formal legal protection. Access to land for household food production is often mediated through informal tenancy and sharecropping arrangements.

Overall, social conflict has deepened tenure insecurity and the registration of land rights remains far from the norm due to the complex and expensive process which must be followed for those seeking registered rights.

Land investments and acquisitions

While Article 13, section 4 of the Land Code states that “land for agricultural or livestock use cannot be transferred in full ownership to foreign natural or legal persons”, there are leasehold and partnership options available which can provide access to land by investors. The high level of pressure on scarce land resources coupled with political uncertainty has limited foreign investment in agriculture35. Cash crops occupy 10% of cultivated land and include coffee, tea, cotton, palm oil, sugarcane and tobacco, which are grown primarily by domestic producers36. In 2010 there were reported to be 10,000 ha allocated for industrial palm oil plantations. In Rumonge, the state redistributed land of people who went into exile, converting this into plantations for a new variety of oil palm. Once established, these plantations were redistributed to local elites37.

According to the US State Department since 2008, members of the executive branch have granted large discretionary exemptions to private foreign companies by presidential decree or ministerial ordinance in order to attract FDI38. However by 2019 Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Burundi was modest, totalling US$ 228 million in an environment where limits on foreign ownership and control have yet to be clearly established39.

The country has extensive reserves of nickel estimated to be around 285 million tons. However, these have yet to be exploited due to lack of electricity and rail infrastructure. Development of mineral resources has been reported as a government priority. By 2019 the value of Burundi’s gold, tin and rare earth minerals accounted for more than 50% of foreign currency earnings. Again, there remain concerns that mining primarily benefits well connected local elites40.

Women’s land rights

In Burundi women’s rights to inherit land face “the triple barriers of demography, tradition and the law”41. The elimination of traditional chiefs and related customary institutions that determined which family would receive land, and the extent of land to be allocated, has meant that “land grabbing has proliferated especially from widows, single women and land left by refugees"42.

Women's land rights remain precarious, photo by Counter Culture Coffee, Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

Customarily daughters have been excluded from inheriting land and while widows used to have a lifetime usufruct right following the death of their husbands, this is increasingly no longer recognised43. Widows often return to their parental home following the death of their husband. The combination of gender inequality, climate shocks, violence and political instability is closely linked to high levels of food insecurity in Burundi44.

While agricultural policy documents recognise the ‘central’ role of women and acknowledge their role as ‘principal’ agricultural producers, practical measures to advance women’s land rights and their role in the food system remain weak45.

Urban tenure issues

Active collaboration between UN-Habitat and the Republic of Burundi is relatively recent. Only 13.4% of the population is reported to be urbanised, with urban areas growing at 5.68% per annum. Bujumbura has a population of between 500,000 and 800,000, if the urban periphery is included. It is the largest city located on Lake Tanganyika and functions as a port for the country’s exports Burundi’s Vision 2025 seeks to accelerate rural-urban migration and urbanisation, so as to reduce pressure on arable land and provide non-agricultural urban employment opportunities.

However, the country currently lacks an overarching urban policy or a systematic spatial planning system. According to the Land Code expropriation is legally only possible for the benefit of the State and for another public person46. This is reported to restrict the expropriation of land for urban redevelopment purposes, where such land would be reallocated to private individuals. Economic pressures and lack of law enforcement in urban areas have contributed to the rapid growth of informal settlements. An estimated 39% of the city’s housing stock is informal47. Land allocation in the urban periphery has largely been through informal means. There is no legislation or policies which afford landless people and/or squatters rights to land and/or housing in Burundi. In urban settings titled property is largely restricted to the urban core.

Urbanisation is low at 13%, Photo by Dave Proffer, Creative Commons CC-BY. 2.0 license

Community land rights issues

Land scarcity and competition over land-based resources has been a key factor in driving up conflict risk. In 2012 it was estimated that rights to 15-20% of all land parcels were in dispute. Disputes over rights in land account for no less than 71.9% of all cases submitted to the courts and tribunals48. Contemporary processes to restore land to those who were dispossessed are in danger of creating further conflict. It is argued that those who were allocated land in transactions authorised by state officials should be eligible for compensation to recognise the investments they may have made in the land in the intervening period.

Public confidence in the CNTB and other state institutions responsible for dispute resolution and land rights management has suffered a decline, following perceptions of increasingly arbitrary resolution of disputes. Generally, people tend to rely more on local level dispute resolution institutions. Historically, these included the council of elder males known as the bashingantahe. However colonial and post-colonial policies served to undermine this institution, and in 2010 it was finally stripped of its functions as a local level dispute resolution forum49. Since 2005 state-sponsored local councils known as the conseil de colline involve both men and women and have been reported to be enjoying increased legitimacy50.

Community land rights of the Batwa remain precarious. The Batwa – a numerically small, marginalised minority forest people who live scattered across Burundi, Rwanda, the DRC and Uganda derive their livelihoods from hunting and gathering. In Burundi, the political rights of the Batwa were recognised and entrenched through the consociational model of representation adopted through the Arusha agreement and subsequently integrated into the Burundi constitution. However, in practice these legal protections remain weak51.

The weak land tenure rights of Batwa have been shaped by a long process of political exclusion and dispossession52. The ongoing treatment of Batwa land as ‘vacant’ by state actors and other ethnic groups have resulted in increased landlessness and poverty53. Advocacy groups have taken legal action to protect the land rights of members of the Batwa grouping following longstanding and unresolved land disputes with neighbouring communities54.

Land governance innovations

Burundi is one of 17 countries participating in the EU Land Governance Programme which focuses on structural problems of food insecurity and in the process seeks to address tenure issues and introduce the VGGT. Other initiatives include participatory approaches for identifying, delimiting, surveying and recording of public lands in Burundi to reduce conflict between the state and local communities. The Projet d’amélioration de la gestion et de la gouvernance foncière au Burundi (PAGGF) aims to improve the management and governance of public and private lands55.

Timeline - milestones in land governance

A detailed timeline is being prepared as a companion to this profile which draws on a variety of sources56. Some key dates have been extracted below.

1500 - The kingdom of Burundi is established.

1890 -Germany takes control of Rwanda and Burundi as part of its colonial holdings in German East Africa.

1916 - Belgium administers Burundi following Germany’s defeat in World War 1.

1933 -Belgian policy accentuates difference and ethnic identity of Hutu, Tutsi and Twa groupings in Burundi.

1962 - Burundi gains independence.

1966 - Monarchy abolished and Tutsi Hima elite capture power.

1972 -Mass killing of Hutu following a Hutu revolt is followed by mass exodus of refugees.

1993 - Assassination of elected Hutu President and six ministers by members of the Tutsi army plunge Burundi into years of civil war with massive casualties and displacement.

2003 - Arusha agreement ends hostilities.

2005 - New constitution.

2006 - Interim National commission for Land and Other Properties established to mediate and resolve land disputes related to refugees and internally displaced persons.

2007 - Pilot projects to localise land administration.

2008 - Land Policy Letter drafted.

2010 - Land Policy adopted

2011 - Law No. 1/13 of August 9, 2011 on Revision of the Land Code of Burundi ("Land Code")

2015 - Constitutional crisis as President Nkurunziza engineers a third term of office which provokes renewed violence and instability.

2017 - International Criminal Court opens an investigation

2020 - President Nkurunziza dies

Where to go next?

The author’s suggestions for further reading

The work of Filip Reyntjens is particularly valuable in clarifying the contested history of the Great Lakes region and the interlinked histories of the DRC, Rwanda and Burundi. Denise Bentrovato provides important insights in the challenges of interpreting history in post-conflict settings.

Mathjis van Leeuwen is a prominent researcher, who together with other authors has written extensively on Burundi and the Great Lakes region.

Haydee Bangerezako from the Makerere Institute of Social Research looks at the challenges of land rights management and restitution following decades of war and displacement. The Land and Enterprise Development Centre (LADEC) has published a series of reports in French on different aspects of land policy and administration.

A recent desktop review of land, housing and property law in Burundi undertaken by legal firm Webber Wentzel for the International Organisation on Migration is a valuable and up to date resource.

A search on the Land Portal will also identify recent documents of relevance to Burundi.

References***

[1] Baramburiye, J., M. Kyotalimye, T. S. Thomas and M. Waithaka (2013). "Burundi." East African Agriculture and Climate Change: A Comprehensive Analysis. Washington, International Food Policy Research Institute.

[2] Curtis, M. (2014). Putting small scale farming first: improving the national agriculture investment plans of Burkina Faso, Burundi, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Tanzania. Nairobi, Kenya, ACORD.

[3] Djita, R. and A. Hill (2019). "World Policy Analysis: Food Insecurity in Yemen and Burundi." Iris Journal of Scholarship 1: 37-47.

[4] Republic of Burundi, MEEATU, Descriptions of Burundi: Demographic and Socio-economic Aspects of Burundi, Bujumbura May 2012, p2.

[5] World Bank. (2019). " Population, total - Burundi." Retrieved 10 March, 2021, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=BI.

[6] See the DRC profile and timeline on the Land Portal for an example

[7] Mamdani, M. (2020). When victims become killers, Princeton University Press.

[8] Newbury, D. (2001). "Precolonial Burundi and Rwanda: Local Loyalties, Regional Royalties." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 34(2): 255-314. P. 271

[9] Reyntjens, F. (2000). Burundi: prospects for peace. London, Minority Rights Group International

[10] Newbury, D. (2001). "Precolonial Burundi and Rwanda: Local Loyalties, Regional Royalties." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 34(2): 255-314. P. 271

[11] Verbrugge, A., « Le régime foncier coutumier au Burundi », in R.J.R.B, n°.2, 2ème Trimestre 1965, pp.49-59.

[12] Nukuri, E., la protection constitutionnelle du droit de proprieté foncière en droit burundais, thèse, Faculty of Law, KU Leuven, 2019, p.58 ; DE CLERK L., « Note sur le droit foncier coutumier au Burundi », in R.J.R.B, n°.2, 1er Trimestre 1965, pp. 32-47.

[13] by the signature of the treaty of Kiganda between the Germans and the Mwami Mwezi Gisabo on June 3, 1903.

[14] Treaty with Belgium concerning her mandate over the Territory of Rwanda-Urundi, signed at Bruxellson April 18, 1923 and ratified by Belgium on October 20, 1924; https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/b-be-ust000005-0523.pdf

[15] Kohlhagen D., Land reform in Burundi: Waiting for change after twenty years of fruitless debate, http://www.globalprotectioncluster.org/_assets/files/field_protection_clusters/Burundi/files/HLP%20AoR/Land_Reform_Burundi_EN.pdf

[16] Lemarchand, R. (2011). 2. Burundi 1972: Genocide Denied, Revised, and Remembered. Forgotten Genocides, University of Pennsylvania Press: 37-50.

[17] Bentrovato, D. (2016). Whose past, what future? Teaching contested histories in contemporary Rwanda and Burundi. History can bite: History education in divided and postwar societies. D. Bentrovato, K. K. V and M. Schulze. Gottingen, V&R Unipress: 221-242.

[18] This civil war began with the assassination of Melchior NDADAYE, the first democratically elected Hutu President and ended with the signing of several peace agreements: The Arusha Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi of August 28, 2000, The Global Ceasefire Agreement of November 16, 2003 between the Transitional Government, established on the basis of the Arusha Agreement, and the CNDD-FDD movement, the Global Ceasefire Agreement between the Government and the Palipehutu-FNL of September 7, 2006 (as implemented since December 04, 2008), for more information see https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/projects/centre-des-grands-lacs-afrique/droit-pouvoir-paix-burundi/paix/.

[19] Kolhagen, D. (2011). "Land reform in Burundi: Waiting for change after twenty years of fruitless debate." Retrieved 1 August, 2021, from https://www.globalprotectioncluster.org/_assets/files/field_protection_clusters/Burundi/files/HLP%20AoR/Land_Reform_Burundi_EN.pdf.

[20] Odelag, OAG and G. Gatunange (2005). "La Problématique Foncière dans la Perspective du Rapatriement de la Réinsertion des Sinistrés.", Van Leeuwen, M. and L. Haartsen (2005). Land disputes and local conflict resolution mechanisms in Burundi, CED Caritas, Disaster Studies, Van Leeuwen, M. (2009). "Crisis or continuity? Framing land disputes and local conflict resolution in Burundi." Land Use Policy 27: 753-762.

[21] Bentrovato, D. (2016). Whose past, what future? Teaching contested histories in contemporary Rwanda and Burundi. History can bite: History education in divided and postwar societies. D. Bentrovato, K. K. V and M. Schulze. Gottingen, V&R Unipress: 221-242.

[22] Johnson, C. (2014). Burundi: New Land Law Raises Controversy, Global Legal Monitor [online] https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2014-01-27/burundi-new-land-law-raises-controversy/

[23] Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement

[24] Djita, R. and A. Hill (2019). "World Policy Analysis: Food Insecurity in Yemen and Burundi." Iris Journal of Scholarship 1: 37-47.

[25] International Criminal Court. (2017). "ICC judges authorise opening of an investigation regarding Burundi situation." Retrieved 2 August, 2021, from https://www.icc-cpi.int/pages/item.aspx?name=pr1342.

[26] Bangerezako, H. (2015). Politics of indigeneity: Land restitution in Burundi, Makerere Institute of Social Research.

[27] Article 36 of Burundian Constitution; African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Centre for Minority Rights Development (Kenya) et autres c. Kenya, § 219

[28] African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Communication 286 /2004 – Dino Noca vs Democratic Republic of the Congo, §146.

[29] Hilhorst, T. and N. Porchet (2012). Burundi: food security and land governance fact sheet. The Netherlands, IAS Academy on Land Governance and the Royal Tropical Institute (K IT).

[30] L’Ordonnance Ministérielle n°.720/CAB/304/2008 du 20 mars 2008 portant actualisation des tarifs d’indemnisation des terres, des cultures et des constructions en cas d’expropriation pour cause d’utilité publique, in B.O.B, 2008, n°.7 bis, p. 1331.

[31] Projet d’Amélioration de la Gestion et de la Gouvernance Foncière au Burundi (PAGGF), Feuille de route pour une approche nationale de sécurisation foncière systématique des terres privées au niveau décentralisé. Avril 2020. From http://www.ladec.bi/index.php/documents/recherches-enquetes/externe

[32] For more details see LADEC, Burundi, Loi N°1/05 du 20 février 2020 portant fixation des droits d'enregistrement en matière foncière. Quel impact sur la mise en œuvre de la gestion foncière décentralisée?, http://www.ladec.bi/index.php/health/burundi-loi-n-1-05-du-20-fevrier-2020-portant-fixation-des-droits-d-enregistrement-en-matiere-fonciere-quel-impact-sur-la-mise-en-oeuvre-de-la-gestion-fonciere-decentralisee

[33] LADEC, CEFOD, La Lettre de Politique Foncière, 9 ans après son adoption: état de sa mise en oeuvre, Juin 2019, pp. 14-20) (Translation : ,The land policy letter in Burundi, 9 years after its adoption: state of play of its implementation, June 2019, pp. 14-20.

[34] Hilhorst, T. and N. Porchet (2012). Burundi: food security and land governance fact sheet. The Netherlands, IAS Academy on Land Governance and the Royal Tropical Institute (K IT).

[35] Ibid.

[36] Seed Systems Group (2020). Strategy for the development of sustainable seed supply systems in Burundi. Nairobi.

[37] Carrere, R. (2010). Oil palm in Africa: Past, present and future scenarios, World Rainforest Movement.

[38] US Department of State. (2019). "2019 Investment Climate Statements: Burundi." Retrieved 8 August, 2021, from https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-investment-climate-statements/burundi/.

[39] Societe Generale. (2020). "Country risk of Burundi: Investment." Retrieved 18 March, 2021, from https://import-export.societegenerale.fr/en/country/burundi/investment-country-risk.

[40] Reuters staff. (2019). "Burundi's mineral exports overtake tea, coffee in hard currency earnings." Retrieved 18 March, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-burundi-mining-idUSKCN1UP1EK.

[41] Ndikumana, A. (2015). Gender equality in Burundi: Why does support not extend to women’s right to inherit land? Policy paper No 22, Afrobarometer.

[42] Kolhagen 2010. P7 in Serwat, L. (2019). A Feminist Perspective On Burundi's Land Reform. MsC in African Development, London School of Economics.

[43] Hilhorst, T. and N. Porchet (2012). Burundi: food security and land governance fact sheet. The Netherlands, IAS Academy on Land Governance and the Royal Tropical Institute (K IT).

[44] Djita, R. and A. Hill (2019). "World Policy Analysis: Food Insecurity in Yemen and Burundi." Iris Journal of Scholarship 1: 37-47.

[45] Curtis, M. (2014). Putting small scale farming first: improving the national agriculture investment plans of Burkina Faso, Burundi, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Tanzania. Nairobi, Kenya, ACORD.

[46] Article 411 of Burundian land Code: “The right of ownership exercised by virtue of a land title, a land certificate, an administrative title or a customary mode of acquisition, may be expropriated for public utility to the benefit of the State or any other public person, subject to the payment of a fair and prior compensation”.

[47] IOM and Webber Wentzel. (2020). "Burundi HLP Profile." Housing, Land and Property Mapping Project Retrieved 8 August, 2021, from https://www.sheltercluster.org/resources/documents/burundi-hlp-mapping.

[48] LADEC, CEFOD 2019) RCN justice et démocratie, Statistiques judiciaires burundaises, rendement, délais et typologie des litiges dans les tribunaux de résidence, Bujumbura, décembre 2009, p. 25

[49] De Juan, A. (2017). "“Traditional” Resolution of Land Conflicts: The Survival of Precolonial Dispute Settlement in Burundi." Comparative Political Studies 50(13): 1835-1868.

[50] Hilhorst, T. and N. Porchet (2012). Burundi: food security and land governance fact sheet. The Netherlands, IAS Academy on Land Governance and the Royal Tropical Institute (K IT).

[51] Vandeginste, S. (2014). "Political representation of minorities as collateral damage or gain: The Batwa in Burundi and Rwanda." Africa Spectrum 49(1): 3-25.

[52] LADEC (Serwat L. and Nibitanga S.). Land reform and dependency among Twa in Burundi (2019), p. 23.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Vital, B. and A. J. Pierre (2011). Ethnic and Racial Minorities and Movement Towards Political Inclusion in East Africa: The Case of the Batwa in Burundi. Towards a Rights-Sensitive East African Community, Kituo cha Katiba: Eastern Africa Centre for Constitutional Development: 126.

[55] Larbi, W. (2018). The VGGT and the framework and guidelines for Land policy in Africa (F&G): Versatile tools for improving tenure governance. World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. Addis Ababa, FAO.

[56] Mthembu-Salter, G., E. Berger and N. Kikoler (2011). Prioritizing Protection from Mass Atrocities: Lessons from Burundi. New York, Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect, FIDH. (2016). "Burundi conflict: A timeline of how the country reached crisis point." Retrieved 11 March, 2020, from https://www.fidh.org/en/region/Africa/burundi/burundi-conflict-a-timeline-of-how-the-country-reached-crisis-point.

Authored on

02 October 2021