It’s not unusual for children to leave home when they become adults: it is rarer, though, that they come back to invigorate the communities they grew up in with new ideas and services.

That, however, is exactly what is happening in indigenous territories throughout Indonesia. It is called “Homecoming”, although it is a far cry from the more familiar Western use of the term that involves high school sports events and prom dances.

These “homecomers” build schools, successful farms, and sustainable tourism destinations for the benefit of their indigenous communities as well as themselves. The result is an influx of income, but also renewed protections for traditional lands and cultures.

It all started a few years ago at a large national gathering of the youth wing of Indonesia’s Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN).

“They talked about the problems in the communities, the conflicts and other things, and they came up with the idea: ‘We have to go back home and take care of our territories’,” Mina Susana Setra, AMAN’s deputy secretary general, said in an interview with Tenure Facility.

A large motivation behind the plan was to ensure the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ traditional knowledge, which, crucial though it is to environmental survival in forest areas, is in danger of being lost to unfettered modernisation and development.

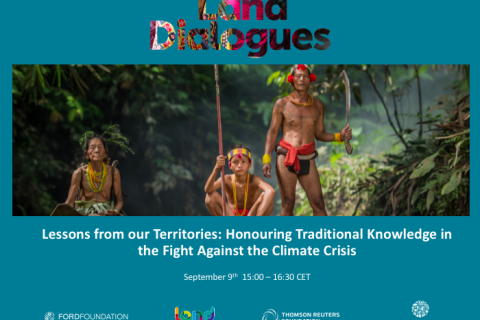

The threat is to be the subject of the next Land Dialogues webinar on September 9, “Honouring Traditional Knowledge in the Fight Against the Climate Crisis”. Setra will be one of the panellists at the webinar, which is hosted by Tenure Facility, Land Portal, and the Ford and Thomson Reuters foundations.

Perhaps the most immediate success of the Homecoming Movement has been the establishment of indigenous schools in various parts of Indonesia, which has as many as 70 million indigenous people out of the countries’ 276 million total population.

There are now 82 such schools — and created only since 2016. They do not replace formal education, but rather instil in the children who attend their indigenous culture. Pupils range from kindergarten age to as old as 17.

“The schools have specific curriculums to understand the knowledge of the elders, how to manage other traditional knowledge, how to manage their territories and these kinds of things,” Setra said, adding that this may include dance, music, and swimming.

“The goal is to ensure transmission of knowledge of the Indigenous communities,” she said.

The schools are not formally recognised by the Indonesian authorities but have been noted to the extent that they received an award from the Ministry of Home Affairs.

“They were amazed by how these young people returned (from the cities) and establishes these schools,” Setra said.

AMAN, which is affiliated with Tenure Facility, has supported some of the Homecoming Movement projects financially, but a lot of them are sole initiatives.

TURNING THE SOIL

Over the past two years or so, meanwhile, many homecomers have gone beyond education, turning to agriculture. They have created organic and sustainable farms that help their communities gain food security, protect the lands, and provide an economic boost.

These are not small allotments, but large, well laid-out plots of vegetables such as chillies, cassava , cucumbers, and local cabbage.

In one example — in Gowa province of South Sulawesi — returning youth have planted a picturesque herb farm that goes well beyond its beauty. It is an incubator for traditional medicines, with seeds brought in after gathering knowledge from elders and other indigenous villagers.

As a potentially lucrative spin-off, some of the farms have tapped into the burgeoning eco-tourism sector. Wooden cottages perch above the growing plots with spectacular views of mountains, forests, and valleys.

It is all part of Indigenous Peoples managing their own territories for the benefit of themselves but also of the wider world. And it can be lucrative.

Setra has calculated that returning youth groups in North Sulawesi and West Kalimantan (which are over 1,500 km apart, indicating the broad sweep of the movement) have earned up to $25,000 from each of their harvests — a lot more than they would have brought in working in Indonesia’s cities.

Indonesia has a net national income per capita of less than $3,500, according to the World Bank.

Most of the homecomers moved to the cities for education, rather than for work. But after schooling, finding a job with liveable income is very hard, which is part of the motivation for returning.

But it is far from being all about money. The youth realise there is an existential need for them to support their communities and their traditions.

It is, Setra said, primarily about contributing to the community, defending it, and managing its territories.

This piece was originally featured on the Tenure Facility's website