Published on 1 October 2024

Key facts: Urban TenureBrowse all

Escaliers Antaninarenina towards Ambondrona, Madagascar, photo by Andoniaina Nambinintsoa, license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

By Rick de Satgé, reviewed by Prof. Alison Todes, School of Architecture and Planning, The University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Urbanization patterns and land governance challenges in the global South are shaped by a complex interplay of forces, including climate change, demographic shifts, inequality, conflict, displacement, and migration. This issue page explores these dynamics and their impacts on cities, informal settlements, and tenure security across Africa, Latin America, Asia, and other regions.

Key concepts and terms

Colonial influence

It is worth reminding ourselves how the world we live in has been completely redrawn over the last 300 years. In 1700 there were just 600 million people living on the planet. Between the 16th and 19th centuries globally significant social and demographic changes resulted from slavery, colonial conquest and dispossession. Some 12.5 million people indigenous to Africa were enslaved and forcibly transported to the Americas. The geographies of pre-existing polities and their territories were erased as colonial powers contested with each other to grab land and established new states with new boundaries. Colonial control took different forms depending on the coloniser and the continent and in some instances dates right back to the mid 15th century.

The urban periphery

There are numerous forces at work reshaping cities and influencing the forms of urban growth. These reflect diverse urban histories and development trajectories. However, there is a general trend which is emerging: that increasingly we live in “the age of the urban periphery”.1 In the global South it is common to identify the urban periphery as a place of poverty and marginalisation. However recent research on post-colonial suburbs2 reveals how the urban periphery can become a zone of opportunity for increased middle-class occupation and housing construction. As cities expand, much of this is concentrated along the urban edge, while simultaneously there may be transformations within the urban core, either through densification or gentrification.

Urbanisation and planning

Since the 1950’s the rate of urbanisation in the global South has been much faster than in the global North.3 It has been forecast that by 2050, three billion people and half of all urban dwellers will live in informal settlements worldwide.4 By 2020 seventy of the hundred largest urban agglomerations, ranked by the population of the core city, combined with its settled periphery, were in the global South.5 Goal 11 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) seeks to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. The SDG committed to an urban paradigm shift including acceptance and inclusion of informality, density and environmental priorities. This runs counter to “50 years of anti-urban bias in development policy.”6 For example, as recently as 2013 84% of governments in less developed regions pursued anti-urban policies, seeking to limit urban migration.7 However, significant concerns remained around some of the assumptions underpinning the International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial Planning, adopted by UN Habitat in 2015. Critics asked whether the New Urban Agenda (NUA) had forgotten major critiques of past planning? These argued that “planners do not grasp the complex dynamics of contemporary urban change”.8 There were also concerns that the NUA assumed institutional and regulatory capacities of the state and local government which did not exist across much of the global South.9 While city planning is supposed to be guided by SDG 11, it remains a contested space. There are examples of inclusive planning practices which recognise the needs of the urban majority, but these frequently are confronted by the profit and revenue generation imperatives associated with “speculative urbanism”. This is focused on high value land deals and megaprojects such as Eco-Atlantic in Lagos or plans for Kigali, the capital of Rwanda.

These initiatives reflect elite aspirations to create ‘world class cities’ and fail to prioritise the needs of the poor and marginal.10 In many African contexts, systems of revenue generation from property taxes, regulations and fees are not properly in place. Many city administrations lack the capacity to implement these systems, so the local government frequently lacks a reliable source of revenue to fulfil its functions. This has contributed to the push to institute mechanisms for land value capture (LVC) and to opt for the kinds of urban development projects which provide a source of revenue. Where cities succeed in generating revenue, it remains to be seen whether this will be accompanied by targeted reinvestment in disadvantaged communities. A recent study of land value capture in Sao Paulo, Brazil indicates how if mismanaged this can concentrate “an enormous amount of resources within the city’s wealthiest areas, thereby strengthening socio-environmental disparities.”11

Global demographics

Demography plays a key role in shaping urbanisation and the future of cities in different settings. In 2023 about 2% of the global population was under 15 years of age, while 10% was over 65 years of age. There are major differences between the demographic profiles of countries in the global South and North. In Africa some 40% of the population are below 15 years, while less than 3% are above 65. By contrast Europe has an aging population with more people aged 65 years and above than those aged 15 years or less.12

In 2022 the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the UN predicted that:

- The share of the global population aged 65 years or above will rise from 10% in 2022 to 16% in 2050.

- The global population aged 60 and above is projected to double by 2050, reaching 2.1 billion.13

Factors driving urbanisation and migration

Across the globe millions are on the move for different reasons. The majority end up in urban areas, either in the global South or North. Diverse economic and social factors impacting on life in rural areas are driving this movement. Many are economic migrants seeking a better life. Others are refugees escaping conflict and persecution. In 2019 UNHCR reported that more than 70 million people had been forcibly displaced worldwide. UNHCR’s 2023 planning figures projected that the number of internally displaced people would rise to 117 million, of which 52% are located in Africa and the Middle East. According to the 2023 World Development Report approximately 184 million people lack citizenship in the country in which they live. Of these, some 37 million are refugees.14

In 2021 the World Bank estimated that climate change could trigger the internal migration of 216 million people by 2050.15 Clearly climate change is just one factor driving migration, and it often interacts with other factors like poverty, conflict, and political instability.

Overall there is no consensus on how climate change will impact on international migration.16 A recent prominent example highlights how fundamentally different conclusions can be drawn from the same data. The Groundswell model developed by the World Bank forecast increased climate mobility in African countries experiencing accelerating global warming.17 However the follow-up Africa Climate Mobility Model based on a similar methodology, forecast the opposite.18 To date, qualitative studies suggest that adverse environmental conditions primarily affect internal rural-urban migration rates, rather than driving cross border migration.19

Making sense of the factors influencing displacement and migration is context specific. It also requires a thorough understanding of the histories shaping space and place 20which must factor in the “deep differences between cities and regions”.21

Urbanisation and land governance

There is a debate in African cities about how much urbanisation is really happening, which centres on how ‘urban’ gets defined. Does it reflect population concentration/density or the predominance of non-agric economic activity? Depending on the metrics selected estimates can vary a lot. Also, some of what is sometimes measured as urbanisation reflects the inclusion of areas on the urban edge and perhaps growing density there. This is not necessarily the same as movement to cities/towns.

Land governance systems struggle to keep up with large scale and rapid change. Existing systems are premised on predictable and stable futures and are often insufficiently agile to adapt to change. Despite the proliferation of data worldwide, both global and local futures are characterised by high levels of uncertainty and hard to predict dynamics of change. Irrespective of their location, large cities and their peripheries are highly dynamic spaces. In the global North, the impacts of the Covid 19 pandemic continue to have major consequences for urban management. The persistence of hybrid and remote working has sharply devalued urban commercial real estate. As a consequence, municipal budgets are under pressure as tax revenues based on property values shrink. These linkages have recently been described as an “urban doom loop.”22

Across the global South, cities are constantly being reshaped by the flow of rural dwellers and cross border migrants moving into urban areas in response to locally specific push and pull factors. In the African setting urban expansion frequently encroaches on rural land under customary tenure systems. This may result in conflict over changing land uses while creating opportunities to access land and housing in less regulated spaces.23

Once in the city people do not necessarily settle and remain in place. There is often significant mobility among the urban population, as they seek to improve their foothold in the city and access better located land, closer to livelihood opportunities. Others, often, but not exclusively those who are better off may choose to move outwards to the urban periphery to access better and cheaper land for housing. Overall there is a huge physical expansion of cities which is underway.

Urban dynamics are complex and sometimes counter intuitive. Where the primary driver of urban development is based on the calculus of financial investment and returns on capital, this suggests that the poor will be excluded from well-located land. However, at the same time there are examples like Johannesburg where there are dense informal settlements and reoccupation by the poor of run down and derelict central city areas. The high population densities with many people sharing rooms, means that the combined ‘rents’ people pay to those who have taken control of these buildings are actually very high when calculated in rental charges per square metre.

In other cities like Mogadishu, which experience conflict and social upheaval, there are instances where the poor have managed to access better located land with development potential. However they are at risk of eviction, once a social order which favours elite interests is restored.24

Climate change and urban land governance

City geographies and tenure arrangements are increasingly impacted by climate change. The combination of floods, droughts, fires and heat waves can be acute in and around large cities, particularly where the majority of the population live in informal settlements and on land poorly suited for settlement. 25

As the map highlights above numerous coastal cities are threatened by rising sea levels. Chart: The cities most threatened by rising sea levels | Statista

Climate change creates additional challenges for urban planning and land governance. It renders life in poorly located human settlements increasingly precarious. In these settings there may be temporary advantage, but little long-term value to be gained from registering land and securing tenure. Such land has little chance of appreciating from a ‘dead asset’ into a capital that, theoretically, can be leveraged through registering a right. 26

Globalisation, migration and tensions in the city

There has long been a connection between globalisation and migratory population movements. This is accelerated by the increase in forced migration and a surge in the number of people seeking to escape crisis and turmoil in their home countries. “Migration is … not a smooth or painless process. It may cause social dislocation and instability, sometimes in both places of origin and destination”.27

Undocumented migration is increasingly a source of social and cross-cultural fears and tension. Gallup’s Migrant Acceptance Index for 2019 highlighted mounting global intolerance of migration. The World Values Survey (2017-2020) found that 49% of those surveyed feared that immigration would lead to social conflict in their country, while just 28% disagreed.28

The largest drop in tolerant attitudes was in Latin America, where several countries had experienced a large influx of refugees from Venezuela. Tolerance was also found to have fallen in several member states of the EU.29 In 2015 alone there were 1,822,000 illegal crossings into the European Union.30

This has led to the rise of nationalist/ anti- immigration political formations in both the global South and North which seek to severely restrict both the access and the rights of economic migrants and refugees. Examples range from South Africa to Belgium.

The Global Compact on Migration (GCM) and the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) identify the need to ‘promote evidence-based public discourse to shape perceptions of migration’.31 Evidence suggests that Europe will be significantly short of labour for at least the next 25 years.32

This reflects the ballooning numbers of retirement age adults coupled with diminishing birth rates. Projected demographic changes should provide a strong argument to enlarge formal migration opportunities. However public sentiment can be immune to evidence and influenced by other narratives. Currently mounting political intolerance in much of Europe and North America is throttling legal immigration avenues. This fuels an expanding market for human traffickers and migrant smugglers. These irregular channels place undocumented migrants at increased risk. The IOM’s Missing Migrants Project has recorded 63,858 people who have died in the process of migration towards an international destination since 2014.33

A vicious cycle

A squeeze on migration also has major economic implications for sending countries in the global South. Currently remittances from relatives in the diaspora represent a critical source of finance for many African economies. In 2022, West Africa alone received nearly $34 billion in remittances. The value of these remittances was more than double the amount of Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) combined.34 As economic benefits are captured by predatory and authoritarian regimes and southern opportunities shrink, so the push factors propelling South-North migration increase.

Southern urbanism

Southern urbanism is full of vitality and vibrancy, shock and disorder, spontaneity and fluidity. It is rife with pains, histories of injustice, grand dreams and colossal failings.35

Unlike cities in China, parts of Asia and Latin America, many African cities lack a developed industrial base. Diverse economic ecosystems have developed in which the informal sector plays a significant role. This is complemented by the service sector, the public sector and remittances from migrants in the diaspora. The ways in which informal and formal economies intersect within the urban ecosystem impacts on land use and tenure, housing and services as well as environmental management.

Land, housing and tenure

Many cities in the global South were shaped for a period by the intervention of colonial planners. In some cases this intervention had long-term impacts, while in others the colonial imprint was soon erased.

In the post-colonial period, cities in the global South have all grown rapidly, although there remain debates about how urbanisation rates are measured. Much urban settlement has been informal and unplanned. While there are significant variations, urbanisation has often accelerated at a speed which quickly outstripped the already limited state capacity for urban planning and regulatory control. UN Habitat has described how unmanaged urbanisation has contributed to:

- “the occupation of empty lots and self-construction of housing in public, communal and private land;

- the unlicensed subdivision and sale of private, communal, and public land by speculators;

- the development of irregular and/or extra-legal public housing projects;

- the unauthorized subdivision of previously legal plots for the construction of additional buildings outside of existing codes and plans;

- the occupation of riverbanks, reservoirs, mountain sides, and other environmentally protected areas;

- and the occupation of public spaces such as streets, pavements, and highways”.36

Revenue sources for cities are often irregular and inadequate. Given this context it is costly, legally and technically challenging to provide basic services to all residents. Land ownership in the cities across the global South remains fragmented and contested. In many African countries, as the footprint of cities has expanded hugely, so urban areas have encroached on land held under customary tenure systems. The pressures of land allocation for urbanisation have often distorted customary tenure norms, creating opportunities for traditional authorities to make land available to outsiders for a fee.

Favelas – informal housing in Latin American cities are frequently built on public land which is not zoned for housing. There are also examples where dwellings are built on privately owned land. This land may be occupied without the owner’s consent, or access obtained through informal land sales and undocumented transactions.

The prevalence of undocumented and contested ownership creates obstacles when cities seek to implement large-scale development projects, or infrastructure improvements. In recent decades, some governments in Latin America have implemented programmes to formalize land tenure in favelas through land titling programmes. These initiatives are also linked to the upgrading of informal settlements, where the state provides basic infrastructure and services in exchange for some degree of regularization, enabling the state to levy rates and service charges.

Data on urbanisation and informality

The Atlas of Informality argues that data on urbanisation and informality is often inaccurate, incomplete or obsolete.37 This is well illustrated in the case of South Africa where there are large gaps in official census data on informality and land ownership. For example, the 2022 census reported that in greater Johannesburg, currently home to 6.3 million people, just 8.1% of all dwellings were informal. However, the City Region Observatory analysed imaging data to determine that informal dwellings comprised 13.4% of the housing stock.38 This illustrates how official data sources may be inaccurate and that these inaccuracies can be harnessed to manufacture ‘good stories’ about policy and programme impacts.

The great titling debate

Conventional land registration systems often struggle to accommodate intricate and dynamic land tenure relationships which exist in the real world. Land registries capture the legal relationships in relation to recorded land parcels. However, they frequently ignore the diverse social, political, and economic relationships that together with legal rights, truly shape land tenure in diverse societies.

The debate on the advantages/disadvantages of titling of properties in informal settlements in the global South has escalated into “a battleground of ideas.”39 Back in the 1980’s the World Bank was already arguing that “titles would bring tenure security, housing improvements and economic benefits, including rental income, capital gains on sale and access to credit.”40 It was Hernando de Soto who brought this debate to a wider public.41 His argument that the formalisation of the informal would combat poverty and stimulate economic development were regarded as the epitome of neoliberal thinking. The notion of property as a bankable commodity was hotly opposed by community activists and academics in different settings. Over time the different positions on titling became “lumped together under the for or against category” in an ever more polarised debate.42

Research findings on the impacts of titling often draw their conclusions on the basis of case studies. It is only through in-depth systematic literature reviews that the broad trends can be determined. Even then these trends risk overriding and distorting contextual particularities.

A recent synthesis of seven African city studies notes that there is broad agreement that tenure security is an essential element for improved conditions in informal settlements. However, it cautions that “options for tenure security are context-specific and related to the location of the land and therefore the scale of contestation related to land values”.43

The assumption that property rights will vest in single family households is often misplaced. Urban realities are much more complex as multiple families may occupy single dwellings while tenants occupy extensions and backyard shacks. The rights of women, particularly those in customary/ unregistered marriages may also be at risk, unless titling processes specifically take their rights into account.

Tenure regularisation can be bureaucratic and expensive. But processes of regularising access to basic services can create de facto property rights. The issue of utility bills in the residents’ names serve to document their presence, and their claims to the portion of serviced land.

However, it is clear that even if their property rights are finally registered, there is no guarantee that owners will record and legally formalise subsequent land transactions. This is often too bureaucratic and expensive for poor households.

Tenure formalisation can also be actively resisted by some informal settlement dwellers. Some may fear rising taxes and gentrification once property rights have been registered. Ironically, the regularisation of tenure may open the way to displacement of poor households and tenants. Vulnerable households may be unable to afford the cost of rates and services associated with regularisation, although this depends on the estimates of property value and the scale at which property rates are set.

Case studies

The short case studies below illustrate the complexities and contestations associated with urban tenure regularisation in two cities in the global South.

Cape Town, South Africa

Urbanisation in South Africa is high – over two thirds of South Africans already live in urban areas, with this expected to rise to 71% by 2030. Following the democratic transition housing policy focused on the provision of subsidised free-standing houses, to which the new owners would obtain title deeds. Most of these houses were located on the urban periphery where land values were lower. This perpetuated what had become known as the ‘apartheid city’, entrenching historical spatial inequalities. Despite the construction of millions of houses South Africa still faces a massive housing backlog. This was recently estimated to be 2.4 million households.44

In this context many people construct shacks to house themselves, or rent to others. There is an active informal property market in which a one-sided form of leasehold operates. Rental terms for rooms and backyard shacks are set by the landlord without negotiation with the tenant.45 During the Covid 19 pandemic many backyard shack dwellers could no longer pay the rent. They were often evicted without legal protection. This in turn led to land occupations and the establishment of new informal settlements as former tenants rehoused themselves.

Originally focused on delivering fully or partially subsidised housing for low-income families, housing policy now prioritises provision of serviced sites and upgrading of informal settlements. There is a renewed official focus on densification through inner city rental, higher-density ownership typologies, and informal small-scale rental.46

Tenure arrangements have long taken a back seat. This is partly because of the inappropriateness of the complex and expensive Deeds Registry system for the vast majority of households with low incomes. By 2011 there were already 900,000 properties constructed in terms of the housing subsidy scheme which had not been issued with title deeds. There remains a backlog in the processing of title deeds. Over one million houses worth an estimated R242 billion are occupied but their ownership is unrecorded.47

Even where title deeds have been issued, many of them have not been updated to incorporate subsequent property transactions. Many households obtaining a dwelling in terms of the subsidy scheme ignored the seven-year moratorium on the sale of the unit, the majority of which were sold informally.

Back in 2007 the National Department of Human Settlements commissioned a mapping of 1,9 million subsidy beneficiaries to determine how many had been issued with title deeds. “The survey found that most people were not staying in the house that had been originally allocated to them and that there was a major disconnect between deeds records and the reality on the ground”.48 Unsurprisingly there has been a fractious national debate on the merits of titling in South Africa.

Informal sales create a massive divergence between the recorded and the actual owners and occupiers. This divergence applies both to houses for which title has been issued and those for which it has not. This situation has huge financial and administrative implications. Rectification of title deeds is expensive and time consuming and given the scale at which it must be conducted is no longer feasible. At the same time the divergence contributes to mounting arrears in the payment of service charges to municipalities. In cases where the original owner has either informally sold the property or has died, substantial backlogs in the payment of service charges have accumulated 49 as the municipality has no record of the new occupiers.

Since 2023 there has been increased attention in the sector on small scale affordable rental development, the provision of serviced sites, and support to micro developers in township areas. Recent years have also seen an increased focus on the provision of social housing, through leveraging of private sector investment. There has also been attempts to introduce inclusionary housing requiring private sector developers to include a level of more ‘affordable’ housing for those on the lower rungs of the formal property market.

The state role in the provision of housing is reported to be shrinking with a rethink of the housing subsidy programme and a focus on enabling public-private partnerships. Some of the country’s larger cities have started preparing new policies and programmes linked to this, to enable the development of small-scale affordable rental accommodation.50

Insights from Langa

Langa is the oldest African township in Cape Town, planned in the 1920’s within a racially segregated city. The township was designed primarily to accommodate migrant workers from rural areas, housed in hostel blocks for single men. Very few black families had rights to remain permanently in the cities. However, some family housing was provided in the township on a state rental basis.

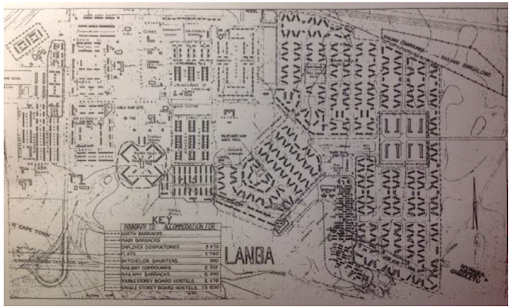

Sketch map of Langa township in 1976 showing hostel types .51

With the collapse of the apartheid state in the late 1980’s, urban influx controls were lifted and Langa was rapidly transformed. This led to deep seated local contestations over space, place and belonging between long-time residents of Langa – the ‘borners’, and migrants with homesteads in the rural areas . At the same time there emerged “a clash of rationalities between techno-managerial and marketised systems of government administration, service provision and planning…and increasingly marginalised urban populations surviving largely under conditions of informality.”52

Family housing previously rented from the state was slowly transferred in ownership. But this frequently resulted in family disputes, as a single name – often that of a man was recorded on the title deed as the owner. This undermined the rights of their partners and other family members, who previously were recognised as having strong claims on the property.

Two Google Earth images below – the first from 2004 and the second from 2011 shows how the township was transformed by a flowering of informality.

Google Earth image of Langa township in 2003 showing Joe Slovo informal settlement and the infill of informal dwellings in the hostel precincts

The Google Earth image above shows how the township became ringed with shacks constructed on every piece of vacant land once state controls on accessing the city were lifted. The spaces in between overcrowded hostel blocks, which now accommodated families were also filled in with shacks. Attempts to upgrade the hostels and convert them to family units led to conflict, as not everyone could find a place in the development.

Google Earth image of Langa township in 2011 showing how parts of Joe Slovo informal settlement are replaced by state subsidised formal housing delivered through the N2 Gateway project.

In the mid 2000’s Langa became the focus of the state driven N2 Gateway housing megaproject. This too was deeply contested, as people were removed from the informal settlement and resettled on the urban periphery to make way for the development. Many people lost access to Langa in the process, as they could not afford the rentals in the social housing units. These in turn became the focus of a rent boycott and today many have seriously deteriorated.

Social housing in Langa has fallen into disrepair. Photo Ashraf Hendriks GroundUp CC-BY-NC-ND. Many of the units have been captured by criminals and have been sublet. The City will not maintain the units unless there is a signed lease with a tenant.

This abridged story of Langa township illustrates the “vast gap that exists between the notion of ‘proper’ communities held by most planners and administrators (grounded in the rationality of Western modernity and development) and the rationality which informs the strategies and tactics of those who are attempting to survive, materially and politically in the harsh environment of Africa’s cities."53

Jakarta, Indonesia

The Land Portal country profile on Indonesia records that it is the fourth most populated country in the world, with over 270 million inhabitants. Its geographical location off mainland Southeast Asia makes the country particularly susceptible to climate disasters. Over 140 million people live on Java, making it the most populous island in the world. The capital city Jakarta is the largest and fastest growing city in Southeast Asia.54

The rapid growth of Jakarta also exposes the fault lines between urban planning and development objectives and the rights of households occupying informal settlements in the city. Urban planning imperatives threaten to displace the poor. They also overwhelm longstanding customary claims to urban land and render vulnerable, even those who have registered their rights in land and received title.

National urbanisation and tenure context in Indonesia

Jakarta's population (over 11 million in 2023) includes large numbers of informal settlements, known as kampungs, or urban villages. Importantly, many kampungs are located on lands where residents have held historical claims. These date back to the period of Dutch colonial rule and were explicitly recognized in post-colonial land legislation.55

Back in 1960, Indonesia passed the Basic Agrarian Law (BAL) which aimed to do away with the dual property rights system inherited from Dutch colonialism. The new law recognised five primary rights: ownership, building, use, cultivation and management.56 However, in practice the BAL is reported to have reinforced a two-tiered system of formal (registered) and informal (unregistered) land rights.57

Tenure in a megacity

Kampungs accounted for 60% of Jakarta’s spatial footprint in the 1960s. However, by 2020 new terminology had been introduced by state planning authorities. This distinguished between kampungs – areas with strong customary claims to land, distinguishing them from slums and irregular housing. In combination these categories covered 42.7% of Jakarta's total land area.58

Within these areas people exercise a range of different property rights. Some have registered and been given title to their properties, but many have been unwilling or unable to register their title. This is in part due to irregularities in the sale and inheritance of kampung land which raises questions about whose rights would be recognised through registration processes, and whose are ignored.59

Many of these densely populated areas lack proper infrastructure and essential services. A 15-year Kampung Improvement Programme (1969-1984) focused primarily on infrastructure development. This gave some upgraded settlements formal recognition within the city, improving integration into the urban fabric. Overall, however, the programme proved to be unsustainable. One explanation was that without registering properties in the upgraded area, the city was unable to collect sufficient tax revenue to continue to fund the programme.60

In 2016 an ambitious land certification programme was launched with the goal of issuing 21 million new land certificates between 2017- 2019. Indonesia already had a massive backlog of land certificates prior to 2016. Issuing a vast number within a short period proved completely unrealistic.

Subsequently there has been a focus on state initiatives to map informal settlements in Jakarta. According to some analysts these initiatives have been used by the state to erode historical rights in land and “provide a mechanism through which the state can assert power to shape the urban space.”61 This delegitimation of de facto land rights has been accompanied by measures to displace informal settlements and evict people as part of “urban revitalisation, greening and flood mitigation measures”. These measures can render titled properties illegal, if for example they were located in a “green zone”, that was now deemed unsuitable for residential use.62

The 2023 spatial plan proposed to set aside 57.23% of high value land currently occupied by irregular settlements “for future “CBD” land uses like office and mixed-use development, trade and services.”63 This suggests that informal settlements will come under increased pressure in the years ahead.

References

[1] KEIL, R. 2017. Suburban planet: Making the world urban from the outside in, John Wiley & Sons.

[2] MERCER, C. 2017. Landscapes of extended ruralisation: postcolonial suburbs in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42, 72-83.

[3] MYERS, G. 2021. Urbanisation in the global South. In: SHACKLETON, C., CILLIERS, S. S., DAVOREN, E. & DU TOIT, M. J. (eds.) Urban ecology on the global South. Springer International Publishing.

[4] SAMPER, J., SHELBY, J. A. & BEHARY, D. 2020. The paradox of informal settlements revealed in an ATLAS of informality: Findings from mapping growth in the most common yet unmapped forms of urbanization. Sustainability, 12, 9510.

[5] MYERS, G. 2021. Urbanisation in the global South. In: SHACKLETON, C., CILLIERS, S. S., DAVOREN, E. & DU TOIT, M. J. (eds.) Urban ecology on the global South. Springer International Publishing.

[6] WATSON, V. 2016. Sustainable Development Goal 11 and the New Urban Agenda: Can planning deliver? : International Society of City and Regional Planners.

[7] Ibid.

[8] GRAHAM, S. & HEALEY, P. 1999. Relational concepts of space and place: Issues for planning theory and practice. European Planning Studies, 7, 623-646.

[9] WATSON, V. 2016. Sustainable Development Goal 11 and the New Urban Agenda: Can planning deliver? : International Society of City and Regional Planners.

[10] SOOD, A. 2019. Speculative urbanism. AM Orum. London: Blackwell.

[11] NOBRE, E. A. C. 2023. Implementing land value capture in a Global South city: evaluation of the experience in the City of São Paulo, Brazil. revista brasileira de estudos urbanos e regionais, 25, e202327. P.9

[12] DYVIK, E., H,. 2024. World population by age and region 2023 [Online]. Statista. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/265759/world-population-by-age-and-region/ [Accessed 15 March 2024].

[13] UNITED NATIONS. 2022. World population prospects: Summary of results. Washington DC.

[14] WORLD BANK. 2023. Migrants, refugees and societies. World Development Report.

[15] SHALAL, A. 2021. Climate change could trigger internal migration of 216 million people - World Bank [Online]. World Economic Forum. Available: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/09/climate-change-could-soon-force-216-million-people-to-leave-their-homes-according-to-a-new-report/ [Accessed 5 March 2024].

[16] BEYER, R. M., SCHEWE, J. & ABEL, G. 2023. Modeling climate migration: dead ends and new avenues. Frontiers in Climate, 5, e1212649.

[17] CLEMENT, V., RIGAUD, K. K., DE SHERBININ, A., JONES, B., ADAMO, S., SCHEWE, J., SADIQ, N. & SHABAHAT, E. 2021. Groundswell part 2: Acting on internal climate migration, World Bank.

[18] AMAKRANE, K., ROSENGAERTNER, S., SIMPSON, N. P., DE SHERBININ, A., LINEKAR, J., HORWOOD, C., JONES, B., COTTIER, F., ADAMO, S. & MILLS, B. 2023. African Shifts: The Africa Climate Mobility Report, Addressing Climate-Forced Migration & Displacement.

[19] BEYER, R. M., SCHEWE, J. & ABEL, G. 2023. Modeling climate migration: dead ends and new avenues. Frontiers in Climate, 5, e1212649.

[20] DE SATGÉ, R. & WATSON, V. 2018. Urban planning in the global South: Conflicting rationalities in contested urban space, Palgrave Macmillan.

[21] HIRSH, H., EIZENBERG, E. & JABAREEN, Y. 2020. A new conceptual framework for understanding displacement: Bridging the gaps in displacement literature between the Global South and the Global North. Journal of Planning Literature, 35, 391-407.

[22] RAPPEPORT, A. 2024. Cities face cutbacks as commercial real estate prices tumble: Lost tax revenues fuel concerns over an 'urban doom loop'. New York Times, [Online].

[23] METH, P., GOODFELLOW, T., TODES, A. & CHARLTON, S. 2021. Conceptualizing African urban peripheries. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 45, 985-1007.

[24] SOOD, A. 2019. Speculative urbanism. AM Orum. London: Blackwell.

[25] PRINCEWILL, N. 2021. Africa’s most populous city is battling floods and rising seas. It may soon be unlivable, experts warn [Online]. CNN. Available: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/08/01/africa/lagos-sinking-floods-climate-change-intl-cmd/index.html [Accessed 29 February 2024].

[26] DE SOTO, H. 2000. The mystery of capital, London, Bantam Press.

[27] TODES, A. & TUROK, I. 2018. Spatial inequalities and policies in South Africa: Place-based or people-centred? Progress in Planning, 123, 1-31.P.2

[28] DENNISON, J. & GEDDES, A. 2021. Thinking Globally about Attitudes to Immigration: Concerns about Social Conflict, Economic Competition and Cultural Threat. The Political Quarterly, 92, 541-551.

[29] BERRY, A. 2020. Anti-immigrant attitudes rise worldwide: poll. Available: https://www.dw.com/en/anti-immigrant-attitudes-rise-worldwide-poll/a-55024481 [Accessed 14 March 2024].

[30] CHARLOT, O., NAIDITCH, C. & VRANCEANU, R. 2024. Smuggling of forced migrants to Europe: a matching model. Journal of Population Economics, 37, 1-29.

[31] DENNISON, J. & GEDDES, A. 2021. Thinking Globally about Attitudes to Immigration: Concerns about Social Conflict, Economic Competition and Cultural Threat. The Political Quarterly, 92, 541-551.

[32] DOKOS, T. 2017. Migration and globalization–forms, patterns and effects. Trilogue Salzburg, 102-114.

[33] IOM. 2024. Missing Migrants Project [Online]. Available: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/ [Accessed 11 March 2024].

[34] UNITED NATIONS. 2024. Remittances In West Africa: Challenges and Opportunities for Economic Development. United Nations Office of the Special Adviser on Africa.

[35] MYERS, G. 2021. Urbanisation in the global South. In: SHACKLETON, C., CILLIERS, S. S., DAVOREN, E. & DU TOIT, M. J. (eds.) Urban ecology on the global South. Springer International Publishing.

[36] LÓPEZ, O. S., BARTOLOMEI, R. S. & LAMBA-NIEVES, D. 2019. Urban Informality: International Trends and Policies to Address Land Tenure and Informal Settlements. Center for a New Economy (CNE), UN HABITAT 2016. Habitat III: Issue paper on informal settlements. Quito.

[37] SAMPER, J., SHELBY, J. A. & BEHARY, D. 2020. The paradox of informal settlements revealed in an ATLAS of informality: Findings from mapping growth in the most common yet unmapped forms of urbanization. Sustainability, 12, 9510.

[38] PATRICK, S. M., HUGO, J., SONNENDECKER, P. & SHIRINDE, J. 2024. A conceptual analysis of the public health-architecture nexus within rapidly developing informal urban contexts. Frontiers in Environmental Science, GÖTZ, G., BALLARD, R., HASSEN, E. K., HAMANN, C., MAHAMUZA, P. & MAREE, G. 2023. Statistical surprises: key results from census 2022 for Gauteng. GCRO Rapid Research Paper. Johannesburg: Gauteng City-Region Observatory.

[39] VARLEY, A. 2017. Property titles and the urban poor: from informality to displacement? Planning Theory & Practice, 18, 385-404.

[40] Ibid.

[41] DE SOTO, H. 2000. The mystery of capital, London, Bantam Press.

[42] VARLEY, A. 2017. Property titles and the urban poor: from informality to displacement? Planning Theory & Practice, 18, 385-404.

[43] OUMA, S., COCCO, D., BELTRAME, D. M. & CHITEKWE-BITI, B. 2024. Informal settlements: Domain report. Working Paper 9. African Cities Research Consortium. The University of Manchester.

[44] CENTRE FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING FINANCE IN AFRICA. 2023. Housing finance in South Africa [Online]. Available: https://housingfinanceafrica.org/countries/south-africa/ [Accessed 18 March 2024].

[45] NGCUKAITOBI, T. 2021. Land matters: South Africa's failed land reforms and the road ahead, Cape Town, Penguin Random House South Africa.

[46] CENTRE FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING FINANCE IN AFRICA. 2023. Housing finance in South Africa [Online]. Available: https://housingfinanceafrica.org/countries/south-africa/ [Accessed 18 March 2024].

[47] Ibid.

[48] SHISAKA DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT SERVICES 2011. Investigation into the delays in issuing title deeds to beneficiaries of housing projects funded by the capital subsidy. Johannesburg: Urban Landmark. P.21 [49] Ibid.

[50] CENTRE FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING FINANCE IN AFRICA. 2023. Housing finance in South Africa [Online]. Available: https://housingfinanceafrica.org/countries/south-africa/ [Accessed 18 March 2024].

[51] SELVAN, D. 1976. Housing conditions for migrant workers in Cape Town 1976. SALDRU Working Paper No. 10. Cape Town: South African Labour and Development Research Unit.

[52] WATSON, V. 2009. Seeing from the South: Refocusing Urban Planning on the Globe's Central Urban Issues. Urban Studies, 44, 2259-2275.

[53] WATSON, V. 2003. Conflicting Rationalities: Implications for Planning Theory and Ethics. Planning Theory and Practice, 4, 395-407.

[54] HAYWARD, D. 2021. Indonesia - Context and land governance [Online]. The Land Portal. Available: https://landportal.org/book/narratives/2021/indonesia [Accessed 18 March 2024], WATSON, V. 2003. Conflicting Rationalities: Implications for Planning Theory and Ethics. Planning Theory and Practice, 4, 395-407.

[55] SHATKIN, G., BRASWELL, T. H. & MARTINUS, M. 2023. Mapping and the politics of informality in Jakarta. Urban Geography, 44, 939-963.

[56] PRAMESTY, A. 2023. Exploring the potential of community land trusts in Jakarta's informal settlements.

[57] SHATKIN, G., BRASWELL, T. H. & MARTINUS, M. 2023. Mapping and the politics of informality in Jakarta. Urban Geography, 44, 939-963.

[58] PRAMESTY, A. 2023. Exploring the potential of community land trusts in Jakarta's informal settlements.

[59] SHATKIN, G., BRASWELL, T. H. & MARTINUS, M. 2023. Mapping and the politics of informality in Jakarta. Urban Geography, 44, 939-963.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

Disclaimer: The data displayed on the Land Portal is provided by third parties indicated as the data source or as the data provider. The Land Portal team is constantly working to ensure the highest possible standard of data quality and accuracy, yet the data is by its nature approximate and will contain some inaccuracies. The data may contain errors introduced by the data provider(s) and/or by the Land Portal team. In addition, this page allows you to compare data from different sources, but not all indicators are necessarily statistically comparable. The Land Portal Foundation (A) expressly disclaims the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any data and (B) shall not be liable for any errors, omissions or other defects in, delays or interruptions in such data, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon. Neither the Land Portal Foundation nor any of its data providers will be liable for any damages relating to your use of the data provided herein.