By Marie Gagné, reviwed by Issa Ousseini, Department of Geography, Abdou Moumouni University of Niamey

This is a translated version of the country profile originally written in French.

At 1,267,000 km², Niger is the largest country in West Africa. However, as two-thirds of its territory lies in the Sahara Desert, farming is only possible in a strip corresponding to the southern third of the country.

Niger is making significant efforts to restore degraded land and soil. Since 2016, the various activities carried out, such as dune fixation and assisted natural regeneration, have made it possible to recover 518 405 hectares.

Photo: Francisco Ortega/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Desertification is a major issue in Niger that mounts pressure on land. Between 1975 and 2016, sandy surface areas increased by 24.8%, reducing forest cover and leading to a loss of soil stability. The degradation of natural resources in the north weakens the pastoral system. In the agropastoral zone in the south, low and erratic rainfall, high temperatures and declining soil fertility also hinder rainfed agriculture. To pursue their activities, farmers in the Sahelian zone increasingly clear forests and encroach on pastoral areas, resulting in recurrent conflicts between farmers and herders.1

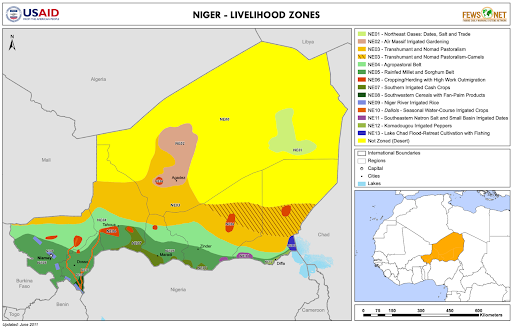

Livelihood zones in Niger, Map prepared by USAID/Fewsnet

Between 1960 and 1990, the contribution of the agricultural, forestry and fisheries sectors to GDP fell drastically, from 75% to 29%. From 1990 onwards, the value added by agriculture began to rise again, reaching 38% of GDP in 2020.2 This percentage is quite high considering the largely desertic character of the country. Most of the agricultural production (87.5%) is devoted to food crops, such as millet, sorghum, rice, cowpeas and maize. This agriculture is mainly rainfed. Although agriculture continues to employ more than 80% of the population, one third of Nigeriens are undernourished.3 The country experienced another drought episode in 2021-2022, resulting in a sharp decline in cereal production and food insecurity for 6.4 million Nigeriens.4

Transhumant and sedentary livestock rearing also play a significant role in the country's economy. Indeed, 87% of the working population is engaged in livestock farming, an activity that contributes to meeting 25% of food needs. This makes Niger the leading exporter of livestock in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).5 Mining is also an important economic sector. Niger's primary exports are uranium, hydrocarbons and gold. Uranium is the country's main source of mineral wealth, but the sector has become less profitable due to the fall in world prices since 2007. Although Niger has a comprehensive body of land legislation, its provisions are, on the whole, weakly enforced and suffer from various shortcomings. As the old laws are no longer adapted to the current context, Niger started to revise its land regulations in 2013.6

Historical context

As Niger is a former French colony in West Africa, the private property regime was introduced in 1932. This regime aimed to formalize ownership through the granting of land titles and established the State as the sole holder of all unregistered land.

At independence, Niger maintained the principle of eminent domain of the state and sought to uphold land registration. Recognizing the legitimacy of customary land rights, the state relied on them and developed procedures to register them. Nevertheless, the government tried to limit the traditional power of land chiefs through the adoption of various laws, including Law No. 62-7 of 12 March 1962, which abolished the privileges acquired over chieftaincy lands. The 1960s were marked by a strong commitment on the part of the State to modernize agriculture and livestock farming.

However, the droughts of the 1970s and a coup d'état in 1974 hampered this dynamic. As a result of the droughts, the population suffered from famine, and the livestock was decimated. In response, the government refocused its national rural development policies on supporting family farms and rebuilding herds to boost food security. In the context of the fight against desertification and the return to democracy, Niger adopted the guiding principles of the Rural Code through Ordinance No. 93-015 of 2 March 1993. In particular, the Ordinance aims at securing land tenure for rural actors, sustainably managing natural resources and ensuring coherent land use planning.7 It defines the principles of orientation, implementation and monitoring of the rural code, which has yet to be drafted, though.

In 2013, a review of Ordinance No. 93-015 highlighted the outdated and contradictory features of different legislative texts on land tenure. Following this assessment, it was agreed to convene a National Consultation on Rural Land Tenure (États généraux sur le Foncier Rural), which took place in 2018 under the aegis of the President of the Republic of Niger. The main recommendation of this event, which gathered over 300 stakeholders from all over the country, was to renew Niger's land policy.

In 2018, the government created a "Technical Committee in charge of leading the process of developing Niger's rural land policy and monitoring the implementation of the recommendations of the National Consultation on Rural Land Tenure." From 2018 to 2020, this Committee organized consultation workshops involving over 1000 people. Customary chiefs, women, youth, farmers, herders, fishermen, civil society representatives, local elected officials and parliamentarians were invited to share their opinions on the content of the policy, which was subsequently presented to the government in 2020.

Given the stakes involved, the adoption of the document was postponed until after the presidential elections in April 2021. Following the election, outgoing President Issoufou Mahamadou handed over power to Mohamed Bazoum. Despite the change in power, the government adopted Niger’s Rural Land Policy on November 9, 2021.8

Land legislation and regulations

The main legislative text governing rural land tenure in Niger remains Ordinance No. 93-015 of 2 March 1993, setting out the guiding principles of the rural code. This ordinance establishes the legal framework for regulating agricultural, forestry and pastoral activities, with a view to drafting a rural code. At the time, the Ordinance was seen as quite innovative, as it reaffirmed the legitimacy of customary land rights in a more operational manner than Law n°61-30 of 19 July 1961 and took more explicitly into account the specific needs of livestock breeders.9 In addition, the Ordinance facilitated rural land registration mechanisms by entrusting management to land commissions in each arrondissement or commune.10

This Ordinance provides that land ownership obtained by virtue of custom enjoys the same protection as that resulting from written law, particularly when it has been registered in the "rural land register" (dossier foncier rural). Owners are expected to develop their land without interruption for more than three years. Failure to develop the land, or to do so sufficiently, does not entail the loss of ownership rights, but does authorize the transfer of land use rights to a third party.11

For its part, the recently adopted Rural Land Policy aims to offer a coherent set of guidelines for sustainable land management, environmental protection, land security for individuals and the state, conflict prevention and rural development. The approach was inspired by the principles and methods developed by the "Voluntary Guidelines (VG) for Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests" and the "Framework and Guidelines on Land Policies in Africa."

Onion harvest in Niger, photo by Remi Nono-Womdim, FAO (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The new policy maintains commune-level land commissions as the body responsible for issuing deeds, while village land commissions certify "the materiality of land rights on the ground." This policy is accompanied by a 2021-2027 Action Plan that includes a strategy for implementing the objectives.

Land tenure classifications

The land tenure system in Niger is divided into 1) the domain of private individuals and 2) the domain of the State and local authorities.

The domain of private individuals concerns residents of Niger, who can secure their land under three systems: customary law, the land register and the rural land register.

Under customary law, land chiefs are involved as witnesses to land transactions and verify that the seller is the true owner. These transactions are sometimes formalized in writing.

The registration of a property in the Land Register confers an individual private property right through the issuance of a land title. The Directorate of State Property and Cadastral Affairs in the Ministry of Finance is responsible for maintaining the Land Register. The government has introduced a simplified procedure for accessing the land title, known as the "sheda" title.12

Ordinance No. 93-015 of 2 March 1993 instituted the rural land register. Besides land titling and registration in the rural register, this ordinance also provides for other mechanisms to formalize land ownership, including the authenticated deed and the private deed. Land commissions are responsible for granting these deeds.

The State has a public domain and a private domain. The public domain of the State or local authorities includes roads, transhumance trails and livestock corridors. Land protected for natural resource conservation also belongs to the public domain of the State or local authorities. Protected lands remain nevertheless accessible to residents for customary pastoral and agricultural uses. Classified forests belong to the public domain of the State. While pastoral grazing is generally allowed in classified forests, agriculture, logging and hunting are prohibited unless a concession with specifications is granted or the land is declassified. Finally, the land undergoing restoration falls within the State's public domain for the duration of the necessary work.

The private domain of the State and local authorities includes reserved land, i.e., strategic reserves for grazing or pastoral development. Land that is vacant or without proof of established ownership also belongs to the private domain of the State.13

Land use trends

Niger is undergoing major land use changes due to the combined effects of population growth, anthropogenic activities and climate change. Pastures and forests are increasingly being converted into agricultural or urban areas.

With the highest birth rate in the world (3.8 per cent per year), demographic growth in Niger is putting considerable pressure on arable lands, especially in the southern zone of the country, where the majority of the population is concentrated and where agricultural and pastoral activities are possible. The population has tripled in 30 years, rising from 8 million in 1990 to 24.2 million in 2020.14

The area devoted to rainfed agriculture at the national level has doubled in forty years. It covered 12.6% of the territory in 1975 compared to 24.5% in 2013.15 During the same period, pastures and livestock corridors consisting of savannahs and steppes lost 15% in size.16

Niger is deploying significant efforts to restore degraded land and soil. Since 2016, the various activities carried out, such as sand dune fixation and assisted natural regeneration, have resulted in the recovery of 518,405 hectares. However, these reforestation efforts (on the order of 7,500 hectares per year) fail to offset the decline in natural forest cover (12,420 hectares per year). It is estimated that Niger's forests have lost 865,300 hectares since 1990, to cover only 1,079,700 hectares in 2020,17 or less than 1% of the territory. Nevertheless, it seems that the rate of desertification is decreasing. According to 2007 data, the desert was advancing by 200,000 hectares per year, whereas this rate lowered to 100,000 hectares in 2020.18

Aïr Mountains and Ténéré Desert in Niger, photography by willemstom, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Land investments and acquisitions

Large-scale land acquisitions in Niger fall into three main categories: agricultural projects, ranches and mining concessions.

In Niger, a significant proportion of agricultural investments are made by local agro-industrial entrepreneurs seeking to acquire land in fertile lowlands and even dune pastures. These acquisitions, which began before the 2000s, involve land that is often already under shared or common use19 and belongs to the public or private domain of the state.

In addition to local business people, foreign companies have attempted to obtain land in Niger. In particular, the proposed acquisition of 120,000 hectares by the Saudi company Al Horaish for Trading & Industry caused a stir in Niger. This public-private partnership targeted pastoral and agricultural land in the Diffa region of southeastern Niger, but it is unclear whether it has materialized.20

In pastoral zones, the creation of vast private ranches has led to the privatization of areas previously used in common. In the department of Abalak alone, for example, three ranches have been set up by 'wealthy commercial herders' with areas ranging from 1,200 to 4,800 hectares,21 or even more,22 violating existing regulations or taking advantage of their shortcomings.

However, it would appear that the presence of land commissions responsible for ascertaining land rights has limited the extent of abusive land acquisitions for the creation of agro-industrial farms or private ranches. In 2014, the government additionally ordered the cancellation of ranch projects under development and the dismantling of ranches already established.23 While these instructions have not been implemented for existing ranches, they appear to have discouraged further expansion.

The mining industry also has significant impacts on rural land in Niger. Uranium mining began in the late 1960s in the desert region of Agadez, in northern Niger. The first site was the Arlit open-pit mine, established in 1968 by French interests and the government of Niger, which is still in production. The Compagnie minière d'Akouta (Cominak), the second-largest uranium mining site in Niger and one of the largest underground mines in the world, started in 1978. In addition to disrupting traditional pastoral systems, the perceived inequitable sharing of mining revenues catalyzed Tuareg rebellions in the 1990s and 2000s. Since then, 15% of mining revenues are assigned to the budget of the communes of the production regions.24

Niger has long been France's primary source of supply for its nuclear power plants, but the sector has been experiencing difficulties since the collapse of uranium prices in 2007. Although a new deposit, the Azelik mine, came into production in 2007, other projects have been put on hold. Cominak also closed in 2021. Although the mine was underground, radioactive tailings that came to the surface contaminated the environment. Uranium's radioactive half-life is estimated at billions of years, resulting in very long-term soil, air and water pollution.25 In addition to uranium mines, there are gold mining sites north of Agadez and in the west of the country (Tillabéri region), as well as oil drilling in the east (Diffa region).

Community land rights

In Niger, traditional chiefs are responsible for land management. As guarantors of customary rights, they play a conciliatory role in resolving land disputes.26 Customary land tenure systems differ from zone to zone. In the agricultural areas of the south, village lands are divided into community lands and family lands. Community land is used collectively by villagers for grazing, gathering, wood harvesting and hunting. By law, it formally falls within the domain of the State, but the State disregards it because it is not surveyed or mapped. Family land is under the authority of the household head.27

The spatial organization of pastoral areas is structured around access to water points. Communities that have built wells, use them regularly or reside nearby have priority rights to water and adjacent pastures. Some transhumant groups without a fixed territory use temporary ponds formed during the rainy season and then turn to wells and boreholes in the dry season. Herders passing through an inhabited area must obtain permission from the owner of the waterhole to water their herd. Traditionally, this permission was granted free of charge or in return for symbolic gifts.28

In Niger, pastoralism is subject to increasing vulnerability. In the Diffa region, for example, surface areas devoted to pastoralism are decreasing due to the expansion of agriculture and a trend towards overgrazing, which depletes fodder resources. The result is heightened competition for access to land and water points between farmers and herders, but also between sedentary and transhumant herders. These pressures, which date back to the 1980s, have been compounded by more recent insecurity caused by the Boko Haram movement. With the rise of this armed group from 2009 onwards, herder families are increasingly subjected to acts of violence or forced to abandon certain grazing areas and change their transhumance itineraries.29 The creation of private ranches also alters regular transhumance routes, leading to overgrazing in the new host areas. In addition, the imposition of fees to access water, a practice that contradicts both custom and law, generates significant costs for transhumant pastoralists and signifies the privatization of space.30

Finally, in the desert areas in the north of the country, oases where fruits and vegetables are grown are dominant. It is estimated that oases cover 2,300 hectares, but this surface area is reportedly decreasing.31 Oases have complex land tenure systems where different rights overlap in the same place, i.e., ownership of the subsoil (i.e., salt resources) is distinct from ownership of agricultural land (for seasonal crops), which is also distinct from ownership of fruit trees (notably palm trees).

Non-formalized customary land rights remain the norm in Niger. Since the creation of the cadastre in 1906, 32,000 land titles have been allocated in Niger, 8,000 of which were between 2005 and 2015,32 or 25% in 10 years. However, the pace of registration appears to be increasing, with an additional 2,000 land titles attributed between 2017 and 2019.33

Overall, the establishment of land commissions has not led to the greater formalization of land rights. Indeed, it is estimated that 20 years after their creation, land commissions have granted administrative deeds for 2% of land in rural areas.34

In total, only 4.5% of the population has "legally authenticated documents for their farmland," such as land titles, operating permits, minutes or sales agreements. Thus, 72.3% of the population holds land, "but has no title or deed of ownership,"35 while 23.2% do not own the land they farm.

Women's land rights

In principle, Niger's legal framework guarantees women the same land rights as men. Article 4 of Ordinance No. 93-15 of 3 March 1993 provides that "rural natural resources are part of the common heritage of the Nation. All Nigeriens have equal access to them without discrimination based on sex or social origin." According to this ordinance, each Land Commission must include a member representing women.36 By introducing an obligation to develop land, the Ordinance also sought to promote access to land for women, young people and descendants of slaves to the detriment of large customary owners who do not cultivate the land themselves.37

Also, the Constitution of 25 November 2010 specifies in article 8 that the Republic of Niger "ensures equality before the law for all without distinction for sex, social origin, race, ethnicity, or religion."38 The National Rural Land Policy adopted in 2021 reaffirms the principle of gender equality in land tenure. It also introduces the possibility for spouses to apply for a deed of land possession or ownership if they have acquired land jointly.39

Village women and their herd in Niger, photo by ILRI/Stevie Mann (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Despite these legal dispositions, it is estimated that in 2014, only 0.3% of women held title to their farmland, compared to 3.6% of men.40 Traditional land tenure thus largely continues to prevail.

Under customary law, men administer the family or lineage's landholdings, composed of both family and individual fields. All family members work in the family fields, whose harvests are managed by the head of the household. Women may have access to individual land, provided by the head of the family. Although women can freely dispose of their harvests, the fields they cultivate belong to the family domain. As such, they cannot make long-term investments in the land (such as sinking wells or planting trees), nor can they sell or rent it.41

With regard to land rights, women in Niger are generally disadvantaged "whether in terms of inheritance, access to good quality land, ownership of plots or participation in land governance." To remedy the situation, the government aims to allocate 35% of state-developed plots to women, youth and people with disabilities.42

Urban Land Tenure

Niger has one of the lowest urbanization rates in Africa (16.43%), behind only Burundi.43 Nevertheless, urban demographic growth is fairly high, at 4.4% per year as of 2020.44 The capital, Niamey, has a population of 1.5 million.

Rural land subdivision and conversion into urban plots represent a major source of revenue for the urban administration. For example, the Niamey Urban Community has massively subdivided land to pay its employees and finance its operations. It has also granted subdivided land to public servants to compensate for salary arrears. However, it is estimated that at least 100,000 parcels of land are left vacant in Niamey. The overproduction of parcelled but unoccupied land creates peri-urban areas characterized by discontinuous inhabited areas and relatively low population density.45

Dromedary in Niamey, Niger, photograph by Gustave Deghilage (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In addition, several spaces belonging to the public and private domains of the State have been parcelled out, sold or illegally occupied. The situation prompted the government to adopt Law No. 2017-20 of 12 April 2017, laying down the fundamental principles of urban planning and development. The Law theoretically prohibited private individuals from carrying out subdivision operations, which became the sole responsibility of the Ministry of Urban Planning and Town Councils.46 However, the new regulation is poorly enforced, as in complicity with the municipalities, subdivisions are carried out under the title of "extensions" of permits already granted by the Ministry.

The percentage of the Nigerien population living in informal settlements or inadequate housing has nevertheless fallen considerably, from 53.1% in 1992 to 10% in 2021. This decline is partly attributable to various government initiatives to promote better access to adequate housing and public infrastructure.47

Land governance innovations

Farmers in the Maradi and Zinder regions of south-central Niger have massively adopted assisted natural regeneration, a simple agroforestry technique that has allowed them to regreen barren lands and better manage soil fertility where fallowing had become impossible. This practice emerged in response to drought episodes (themselves due to declining rainfall from the 1960s onwards), population growth and agricultural expansion. By the mid-1980s, most of the trees in the fields had been felled, subjecting the soil to severe wind erosion. To combat desertification, farmers began to protect the shrubs and bushes that grew spontaneously in their fields. The widespread adoption of assisted natural regeneration has resulted in the restoration of approximately 3 million hectares (30,000 km2 ) of land. The success of this practice is such that the forest cover in the agricultural areas of southern Niger is currently denser than it was 30 years ago, improving soil fertility and increasing the availability of livestock fodder.48

Timeline - milestones in land governance

The 1970s: Major droughts begin in Niger.

1974: A first coup d'état occurs in Niger.

1991: The return to democracy begins.

1993: Presidential elections are organized in March.Niger adopts the Ordinance n°93-015 of March 2, 1993, setting out the guiding principles of the Rural Code.

2010: Niger adopts a pastoral law with Ordinance 2010-029 on pastoralism.

2013: A study is conducted to assess the level of implementation of Ordinance No. 93-015 of March 2, 1993, and the legal and institutional architecture in terms of land tenure.

2017: The government promulgates Law No. 2017-20 of 12 April 2017, laying down the fundamental principles of urban planning and development, repealing Law No. 2013-28 of 12 June 2013.

2018 : A National Consultation on Rural Land (EGFR) is organized under the leadership of the Prime Minister. Following the event, the government sets up a committee to develop a new land policy.

2019: Following several meetings with various government bodies and civil society actors, the committee revises the first draft of Niger's Rural Land Policy Document. This document is then validated during a national workshop.

2021: Mohamed Bazoum wins the presidential election. The Council of Ministers subsequently approves the draft decree on the adoption of the Niger Rural Land Policy and its Action Plan 2021-2027.

Where to go next?

The author's suggestions for further reading.

To learn more about reforestation efforts in Niger under the Great Green Wall, I recommend this short video from Le Monde with AFP. This African Union initiative to restore 100 million hectares of land in the Sahel is beginning to bear fruit in Niger.

If you are interested in women's access to land, I recommend this report by Marthe Diarra and Marie Monimart. The authors describe the contrasting trends in agriculture in the South and the North of the country since the 1990s. In the agricultural areas of the South, land pressure is leading to the eviction of women from their land, resulting in a "defeminization of agriculture." Conversely, on the fringes of agropastoral and pastoral areas in the North, women who have no livestock, or no longer have any, are turning to crop farming. The 'feminization of agriculture' is a response by women from vulnerable households excluded from pastoral activities.

Finally, for an overview of the factors weakening pastoralism and driving conflict, I suggest a report by the FAO. It discusses the impacts of climate change, population growth, modifications in natural resource governance mechanisms and insecurity on pastoral activities.

References

1] Comité Permanent Inter-états de Lutte contre la Sécheresse dans le Sahel (CILSS). 2016. Les Paysages de l'Afrique de l'Ouest : Une Fenêtre sur un Monde en Pleine Évolution. Garretson: U.S. Geological Survey EROS. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101581. https://www.presidence.ne/gographie

[2]https://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicateur/NV.AGR.TOTL.ZS?end=2020&locations=NE&start=1960&view=chart

[3] FAO. 2021. The Voluntary Guidelines: Securing our rights - Niger. Rome. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/voluntary-guidelines-securing-our-rights-niger

[4] Faride Boureima. 2022. « Niger, plus de six millions de personnes seront en insécurité alimentaire ». Studio Kalangou, 16 février. URL : https://landportal.org/node/101618.

[5] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger. Idrissa, Soumana, Soumana Djibo, Boureima Amadou, Seyni Harouna, Somda Jacques, Clarisse Honadia-Kambou, Masumbuko Bora, Davies Jonathan, Ogali Claire, et Onyango Vivian. 2021. Préserver les terres de pâturage et de parcours au Niger. Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN). URL: https://landportal.org/node/101549.

[6] Idé, Fatouma, et Abdoul Aziz Ibrahim. 2021. « Dr. Seydou Abouba, Coordonnateur Du Processus De L’élaboration De La Politique Foncière Au Niger : ‘La gouvernance foncière doit garantir l’accès équitable à tous les Nigériens aux ressources pour pouvoir produire’». Le Sahel, 26 novembre. URL : https://landportal.org/news/2022/01/dr-seydou-abouba-coordonnateur-du-processus-de-l%E2%80%99%C3%A9laboration-de-la-politique-fonci%C3%A8re. République du Niger. 2020. Politique foncière rurale du Niger. URL : https://landportal.org/node/101591.

[7] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger. République du Niger. 2020. Politique foncière rurale du Niger. URL : https://landportal.org/node/101591.

[8] Bazou, Alhou Abey et Idi Leko. 2021. « Zoom sur les processus du foncier rural au Niger ». Bulletin d’information bimestriel de l’Observatoire Régional du Foncier Rural en Afrique de l’Ouest (ORFAO) (1):15-18. URL : https://landportal.org/node/100850. FAO. 2021. The Voluntary Guidelines: securing our rights - Niger. Rome. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/voluntary-guidelines-securing-our-rights-niger Ibrahim, Abdoul-Aziz. 2021. « Lancement de la mise en œuvre de la politique foncière rurale au Niger : Le pays se dote d’un outil adapté au contexte et aux enjeux du moment ». Le Sahel, 11 novembre. URL: https://landportal.org/news/2022/01/lancement-de-la-mise-en-%C5%93uvre-de-la-politique-fonci%C3%A8re-rurale-au-niger. République du Niger. Loi n°61-30 du 19 juillet 1961, fixant la procédure de confirmation et d’expropriation des droits fonciers coutumiers dans la République du Niger. URL : http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/ner167397.pdf.

[9] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger.

[10] République du Niger. Ordonnance n° 93-015 du 2 mars 1993 fixant les principes d'Orientation du Code Rural. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/lex-faoc004660/ordonnance-n%C2%BA-93-015-fixant-les-principes-dorientation-du-code.

[11] République du Niger. Ordonnance n° 93-015 du 2 mars 1993 fixant les principes d'Orientation du Code Rural. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/lex-faoc004660/ordonnance-n%C2%BA-93-015-fixant-les-principes-dorientation-du-code.

[12] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger.

[13] République du Niger. Ordonnance n° 93-015 du 2 mars 1993 fixant les principes d'Orientation du Code Rural. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/lex-faoc004660/ordonnance-n%C2%BA-93-015-fixant-les-principes-dorientation-du-code.

[14] World Bank. 2021. « Country profile : Niger », World Development Indicators. URL : https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=NER.

[15] Comité Permanent Inter-états de Lutte contre la Sécheresse dans le Sahel (CILSS). 2016. Les Paysages de l'Afrique de l'Ouest : Une Fenêtre sur un Monde en Pleine Évolution. Garretson: U.S. Geological Survey EROS. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101581.

[16] Idrissa, Soumana, Soumana Djibo, Boureima Amadou, Seyni Harouna, Somda Jacques, Clarisse Honadia-Kambou, Masumbuko Bora, Davies Jonathan, Ogali Claire, et Onyango Vivian. 2021. Préserver les terres de pâturage et de parcours au Niger. Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN). URL: https://landportal.org/node/101549.

[17] Bokoye, Souleymane. 2020. Évaluation des ressources forestières mondiales. Rapport Niger. Rome: FAO. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/%C3%A9valuation-des-ressources-foresti%C3%A8res-mondiales-2020-rapport-niger.

[18] IRIN. 2007. « Niger: Population surging while farm land is shrinking ». The New Humanitarian. 7 juin. URL : https://reliefweb.int/report/niger/niger-population-surging-while-farm-land-shrinking. Ministère du Plan. 2020. Deuxième rapport national volontaire sur les objectifs de développement durable au Niger. République du Niger. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101460

[19] Hilhorst, Thea, Joost Nelen, and Nata Traoré. 2011. Agrarian change below the radar screen: Rising farmland acquisitions by domestic investors in West Africa. Results from a survey in Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. April. URL: http://www.landgovernance.org/assets/2014/07/Agrarian-change-under-radar-screen_KIT-SNV_aug-upload_0.pdf.

[20] Tchangari, Moussa. 2016. « Bassin du lac Tchad : Les Saoudiens convoitent 120 000 hectares de terres agricoles et pastorales au Niger ». Alternative, 9 juillet. URL : https://landportal.org/fr/blog-post/2021/02/bassin-du-lac-tchad-les-saoudiens-convoitent-120-000-hectares-de-terres-agricoles.

[21] Touré, Oussouby. 2015. À la croisée des chemins. Analyse de l'impact des politiques pastorales sur les éleveurs d’Abalak, Niger. Teddington: Tearfund. URL: https://landportal.org/node/10153.

[22] Thea Hillorst et coll. rapportent le chiffre de 13,200 hectares.

[23] Hilhorst, Thea, Joost Nelen, and Nata Traoré. 2011. Agrarian change below the radar screen: Rising farmland acquisitions by domestic investors in West Africa. Results from a survey in Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. April. URL: http://www.landgovernance.org/assets/2014/07/Agrarian-change-under-radar-screen_KIT-SNV_aug-upload_0.pdf. Touré, Oussouby. 2015. À la croisée des chemins. Analyse de l'impact des politiques pastorales sur les éleveurs d’Abalak, Niger. Teddington: Tearfund. URL: https://learn.tearfund.org/-/media/learn/resources/policy/at-the-crossroads---full-report-march-2015---french.pdf

[24] République du Niger. Loi n°2006-26 du 9 Août 2006 Portant modification de l'Ordonnnace n°93-16 du 02 mars 1993 portant loi minière complétée par l'ordonnance n°99-48 du 5 novembre 1999. URL : http://www.cridecigogne.org/sites/default/files/Niger_Loi_Miniere_2006.pdf.

[25] Jouve, Arnaud. 2021. « Niger: fermeture d’une des plus grandes mines d’uranium. » RFI, 31 mars. URL : https://landportal.org/node/101620.

[26] FAO. 2021. The Voluntary Guidelines: securing our rights - Niger. Rome. URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/voluntary-guidelines-securing-our-rights-niger

[27] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger.

[28] Touré, Oussouby. 2015. À la croisée des chemins. Analyse de l'impact des politiques pastorales sur les éleveurs d’Abalak, Niger. Teddington: Tearfund. URL: https://landportal.org/node/10153.

[29] FAO. 2021. Le Niger – Analyse des conflits liés à la transhumance dans la région de Diffa: Note de synthèse. Rome. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/le-niger-%E2%80%93-analyse-des-conflits-lie%CC%81s-a%CC%80-la-transhumance-dans-la-re%CC%81gion-de-diffa.

[30] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger. Touré, Oussouby. 2015. À la croisée des chemins. Analyse de l'impact des politiques pastorales sur les éleveurs d’Abalak, Niger. Teddington: Tearfund. URL: https://landportal.org/node/10153.

[31] Ghali, Aboubakar. 2016. Étude de la problématique oasienne au Niger. In Gall: Association Almadeina. URL: http://ressources.ingall-niger.org/documents/projets/almadeina/RADDO/Etude/Etude%20probl%C3%A9matique%20oasis.pdf.

[32] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence, and Seyni Souley Yankori. 2015. « Les titres fonciers de plus de 10 ha ». Réseau National des Chambres d'Agriculture du Niger. Note d’information, 1er septembre. URL : https://reca-niger.org/spip.php?article912.

[33] Ministère du Plan. 2020. Deuxième rapport national volontaire sur les objectifs de développement durable au Niger. République du Niger. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101460.

[34] République du Niger. 2020. Politique foncière rurale du Niger. URL : https://landportal.org/node/101591

[35] Ministère du Plan. 2020. Deuxième rapport national volontaire sur les objectifs de développement durable au Niger. République du Niger. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101460.

[36] République du Niger. Ordonnance n° 93-015 du 2 mars 1993 fixant les principes d'Orientation du Code Rural. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/lex-faoc004660/ordonnance-n%C2%BA-93-015-fixant-les-principes-dorientation-du-code.

[37] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger.

[38] Ministère du Plan. 2020. Deuxième rapport national volontaire sur les objectifs de développement durable au Niger. République du Niger. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101460.

[39] République du Niger. 2020. Politique foncière rurale du Niger. URL : https://landportal.org/node/101591.

[40] Ministère du Plan. 2020. Deuxième rapport national volontaire sur les objectifs de développement durable au Niger. République du Niger. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101460.

[41] Bron-Saïdatou, Florence. 2015. La gouvernance foncière au Niger : malgré des acquis, de nombreuses difficultés. Comité technique « Foncier & développement ». URL: https://landportal.org/library/resources/la-gouvernance-foncie%CC%80re-au-niger.

[42] République du Niger. 2020. Politique foncière rurale du Niger. URL : https://landportal.org/node/101591.

[43] https://atlasocio.com/classements/demographie/urbanisation/classement-etats-par-taux-urbanisation-afrique.php

[44] World Bank. 2021. « Country profile : Niger », World Development Indicators. URL : https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=NER.

[45] Meyer, Ursula. 2021. « Interweaving urban land tenure, spatial expansion and political institutions. An urban history of Niamey, Niger. » African Cities Journal 02 (02): 1-20. URL : https://landportal.org/library/resources/interweaving-urban-land-tenure-spatial-expansion-and-political-institutions.

[46] Le Sahel. 2018. « Interview du ministre des Domaines, de l’urbanisme et du logement, Monsieur Waziri Maman : dorénavant, aucun privé ne peut réaliser des lotissements… ils se feront à l’initiative du ministère en charge de l’urbanisme et des mairies ». 5 novembre. URL : https://www.lesahel.org/interview-du-ministre-des-domaines-de-lurbanisme-et-du-logement-monsieur-waziri-maman-dorenavant-aucun-prive-ne-peut-realiser-des-lotissements-ils-se-feront-a-l/.

[47] Ministère du Plan. 2020. Deuxième rapport national volontaire sur les objectifs de développement durable au Niger. République du Niger. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101460.

[48] Comité Permanent Inter-états de Lutte contre la Sécheresse dans le Sahel (CILSS). 2016. Les Paysages de l'Afrique de l'Ouest : Une Fenêtre sur un Monde en Pleine Évolution. Garretson: U.S. Geological Survey EROS. URL: https://landportal.org/node/101581.

Authored on

23 August 2022